Art & Culture

India’s colonial past revealed through 200 masterful paintings

Founded in 1600 as a trading enterprise, the English East India company gradually transformed into a colonial power.

By the late 18th Century, as it tightened its grip on India, company officials began commissioning Indian artists – many formerly employed by the Mughals – to create striking visual records of the land they were now ruling.

A Treasury of Life: Indian Company Paintings, c. 1790 to 1835, an ongoing show in the Indian capital put together by Delhi Art Gallery (DAG), features over 200 works that once lay on the margins of mainstream art history. It is India’s largest exhibition of company paintings, highlighting their rich diversity and the skill of Indian artists.

Painted by largely unnamed artists, these paintings covered a wide range of subjects, but mainly fall into three categories: natural history, like botanical studies; architecture, including monuments and scenic views of towns and landscapes; and Indian manners and customs.

“The focus on these three subject areas reflects European engagements with their Indian environment in an attempt to come to terms with all that was unfamiliar to Western eyes,” says Giles Tillotson of DAG, who curated the show.

“Europeans living in India were delighted to encounter flora and fauna that were new to them, and ancient buildings in exotic styles. They met – or at least observed – multitudes of people whose dress and habits were strange but – as they began to discern – were linked to stream of religious belief and social practice.”

Beyond natural history, India’s architectural heritage captivated European visitors.

Before photography, paintings were the best way to document travels, and iconic Mughal monuments became prime subjects. Patrons soon turned to skilled local artists.

Beyond the Taj Mahal, popular subjects included Agra Fort, Jama Masjid, Buland Darwaza, Sheikh Salim Chishti’s tomb at Fatehpur Sikri (above), and Delhi’s Qutub Minar and Humayun’s Tomb.

The once-obscure and long-anonymous Indian artist Sita Ram, who painted the tomb, was one of them.

From June 1814 to early October 1815, Sita Ram travelled extensively with Francis Rawdon, also known as the Marquess of Hastings, who had been appointed as the governor general in India in 1813 and held the position for a decade. (He is not to be confused with Warren Hastings, who served as India’s first governor general much earlier.)

The largest group in this collection is a set of botanical watercolours, likely from Murshidabad or Maidapur (in present-day West Bengal).

While Murshidabad was the Nawab of Bengal’s capital, the East India Company operated there. In the late 18th century, nearby Maidapur briefly served as a British base before Calcutta’s (now Kolkata) rise eclipsed it.

Originally part of the Louisa Parlby Album – named after the British woman who compiled it while her husband, Colonel James Parlby, served in Bengal – the works likely date to the late 18th Century, before Louisa’s return to Britain in 1801.

“The plants represented in the paintings are likely quite illustrative of what could be found growing in both the well-appointed gardens as well as the more marginal spaces of common greens, waysides and fields in the Murshidabad area during the late eighteenth century,” writes Nicolas Roth of Harvard University.

“These are familiar plants, domestic and domesticated, which helped constitute local life worlds and systems of meaning, even as European patrons may have seen them mainly as exotica to be collected.”

Another painting from the collection is of a temple procession showing a Shiva statue on an ornate platform carried by men, flanked by Brahmins and trumpeters.

At the front, dancers with sticks perform under a temporary gateway, while holy water is poured on them from above.

Labeled Ouricaty Tirounal, it depicts a ritual from Thirunallar temple in Karaikal in southern India, capturing a rare moment from a 200-year-old tradition.

By the late 18th Century, company paintings had become true collaborations between European patrons and Indian artists.

Art historian Mildred Archer called them a “fascinating record of Indian social life,” blending the fine detail of Mughal miniatures with European realism and perspective.

Regional styles added richness – Tanjore artists, for example, depicted people of various castes, shown with tools of their trade. These albums captured a range of professions – nautch girls, judges, sepoys, toddy tappers, and snake charmers.

“They catered to British curiosity while satisfying European audience’s fascination with the ‘exoticism’ of Indian life,” says Kanupriya Sharma of DAG.

Most studies of company painting focus on British patronage, but in south India, the French were commissioning Indian artists as early as 1727.

A striking example is a set of 48 paintings from Pondicherry – uniform in size and style – showing the kind of work French collectors sought by 1800.

One painting (above) shows 10 men in hats and loincloths rowing through surf. A French caption calls them nageurs (swimmers) and the boat a chilingue.

Among the standout images are two vivid scenes by an artist known as B, depicting boatmen navigating the rough Coromandel coast in stitched-plank rowboats.

With no safe harbours near Madras or Pondicherry, these skilled oarsmen were vital to European trade, ferrying goods and people through dangerous surf between anchored ships and the shore.

Company paintings often featured natural history studies, portraying birds, animals, and plants – especially from private menageries.

As seen in the DAG show, these subjects are typically shown life-size against plain white backgrounds, with minimal surroundings – just the occasional patch of grass. The focus remains firmly on the species itself.

Ashish Anand, CEO of DAG, says the the latest show proposes company paintings as the “starting point of Indian modernism”.

Anand says this “was the moment when Indian artists who had trained in courtly ateliers first moved outside the court (and the temple) to work for new patrons”.

“The agendas of those patrons were not tied up with courtly or religious concerns; they were founded on scientific enquiry and observation,” he says.

“Never mind that the patrons were foreigners. What should strike us now is how Indian artists responded to their demands, creating entirely new templates of Indian art.”

Taken From BBC News

Art & Culture

‘There’s no other poem like it’: Why this Robert Burns classic is a masterpiece

Tam O’Shanter is a rip-roaring tale of witches and alcohol, but it has hidden depths. On Burns Night this Sunday – and 235 years after the poem was published in 1791 – Scots everywhere may well be treated to a masterwork with a unique, universal appeal.

If you’re Scottish, or if you wish you were, then this Sunday is a red-letter day. Scotland’s greatest poet, Robert Burns, was born on 25 January 1759, and Burns Suppers are now held every year, all over the world, to mark his birthday. The guests drink whisky (not “whiskey”, please – that’s the Irish and US spelling), they eat haggis, tatties and neeps (don’t ask), and they hear some of the bard’s many ballads and poems. Ae Fond Kiss, To A Mouse and Auld Lang Syne are usually on the bill. And somebody may well recite Tam O’Shanter, a rip-roaring yarn about witchcraft and heavy drinking that was first published 235 years ago in 1791. It’s a poem that has even more to it than most Burns Supper regulars might realise.

“Tam O’Shanter is Burns’s masterpiece, it really is,” says Pauline Mackay, professor of Robert Burns studies and cultural heritage at the University of Glasgow. “It’s one of his most popular works, so when you say it’s your favourite Burns poem, people say, ‘Urgh, that’s so obvious’. But actually, I’ve been studying it for many, many years, and it’s so multifaceted. Burns brought all of his considerable talents to bear on capturing what inspires him, what motivates him, and his own perception of humanity and human nature.”

And that’s not all. Robert Irvine, the editor of Burns: Selected Poems and Songs, notes that there is a darkness to the poem that goes beyond its spine-tingling descriptions of the devil and his minions. “There’s some weird stuff going on there,” he says.

Most of the revellers are ‘rigwoodie hags’, but one witch, Nannie, is young, attractive and scantily clad

The poem tells the mock-heroic tale of Tam O’Shanter, a farmer who spends as much time drinking as he does working. At the end of one market day in Ayr, he retires to the pub with his “ancient, trusty, drouthy crony” Souter Johnnie (ie, Johnnie the shoemaker), never mind that his wife Kate is waiting at home. It’s only after hours of boozing and flirting with the landlady that Tam finally sets off on his horse, Maggie. But it’s a dark and stormy night, so he has to hold on to his hat, and sing songs to keep up his spirits. “Whiles holding fast his gude blue bonnet; / Whiles crooning o’er some auld Scots sonnet.” This reference to a “blue bonnet”, incidentally, is why beret-like flat hats with pom-poms are called Tam O’Shanters.

When he approaches Alloway’s Auld Kirk, Tam notices that a diabolical party is underway inside: witches and warlocks are dancing, and the devil himself, Auld Nick, is playing the bagpipes. Most of the revellers are “rigwoodie hags”, but one witch, Nannie, is so young, attractive and scantily clad that Tam yells out the only words he speaks in the poem: “Weel done, Cutty-sark!” This cat call would later lend its name to the Cutty Sark, a 19th-Century clipper ship that can be visited in Greenwich, London. Roughly translated, it means: “Well done, Short Dress!”

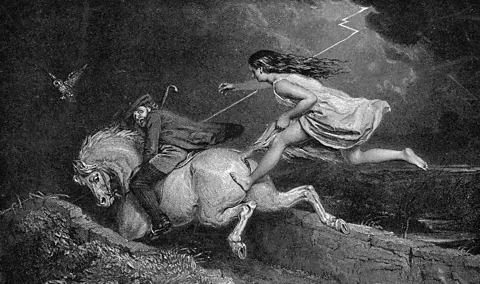

Nannie and her cohorts aren’t pleased to hear it: Tam has to flee on horseback with a crowd of screeching witches in hot pursuit, “Wi’ mony an eldritch skriech and hollo”. Luckily for him, witches can’t cross running water, and the River Doon is nearby. Tam manages to race over the bridge to safety, but Maggie the horse isn’t quite so fortunate. Nannie grabs hold of her tail just as she steps on to the Brig O’ Doon, and – spoiler alert – she is left with “scarce a stump”.

Rude jokes and chilling imagery

Carruthers calls it a “fairly hackneyed ghost story plot”, but the way Burns tells his story means that “there’s no other poem like it in Scottish literature”. Tam O’Shanter is “incredibly rich, so visual, so carefully crafted and so well-paced”, Mackay tells the BBC. “There’s just so much in there: everything from the way Burns has absorbed and assimilated the landscape and folklore of Ayrshire where he was born, and Dumfriesshire where he was writing the poem, to his keen interest in the supernatural, to the various comments that he makes on the complexities of human relationships and gender. All of this is so fascinating.”

There are lines in Scots, and others in English. There are rude jokes, and there is chillingly macabre imagery. There are tributes to the joys of getting drunk with friends in a cosy pub: “Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious. / O’er a’ the ills o’ life victorious!” And there are rueful philosophical musings on how transient those joys are: “But pleasures are like poppies spread, / You seize the flower, its bloom is shed.” Sometimes the narrator will address Tam himself: “O Tam, hadst thou but been sae wise, / As ta’en thou ain wife Kate’s advice!” At other times, he will address another character or the reader / listener – one reason, says Irvine, why the poem “lends itself to performance”, and has become a Burns Supper staple.

In fact, there isn’t much that Burns doesn’t do in Tam O’Shanter – and he does it all in rhyming iambic tetrameter. “He’s showing off,” says Irvine. “He’s doing one thing, and saying ‘Hey, look, I can do this other thing as well.’ In his first volume of poems, he does that between one poem and the next. He adopts different verse genres, he switches from Scots to English, he borrows from all sorts of different traditions – both what we think of now as the folk tradition, and the literary traditions of England and Scotland. It’s a virtuoso display of all the different things that he can do. And in Tam O’Shanter, he’s doing all that within one poem.”

Appropriately for a Burns Supper centrepiece, Tam O’Shanter is a feast, its most satisfying ingredient being its fond and insightful portrait of a character described as “the universal everyman” by Prof Gerard Carruthers, the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Robert Burns. Burns is admired for his egalitarian politics, and even in his rollicking horror comedy, his sympathy for the common man shines through. “Tam O’Shanter is a poem of misdirection,” Carruthers tells the BBC. “Burns is saying: ‘Look at this! Look at the witch! Look at the horse!’ Whereas in fact the real thing that he is talking about is the way in which we’re incorrigible as human beings.” The poem glows with “ridicule and affection at the same time for Tam, and by extension for the human psyche in general”.

It’s a poem about humanity – the pleasures and the appetites, the challenges and the frailties – Gerard Carruthers

Burns – a notorious womaniser – is especially sharp on masculine foibles. “Burns knows the male mind,” says Carruthers. “He knows that men in a lot of ways are stupid wee boys.” On the other hand, says Mackay, women may recognise themselves in Tam O’Shanter, too. “It’s a poem about humanity – the pleasures and the appetites, the challenges and the frailties – and I think that’s one of the reasons why Burns is so universally popular. He talks about what it is to be a human being – and everything that we see in different places throughout his poetic oeuvre is somehow represented in this one poem.”

Still, alongside its compassion, there is devilry of more than one kind in Tam O’Shanter. “The weird and disturbing thing about this poem is that Burns’s father, William Burnes, was a very pious and serious man who despaired of the libertine tendencies of his son,” says Irvine. “He organised repairs to Alloway Kirk when Burns and his brother were boys, and one of the reasons for that is that he wanted to be buried there – and he was. So, in 1784 Burns’s father was buried in Alloway churchyard, which Burns then makes famous as the site of a witches’ orgy. Was he getting revenge on his father for his disapproval of his eldest son?”

As well as everything else Burns is doing in Tam O’Shanter, it could be argued that he is almost literally dancing on his father’s grave. Anyone who hears it at a Burns Supper on Sunday will have plenty to chew on.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Art & Culture

Archaeological Seminar on Indus Valley Civilization of Pakistan in France

Paris ( Imran Y. CHOUDHRY):- The Embassy of Pakistan organized an event on the archeological studies of the 5000-year-old Indus Valley Civilization with Dr. Aurore Didier, Director of the French Archaeological Mission of the Indus Bassin.

Representatives of the UNESCO World Heritage Center, the Agha Khan Development Network (AKDN), archaeologists, historians and diplomats attended the event, which was organized with the support of the “Cercle des Amis du Pakistan”.

Dr. Didier briefed the audience on the history of the archeological excavations carried out by French archeologists in Pakistan. She gave an update on the latest research resulting from ten years of excavations at Chanhu-daro, one of the emblematic sites of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization. She also addressed how the adaptation of ancient populations to river and environmental fluctuations can be a key to understanding the current crises related to climate change and natural disasters that heavily impact South Asia today.

Addressing the audience, Ambassador Mumtaz Zahra Baloch noted the seventy years of cooperation between Pakistan and France in the domain of archeology. She appreciated the contributions made by the French Archeological Mission in Pakistan in research on the Indus Valley Civilization; and in promoting knowledge and competencies amongst local communities and scholars.

The Ambassador also reiterated her warm support for the “Cercle des Amis du Pakistan” for its initiatives in highlighting the cultural richness and diversity of Pakistan.

Art & Culture

From Bank Lines to Bus Seats: Bold Lessons in Courtesy, Courage, and Everyday Survival

In the line of bill payers at the bank,

As the fairer sex,

If sick, don’t just be blank

“Ladies first”, “excuse me11, “before you please.”

For deals with unpaid bills,

Ask for goods back, threat if you will,

Repeat the request for a job.

You may make it from the mob,

Instead of standing, share the seat on the bus

Isn’t it much better than making a fuss,

Whatever you do during tug-of-war, do not push the rope

Or you’ll be the laughing stock amidst cries of, “What a dope.”

-

Europe News11 months ago

Europe News11 months agoChaos and unproven theories surround Tates’ release from Romania

-

American News11 months ago

American News11 months agoTrump Expels Zelensky from the White House

-

American News11 months ago

American News11 months agoTrump expands exemptions from Canada and Mexico tariffs

-

American News11 months ago

American News11 months agoZelensky bruised but upbeat after diplomatic whirlwind

-

Art & Culture11 months ago

Art & Culture11 months agoThe Indian film showing the bride’s ‘humiliation’ in arranged marriage

-

Art & Culture11 months ago

Art & Culture11 months agoInternational Agriculture Exhibition held in Paris

-

Pakistan News7 months ago

Pakistan News7 months agoComprehensive Analysis Report-The Faranian National Conference on Maritime Affairs-By Kashif Firaz Ahmed

-

Politics11 months ago

Politics11 months agoUS cuts send South Africa’s HIV treatment ‘off a cliff’