China

China’s Edge and America’s Fragility

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY) :- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : When a member of Congress asked who now holds the advantage between the United States and China, Kurt M. Campbell did not search for diplomatic shelter. He answered plainly—“China, China, China”—and added that America is in a more fragile position. That exchange distilled a wider realization in Washington: the contest is no longer about who has the cleverest idea, but about who can pair ideas with scale, speed, finance, and supply chains that actually deliver.

Across robotics, autonomous systems, shipbuilding, critical minerals, and the green-energy stack, China has assembled an industrial machine that converts plans into production with few seams. The United States still leads in many forms of research and in the highest tiers of AI hardware and software. Yet too often these strengths sit on islands that are hard to connect to the physical economy. China, by contrast, works from the factory outward. It absorbs a technology, replicates it at home, pushes costs down, and then ships it to the world. That pattern—learn, scale, export—now runs through much of its economy.

This is evident on factory floors. China has built the world’s largest base of industrial robots and the domestic suppliers to keep adding more of them, allowing factories to iterate quickly and standardize quality. It shows up in the air as well, where Chinese drones dominate civilian markets and where military variants have spread to buyers that find Western systems unaffordable or unavailable. Autonomy at scale is not just a technical feat; it is a logistics and training advantage that compounds year after year.

The imbalance is even clearer at sea. Chinese yards deliver commercial ships at a rate that American yards cannot currently approach. Those deliveries are not only commercial statistics. They translate into maritime resilience, sealift, and the capacity to replace hulls fast if a crisis damages them. Industrial power is not an abstraction; it is a queue of vessels sliding down the ways, month after month. America’s shipbuilding base, meanwhile, is thin, specialized, and expensive to expand, which leaves the country reliant on time it may not have.

Beneath these visible platforms lies a quieter source of leverage: rare earths and allied magnet materials. Modern electronics, precision weapons, wind turbines, and electric drivetrains all depend on them. China does not merely mine a large share of these inputs; it processes and refines them, and it manufactures the magnets that sit at the end of the chain. When Beijing tightened export restrictions, markets felt the tremor immediately. U.S. officials have pressed China to ease those curbs and have worked to rally partners to reduce concentration risk. That effort is prudent, but it also acknowledges the present reality—critical stages of the chain are outside American control.

It is here that the familiar American toolkit—tariffs, export controls, and the weaponization of data and finance—meets its limit. Measures of this kind can unsettle smaller or more fragile economies; they have done so repeatedly in the past. They are far less effective against a state with a continental-scale market, deep foreign-exchange reserves, a disciplined industrial policy, and broad capacity to substitute or reroute flows when pressured. China has spent years preparing for that pressure by localizing essential inputs, building parallel financial pipes, and hardening its digital and data regimes. A country that can supply so much of its own demand and anchor so many others’ supply is not easily forced to change course from the outside.

That is why the question posed in the hearing—will punitive tariffs work this time—lands differently today. Tariffs can raise Chinese costs at the American border, but they also raise costs for American producers who rely on Chinese inputs at every intermediate step. If the response from Beijing is to ratchet controls on minerals, chemicals, or magnet materials, the downstream impact is immediate: delays, higher bills, and quality slippage as firms scramble for substitutes. The economic effect accumulates in quieter ways as well. Investment decisions are deferred; projects are redesigned; factories operate below capacity. The result is slower growth and a steady erosion of credibility in the claim that America can out-produce its rival where it matters most.

Washington sees this bind and is examining ways to mine, process, and manufacture more of these inputs at home. That path is necessary, but it is not quick. Permitting, capex, skilled labor, environmental safeguards, local consent, and shared infrastructure mean any serious build-out takes well over a decade to mature. Even then, the unit costs will be markedly higher than those produced by an ecosystem in China that has already reached enormous scale. The arithmetic is straightforward: if domestic inputs are several times more expensive than imported ones, consumers pay more, manufacturers lose margin, or both. And if China chooses to restrict intermediate goods while America is still scaling its replacements, the squeeze is immediate. It is the classic choice between the devil and the deep sea.

None of this argues for resignation. It argues for realism. Treating China as an equal party in the global economy does not mean conceding strategic ground; it means recognizing that coercive instruments will not deliver quick or clean wins. A better first step is to lower the temperature of the tariff war by restoring duties toward earlier baselines and by limiting new restrictions to genuinely narrow security cases with clear, auditable justifications. That would not end competition. It would simply replace a spiral of retaliation with rules that both sides can plan around, which is the precondition for any serious industrial strategy at home.

De-escalation abroad must be matched by seriousness at home. The United States needs a long-horizon, bipartisan program that outlasts election cycles and that treats production as a national capability, not a slogan. That means modernizing ports and shipyards so output can compound rather than stall; accelerating permitting without waiving environmental standards; building regional hubs for magnets, specialty chemicals, and advanced components with public-private risk sharing; aligning procurement with delivery so firms are paid to produce, not to promise; and investing in workforce pipelines that can staff mines, mills, fabs, and yards. Recycling and re-use should be embedded from the start so domestic supply is not only larger but also more resilient when prices swing.

The same principle should guide the data front. The United States can and should protect sensitive datasets and core algorithms, but it should avoid broad regimes that punish neutral commercial activity or force partners to choose camps. A narrower, predictably enforced set of rules will better protect security without undermining competitiveness. Data is valuable because it flows; policy that freezes it indiscriminately tends to reduce American firms’ reach more than it constrains China’s.

Some will hear this and worry that stepping back from the tariff cliff signals weakness. The opposite is true. It signals confidence that America’s real advantage lies in the combination of research excellence, entrepreneurial depth, and an open capital market that can scale new industries when the ground rules are stable. Tariffs and blunt data controls may temporarily bruise a competitor, but they rarely build capacity at home. Capacity is built by patient investment, steady rules, and a clear list of priorities that does not change with each headline.

Campbell’s answer in the hearing was a snapshot of the present, not a verdict on the future. China’s strength today rests on a disciplined link between strategy and production. America’s path back runs through the same link. It will not be achieved by trying to bludgeon a rival that has already insulated itself from the tools that once worked on others. It will be achieved by lowering the noise, rebuilding the sinews of industry, and competing on the only terrain that decides enduring power: the ability to design, build, and deliver at scale. If the United States chooses that course, it will find that fragility is not fate. It is a diagnosis—and like any diagnosis, it is most useful when it prompts the right treatment.

China

Beijing as Europe’s New Geopolitical Mecca

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY) :- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : There was a time, not long ago, when the word “China” in European capitals was spoken in the language of caution, if not suspicion. Parliaments passed laws to block Chinese acquisitions of strategic assets. Regulatory walls were erected against Chinese technology, telecommunications equipment, social media platforms, and even academic cooperation. Brussels and national governments debated how to “de-risk” from Beijing, how to preserve Europe’s cultural, economic, and technological sovereignty from what they framed as an expanding Chinese influence. China was cast as a systemic rival, an adversary whose footprint in Europe had to be contained at almost any cost.

Yet within a single year of Donald Trump’s return to the center of global politics, that posture has undergone a remarkable reversal. What once looked like a coordinated Western front to slow China’s rise has given way to a steady procession of European and North American leaders boarding planes for Beijing. The symbolism is hard to miss. The very capitals that once competed to demonstrate their distance from China are now, one after another, paying homage to the Chinese leadership, signing strategic agreements, and speaking the language of partnership rather than containment.

The shift did not begin in Beijing. It began in Washington. Trump’s posture toward Europe and America’s traditional allies has been unmistakably transactional and, at times, openly coercive. His handling of the Ukraine war, his pressure on European governments to accept a U.S.-designed “peace plan” that many in Europe saw as conceding too much to Russia, and his blunt warning that allies who did not fall in line would face punitive trade measures, all sent a shockwave through the Atlantic alliance. When European leaders drew a red line over Greenland—declaring it non-negotiable and off-limits to any form of geopolitical bargaining—Trump’s response, threatening sweeping tariffs against those who opposed him, was read not as negotiation but as arm-twisting.

For Europe, this was a wake-up call. The assumption that the United States, regardless of who occupied the White House, would remain a predictable anchor of stability and partnership began to look fragile. The message many leaders took from Washington was stark: past cooperation, shared history, and alliance commitments would not necessarily shield them from economic or political punishment if their national interests diverged from those of the United States.

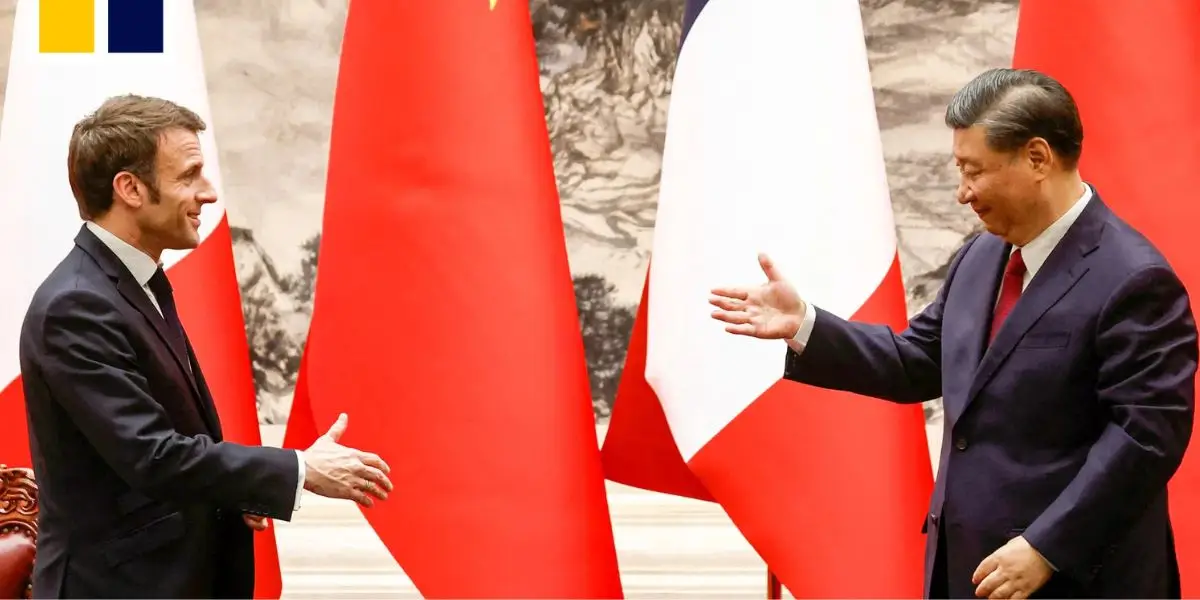

It is against this backdrop that the “pilgrimage” to China must be understood. The first high-profile visit, after years of diplomatic coolness, came from France’s president. His trip to Beijing, the first in nearly a decade, signaled that Europe’s second-largest economy was prepared to reopen channels not just for trade, but for strategic dialogue. Soon after, Canada’s prime minister followed suit, making his own journey to China after years of strained relations. Now, Germany’s chancellor is preparing to land in Beijing, with a delegation heavy on industry, energy, and technology leaders in tow. Behind them, other European heads of government are lining up, each seeking their own audience, their own agreements, their own place in what increasingly looks like a re-centered global economy.

The substance of these visits goes far beyond ceremonial handshakes. Agreements are being signed across a broad spectrum: renewable energy, solar and wind projects, electric vehicles, advanced manufacturing, artificial intelligence, infrastructure financing, and technology transfer. In some cases, even defense cooperation and strategic dialogue are quietly being placed on the agenda. The tone is pragmatic, even eager. Where once European leaders warned of dependence on China, they now speak of “win-win” frameworks, of diversification, of building parallel channels of growth and security that do not run exclusively through Washington.

China, for its part, has played the role of the patient host. Chinese leaders have emphasized humility, mutual respect, and the search for common ground. The rhetoric is carefully calibrated: no lectures on internal politics, no overt demands for ideological alignment, but a steady emphasis on economic opportunity, infrastructure development, and long-term partnership. For European and Canadian leaders bruised by what they perceive as Washington’s heavy-handedness, the contrast is striking.

This realignment is not confined to Europe. Across the Caribbean and parts of the Western Hemisphere, governments are also reassessing their strategic options. Countries long accustomed to living in the shadow of U.S. power—economically, diplomatically, and sometimes militarily—are watching Europe’s pivot with interest. The lesson many are drawing is that diversification is no longer a luxury; it is a necessity in a world where economic pressure and sanctions have become routine tools of statecraft.

Nowhere is this broader shift more visible than in the Middle East, particularly in the evolving standoff between the United States, Israel, and Iran. European governments have shown a marked reluctance to back any new American or Israeli military adventure in the region. When U.S. naval forces moved closer to Iranian waters, signaling readiness for confrontation, European capitals responded not with public endorsements but with calls for restraint and diplomacy.

At the same time, China and Russia have deepened their engagement with Tehran. During recent periods of heightened tension, both powers offered diplomatic cover and, according to many analysts, strategic support that helped Iran withstand external pressure. The result has been a recalibration of power. Iran now presents itself not as an isolated state under siege, but as a node in a broader Eurasian network, backed by two permanent members of the UN Security Council and enjoying at least tacit sympathy from much of the Global South.

For Europe, this matters. The continent’s leaders are acutely aware that a new war in the Middle East would have direct consequences for energy prices, migration flows, and internal political stability. Aligning unquestioningly with Washington and Tel Aviv in such a scenario risks not only domestic backlash but also the loss of diplomatic leverage with Beijing, Moscow, and a large swath of the Muslim world. By contrast, maintaining open channels with China offers Europe a potential role as a mediator, or at least as an independent actor rather than a subordinate ally.

Critics in Washington see Europe’s turn toward Beijing as naïve, even dangerous. They warn of hidden dependencies, of technology transfers that could erode Western security, of economic ties that might one day be weaponized. European leaders counter that the greater danger lies in strategic monoculture—placing all economic, political, and security eggs in a single basket that may no longer be as reliable as it once was.

The symbolism of these Beijing visits has been amplified by their timing. As European leaders walk the red carpets of the Great Hall of the People, Trump prepares to host—or confront—some of them in Washington. The contrast is deliberate. The message, implicit if not explicit, is that Europe will not be treated as a collection of smaller states to be disciplined through tariffs and threats. It is a bloc of 450 million people, a major economic and technological power in its own right, and it intends to act like one.

The broader narrative taking shape is almost poetic in its irony. The United States, long the architect and champion of a liberal international order built on open markets, alliances, and multilateral institutions, is now seen by many as retreating into a more unilateral, interest-driven posture. China, once portrayed as the outsider challenging that order, is positioning itself as a pillar of stability, investment, and predictable partnership.

Whether this role reversal will endure is an open question. Europe’s ties to the United States remain deep, woven through NATO, financial systems, and decades of political and cultural exchange. But something fundamental has shifted in the psychology of European leadership. The assumption of automatic alignment has given way to strategic hedging.

In this unfolding story, the “geopolitical train” metaphor resonates. Many in Europe believe that the momentum of global growth, infrastructure development, and technological innovation is increasingly centered in Asia, with China as a primary engine. To miss that train, they fear, is to risk long-term economic stagnation and strategic irrelevance.

For Washington and Tel Aviv, the picture looks more uncertain. Their ability to mobilize broad international coalitions around security initiatives—particularly those involving Iran—appears diminished. Even traditional partners are choosing caution over commitment, dialogue over endorsement.

History will judge whether this moment marks a temporary detour or a lasting change of direction. What is clear is that, in the span of a single year, the diplomatic map of Europe and its transatlantic relationship has been redrawn in ways few would have predicted. The pilgrimages to Beijing are not merely about trade deals or investment packages. They are a statement of intent—a declaration that in a world of shifting power, Europe intends to keep its options open, its partnerships diverse, and its future unbound to the will of any single capital, however powerful.

China

How Trump Pushed the World Toward Beijing

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY) :- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : There are moments in history when power does not merely shift—it exposes itself. The first year of Donald Trump’s second term has become such a moment, not because it introduced entirely new instruments of American statecraft, but because it redirected the same tools of pressure, coercion, and economic weaponization that the United States once reserved for weaker or dependent nations toward its own traditional allies. In doing so, Washington did not just shock the global system; it fractured it, driving country after country—by calculation, necessity, or defiance—into the strategic and economic orbit of China.

For decades, the United States shaped the political and financial architecture of much of the developing world through a familiar mechanism: military reach, dollar dominance, and institutional leverage over global bodies such as the IMF and World Bank. Countries in South Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, Eastern Europe, and parts of Africa learned to live within a system where access to capital, trade, and even political legitimacy could be expanded or constricted at Washington’s discretion. Many endured in silence, not because they agreed, but because they lacked the economic or military weight to resist.

What changed in this era is not the method, but the target. The same logic of tariffs, sanctions, threats, and strategic intimidation was applied to nations that had long believed themselves protected by alliance and shared identity. Canada, Europe, and the wider Western hemisphere were confronted not as partners, but as economic adversaries and strategic liabilities. This reversal carried a powerful message: loyalty offered no immunity.

Canada’s experience became a defining case study. Accusations of economic exploitation, sweeping tariff threats, and rhetoric that questioned Canada’s sovereignty struck at the heart of a relationship built on the world’s deepest bilateral trade integration. For Ottawa, the conclusion was stark. Dependency on a single market had become a strategic risk. The response was not submission, but diversification. Trade corridors were widened toward the European Union through CETA, expanded across the Asia-Pacific via the CPTPP, and recalibrated toward energy and investment ties with the Gulf and Asia. China, as the world’s largest trading nation, inevitably became central to this recalibration—not by ideological alignment, but by economic gravity.

Europe’s pivot followed a parallel but more consequential path. The dispute over Greenland, framed by Washington as a strategic necessity for missile defense and Arctic dominance, was read in European capitals as a unilateral assertion of power that disregarded sovereignty and alliance consultation. The European Union, often divided on policy, responded with rare cohesion. The rejection of American demands was not merely territorial—it was systemic. It reflected a growing determination to insulate Europe’s political and economic future from what it increasingly viewed as unpredictable American pressure.

This shift soon extended into the financial realm. European policymakers began openly discussing the risks of overexposure to U.S. Treasury holdings and the vulnerability created by dollar-dominated trade and settlement systems. This trend has taken on new political meaning in an environment where financial access is increasingly treated as a strategic weapon.

At the same time, the BRICS bloc—now expanded to include major energy producers and regional powers—has accelerated efforts to build alternative mechanisms for trade settlement, development finance, and cross-border investment that bypass traditional Western-controlled institutions. Local-currency trade arrangements, new development banks, and parallel payment systems are no longer theoretical exercises; they are active projects driven by a shared desire to reduce vulnerability to American financial leverage.

In this environment, China has not needed to aggressively recruit allies. Its role as the central node of global manufacturing, trade, and infrastructure has done much of the work. With annual trade volumes exceeding $4 trillion and deep supply-chain integration across Asia, Europe, Africa, and Latin America, China has become economically indispensable to much of the world. The Belt and Road Initiative, spanning more than 140 countries, has embedded Chinese capital, logistics, and construction into the physical and economic foundations of entire regions. For many states, disengaging from China is no longer a policy option—it is an economic impossibility.

Europe’s own posture toward Beijing illustrates this reality. Only a few years ago, European policy focused on “de-risking” and restricting Chinese investment in strategic sectors. Today, that posture is being recalibrated at unprecedented speed. High-level dialogues on industrial cooperation, green technology, electric vehicles, and infrastructure investment reflect a recognition that Europe’s economic competitiveness is tied to engagement with China, not isolation from it.

Canada’s recalibration mirrors this logic. Energy partnerships with the Gulf, expanded Asian trade, and financial diversification are not ideological statements; they are strategic hedges against a United States that has signaled its willingness to weaponize economic interdependence.

Across the Global South, the pattern is even more pronounced. Countries in Africa, Central Asia, Latin America, and Southeast Asia—many already deeply embedded in Belt and Road projects—see in this Western fracture a confirmation of their long-held belief that reliance on a single power center is dangerous. For them, China’s appeal lies not in moral claims or ideological alignment, but in scale, speed, and predictability of economic engagement.

This is where the geopolitical landscape takes on its starkest contrast. As China’s economic centrality expands, the United States finds itself increasingly isolated in political terms. In this emerging narrative, only one relationship remains absolute: the United States and Israel, bound together in mutual political and strategic defense as much by global criticism as by shared policy.

Israel, facing growing diplomatic, legal, and public pressure across Europe, the Global South, and even within Western societies, leans heavily on American veto power and political backing in international forums. The United States, in turn, finds itself defending Israel in a world where sympathy and alignment are steadily shifting elsewhere. The result is a form of strategic isolation that contrasts sharply with China’s expanding web of economic partnerships.

The Western hemisphere, once considered America’s natural sphere of influence, now reflects this tension. Caribbean and Latin American states increasingly engage China as a primary trade partner, infrastructure financier, and development lender. In Africa, China has surpassed traditional Western powers in trade volume and project scale. In the Middle East, even long-standing U.S. partners diversify toward Beijing for energy, technology, and investment ties.

What emerges is not a world won by China through conquest or coercion, but one reshaped by America’s own confrontational posture. The paradox of this moment is that America’s political capital is eroding. China, by contrast, often avoids overt military or ideological confrontation, relying instead on the slow, cumulative force of economic integration. The gravitational pull of markets, supply chains, and infrastructure has proven more durable than the shock of tariffs or the threat of sanctions.

In the unfolding order, China’s rise has not been driven solely by its own strategy, but by the vacuum created as the United States confronts rather than consolidates. The world’s capitals, boardrooms, and ministries increasingly calculate their futures not in terms of allegiance, but in terms of access—to markets, to capital, to infrastructure, and to stability. In that calculation, Beijing now sits at the center of the equation.

What history may ultimately record is not merely a contest between two powers, but a transformation in how power itself is measured. Military strength and financial dominance remain formidable, but in a world bound by trade, technology, and shared vulnerability, the ability to attract, integrate, and sustain economic relationships may prove to be the decisive force of the century.

China

How Trump Opened the Polar Door to China

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY) :- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : The Arctic, once a frozen frontier of quiet diplomacy and carefully balanced power, is rapidly becoming a theater of geopolitical drama. What makes this moment striking is not merely China’s growing presence in the polar north, but the pathway that has led it there. In a twist of strategic irony, policies designed in Washington to contain Beijing’s global reach appear to have instead nudged America’s closest allies toward deeper engagement with China—transforming the Arctic into a new symbol of a shifting world order.

For decades, Canada stood as one of the United States’ most dependable partners, sharing not only borders and security arrangements but also a sense of political alignment rooted in NATO, democratic values, and mutual defense. Canadian soldiers fought alongside American forces in distant theaters, reinforcing the idea of a partnership that went beyond transactional interests. Yet recent years have strained that bond, as a sharper, more unilateral American posture has unsettled long-standing assumptions about alliance and trust.

The shockwaves intensified when Washington floated the idea of exerting direct control over Greenland, framing the move as a preemptive step to block Chinese and Russian influence in the Arctic. While cast in the language of strategic necessity, the message that reverberated through Europe and North America was one of disregard for sovereignty and partnership. For Denmark and Greenland, the proposal felt less like an offer of cooperation and more like a declaration of intent, prompting unease across the Nordic region.

Against this backdrop, Canada’s reported openness to involving China in Arctic research and development takes on a deeper meaning. It is not simply about scientific collaboration or icebreaker technology; it signals a recalibration of strategic options. The Arctic’s future hinges on access, infrastructure, and year-round navigability, and in these areas, China has invested heavily. Its growing fleet of icebreakers, polar research stations, and logistical capabilities gives it a practical advantage in a region where technological capacity often matters as much as territorial proximity.

This development forms what some observers describe as a “double pincer” dynamic. On one side, China has cultivated research and commercial ties with Nordic countries under international law and bilateral frameworks. On the other, Canada’s engagement opens a transcontinental corridor of cooperation that links North America’s Arctic access with Europe’s northern gateways. The result is a network that extends China’s influence across the polar circle without the need for direct territorial claims, relying instead on partnership, investment, and technical expertise.

The strategic implications are profound. Climate change is steadily reducing ice coverage, shortening shipping routes between Asia, Europe, and North America by as much as 40 percent. What was once a seasonal passage is edging toward year-round viability, transforming the Arctic into a critical artery for global trade, energy transport, and mineral supply chains. Control over icebreaker fleets, ports, and monitoring systems becomes a form of soft power, shaping who sets the rules for access and security.

China’s Arctic engagement also dovetails with its broader Belt and Road Initiative, which has already linked more than 150 countries through infrastructure, logistics, and digital networks. The extension of this vision into polar waters reframes the initiative as not merely a land-and-sea project, but a planetary one—connecting continents through roads, ports, fiber-optic cables, and now, ice-cleared maritime corridors. For partner countries, the appeal lies in tangible investment and shared development rather than overt military alignment.

Europe’s role in this evolving landscape reflects its own reassessment of transatlantic ties. Leaders in Paris and Berlin have spoken openly about strategic autonomy, emphasizing the need to diversify partnerships in a world where U.S. policy can shift sharply with domestic politics. High-level visits to Beijing and renewed economic engagement signal a willingness to explore avenues of cooperation that Washington has discouraged, particularly in areas like research, energy, and infrastructure.

This recalibration is not driven by ideological conversion to China’s worldview, but by a pragmatic reading of interests. European states, facing energy transitions, supply chain vulnerabilities, and economic competition, see value in maintaining multiple channels of partnership. The Arctic, rich in rare earths, hydrocarbons, and strategic shipping lanes, becomes another arena where diversification seems prudent rather than provocative.

The ripple effects extend beyond the polar north. In the Middle East, China and Russia’s consistent calls for sovereignty and non-intervention have positioned them as counterweights to U.S. influence, particularly in countries wary of regime-change rhetoric. In Latin America, Beijing’s infrastructure financing and trade agreements have offered alternatives to traditional U.S.-centric economic models. Together, these trends paint a picture of a world where influence is increasingly earned through development and investment as much as through security guarantees.

For Washington, the challenge lies in reconciling the desire to protect national interests with the realities of alliance management in a multipolar era. Tariffs, threats, and public confrontations may signal resolve domestically, but they can also push partners to hedge their bets internationally. The Arctic case illustrates how strategic pressure, when perceived as overreach, can produce the opposite of its intended effect—encouraging allies to seek balance rather than alignment.

None of this suggests that the United States is losing its capacity to shape global outcomes. Its economic scale, technological leadership, and network of alliances remain formidable. But the nature of influence is evolving. In regions like the Arctic, where long-term investment, scientific cooperation, and infrastructure development determine access and authority, power is exercised quietly and incrementally rather than through dramatic declarations.

The deeper lesson may lie in the unspoken reality of international politics: every nation, whether it proclaims it or not, puts its own interests first. What differentiates successful strategies is not the assertion of primacy, but the ability to align national goals with the aspirations of partners. When cooperation feels mutually beneficial, alliances endure; when it feels conditional or coercive, alternatives emerge.

As the ice recedes and shipping lanes open, the Arctic will continue to draw the attention of powers near and far. It will test whether established alliances can adapt to new economic and environmental realities, or whether emerging networks of partnership will redefine the region’s governance. In this unfolding story, China’s growing presence is not solely the result of its own ambition, but also of the spaces created by others’ missteps.

The coming years will reveal whether Washington chooses to recalibrate—investing in polar infrastructure, engaging allies in shared development plans, and framing Arctic security as a collective endeavor rather than a zero-sum contest. Such an approach could rebuild confidence and reassert leadership without forcing partners to choose sides.

If not, the Arctic may become a lasting symbol of a broader global shift: a world where influence flows toward those who build, connect, and invest, rather than those who command and confront. In that sense, the frozen north is no longer just a remote frontier—it is a mirror reflecting the changing dynamics of power in the twenty-first century.

-

Europe News12 months ago

Europe News12 months agoChaos and unproven theories surround Tates’ release from Romania

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoTrump Expels Zelensky from the White House

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoTrump expands exemptions from Canada and Mexico tariffs

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoZelensky bruised but upbeat after diplomatic whirlwind

-

Art & Culture12 months ago

Art & Culture12 months agoThe Indian film showing the bride’s ‘humiliation’ in arranged marriage

-

Pakistan News8 months ago

Pakistan News8 months agoComprehensive Analysis Report-The Faranian National Conference on Maritime Affairs-By Kashif Firaz Ahmed

-

Art & Culture12 months ago

Art & Culture12 months agoInternational Agriculture Exhibition held in Paris

-

Politics12 months ago

Politics12 months agoUS cuts send South Africa’s HIV treatment ‘off a cliff’