American News

U.S. Tariff Policies: A Historical Perspective

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY) :- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : Since its inception, the United States has oscillated between protectionist tariffs and free trade policies, shaping its economic and industrial landscape. Initially, tariffs were a primary revenue source for the federal government and a tool to protect fledgling industries from foreign competition. Over time, shifting economic priorities, political ideologies, and evolving global trade relations influenced U.S. tariff policies, each shift bringing both advantages and drawbacks. Protectionist tariffs have historically strengthened domestic industries but also led to trade disputes and higher consumer costs, while free trade policies have fostered global economic integration but often resulted in job losses in vulnerable sectors.

In the late 18th and 19th centuries, the U.S. relied on high tariffs to shield its developing industries from European competitors. The Tariff of 1816 and the Tariff of Abominations (1828) promoted Northern manufacturing by making foreign imports more expensive. However, these same policies harmed Southern agricultural exporters, who relied on overseas markets for cotton and tobacco sales. The Morrill Tariff (1861), introduced during the Civil War, reinforced protectionism, helping Northern industries but exacerbating regional tensions.

During this period, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany were America’s key trading partners. The UK, dependent on U.S. cotton for its textile industry, suffered the most from these tariffs. European manufacturers faced steep restrictions on their goods entering the U.S. market, leading to retaliatory tariffs that restricted American agricultural exports. This resulted in economic polarization, with industrialists in the North benefitting from tariff protections while Southern farmers and exporters suffered from declining international demand. Industries such as steel (Carnegie Steel), railroads (Union Pacific, Central Pacific), and manufacturing (Singer Sewing Machines, Colt Firearms, McCormick Harvesting Machines) thrived under these protectionist policies. However, Southern agriculture and the shipping industry struggled due to the loss of foreign markets. While tariffs fostered domestic industrial growth, they also deepened economic disparities and intensified sectional tensions that contributed to the Civil War.

The early 20th century saw fluctuations between free trade and protectionism, reflecting changing economic conditions. The Underwood Tariff (1913) under President Woodrow Wilson lowered tariffs significantly, improving trade relations with the UK, Germany, and France but reducing government revenue. However, the Fordney-McCumber Tariff (1922) reversed this trend, reinstating protectionist measures to support U.S. industries like steel, chemicals, and automobiles. While these tariffs strengthened domestic production, they provoked retaliatory tariffs from European nations, limiting U.S. exports and creating economic inefficiencies.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff (1930) under President Herbert Hoover significantly worsened the Great Depression by imposing some of the highest tariffs in U.S. history. This move triggered retaliatory measures from America’s key trading partners, collapsing global trade and accelerating the economic downturn. The U.S. economy shrank as agricultural and industrial exports plummeted, exacerbating the financial struggles of businesses and workers.

In response to the failures of extreme protectionism, the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (1934) under Franklin D. Roosevelt marked a decisive shift toward free trade. This act allowed the U.S. government to negotiate mutual tariff reductions with other countries, laying the groundwork for global economic cooperation. After World War II, this approach culminated in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT, 1947), promoting trade liberalization worldwide. Industries such as automobiles (Ford, General Motors), consumer goods (General Electric, RCA), and aircraft manufacturing (Boeing, Lockheed Martin) flourished due to expanding export markets and international cooperation. However, textiles and small-scale manufacturing struggled to compete with lower-cost imports, leading to job losses in some traditional American industries.

The impact on GDP was significant. While protectionist policies like Smoot-Hawley led to economic contraction, the shift toward free trade agreements fueled post-war prosperity, with U.S. GDP growing at an annual rate of 4%–5% in the 1950s and 1960s. However, as globalization accelerated, certain domestic industries faced intense foreign competition, leading to deindustrialization in some sectors.

The 21st century initially embraced globalization and free trade, with agreements like NAFTA (1994) and China’s WTO entry (2001) under Presidents Clinton and Bush expanding trade with Canada, Mexico, China, and the European Union. These agreements led to a surge in U.S. exports, particularly in technology (Apple, Intel, Microsoft), aerospace (Boeing), and agriculture (soybeans, corn, wheat). However, they also contributed to manufacturing job losses, as companies moved production to countries with lower labor costs. Domestic steel, textiles, and small manufacturing industries suffered as cheaper imports flooded the U.S. market, fueling political and economic discontent.

Under President Trump (2017–2021), the U.S. imposed tariffs on Chinese imports, steel, aluminum, and European goods, triggering a trade war aimed at protecting domestic industries. While these tariffs boosted U.S. steel and semiconductor production, they also raised costs for businesses dependent on foreign materials, such as automotive (General Motors, Ford), construction, and consumer electronics (Apple, Dell, HP). China retaliated with tariffs on American agricultural products, significantly impacting soybean and pork producers. The Biden administration (2021–2025) maintained most of these tariffs while focusing on domestic supply chains, semiconductor manufacturing (Intel, TSMC in Arizona), and renewable energy, benefiting defense and steel industries while hurting retail and agriculture due to higher import costs.

The impact on GDP was mixed. While globalization drove U.S. economic growth in the 1990s and early 2000s, with GDP expanding at 2%–3% annually, the U.S.-China trade war under Trump slowed investment and disrupted supply chains, causing GDP growth to drop to around 2% in 2019. Under Biden, continued tariffs contributed to inflation but also encouraged domestic industrial investment in semiconductors and clean energy.

In recent weeks, global stock markets have suffered sharp declines, largely due to escalating trade tensions and the impact of new tariffs. Major indices like the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 have experienced substantial losses, reflecting investor fears of an economic slowdown and the potential onset of a global recession. The energy sector has been particularly affected, with natural gas prices rising due to geopolitical instability and increased demand, leading to higher operational costs for industries reliant on energy.

However, there is potential for market recovery if specific conditions are met. A reduction in energy prices could lower production costs for businesses, improving corporate earnings and boosting investor confidence. Additionally, if protectionist trade policies successfully revitalize domestic manufacturing, the economy could see long-term benefits, reducing reliance on foreign imports and strengthening key industries. This could help stabilize financial markets and support economic growth.

While the short-term outlook remains uncertain, strategic policy adjustments—such as lowering energy prices, improving supply chain efficiency, and negotiating trade agreements that balance protectionism with economic openness—could pave the way for a more stable and prosperous market environment. If domestic industries adapt successfully, the U.S. economy may regain momentum, mitigating the negative effects of tariffs and restoring confidence in global markets.

American News

Armed man killed after entering secure perimeter of Trump’s residence, Secret Service says

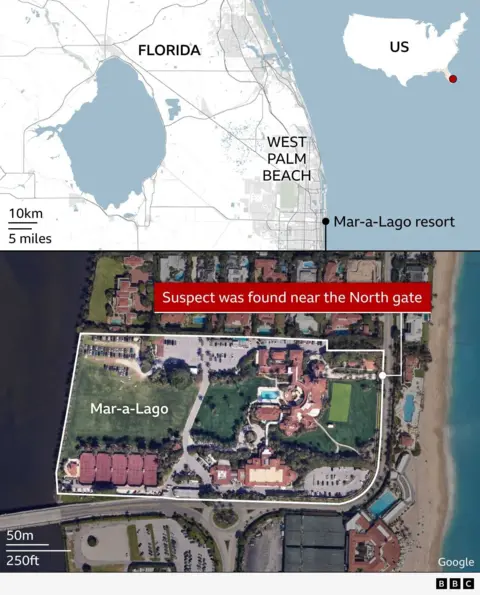

An armed man has been shot dead after entering the secure perimeter of US President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago residence in Florida, the Secret Service has said.

The man was carrying a shotgun and fuel can when he was stopped and shot by Secret Service agents and a Sheriff’s deputy, authorities said.

The incident happened around 01:30 ET (06:30 GMT) on Sunday morning, when the president was in Washington DC.

The suspect has been named as Austin T Martin of Cameron, North Carolina, according to the BBC’s US partner CBS.

His family in North Carolina had reported him missing in the early hours of Sunday morning, the Moore County Sheriff’s Office said in a statement to the BBC.

The missing persons information has since been turned over to federal authorities, the sheriff’s office said.

They added that the department had no prior history involving Martin and it was not involved in the Florida investigation.

Officials are looking into whether he bought the gun along the driving route he took from North Carolina to Florida, according to CBS.

Secret Service agents fired at him after they saw him “unlawfully entering the secure perimeter at Mar-a-Lago early this morning”, agency spokesman Anthony Guglielmi posted on X.

The suspect “was observed by the north gate of the Mar-a-Lago property carrying what appeared to be a shotgun and a fuel can”, the agency said in a statement.

The man was then shot after refusing orders, Palm Beach County sheriff Ric Bradshaw said.

“The only words that we said to him was ‘drop the items’ which means the gas can and the shotgun,” Bradshaw told a news conference.

“At which time he put down the gas can, raised the shotgun to a shooting position,” he said.

At that point, agents fired their weapons to “neutralise the threat”, he said.

The officers were wearing body cameras and no law enforcement officers were injured, he added.

Bradshaw said that he does not know if the suspect’s gun was loaded, and that will form part of an investigation, which the FBI will be assisting in.

US Secret Service Director Sean Curran travelled to Florida on Sunday for “after-actions” and has “reinvigorated operational communication and agency response to critical incidents”, the agency said in a post on X.

Security at Mar-a-Lago is extremely tight, with an outer cordon of local Palm Beach sheriffs and an inner one maintained by the Secret Service. Visitors are searched, and cars and bags are swept by dogs and metal detectors.

Trump has been the target of several assassination plots or attempts.

In July 2024, Trump was shot in the ear as he stood in front of crowds in Butler, Pennsylvania. One bystander was killed and two were injured in the shooting. The shooter, 20-year-old Matthew Crooks, was immediately shot and killed by security forces and his motive remains unknown.

Months later, a US Secret Service agent spotted a rifle sticking out of bushes at Trump International Golf Club in West Palm Beach. The man, later identified as Ryan Routh, fled but was caught. The 59-year-old was sentenced to life in prison earlier this month for attempting to assassinate the president.

During an appearance on Fox Business after the fatal incident, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent blamed the the political left for “normalising” political violence, citing the two attempts on Trump’s life in 2024,

“Two would-be assassins dead, one in jail for life, and this venom coming from the other side,” Bessent said, adding: “They are normalising this violence. It’s got to stop.”

Political violence has become a prominent issue in the US, sparking debate after a series of other high-profile incidents last year, including Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro’s mansion being set on fire, the fatal shootings of a Democratic lawmaker and her husband in Minnesota and the public shooting of right-wing activist Charlie Kirk.

American News

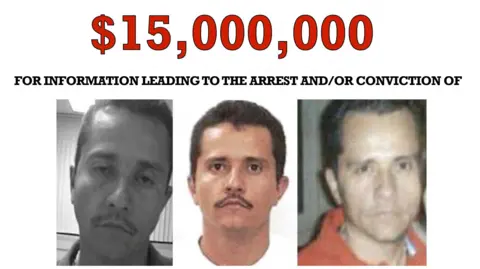

Violence erupts in Mexico after drug lord El Mencho killed

A wave of violence has broken out in Mexico after the country’s most wanted drug baron was killed in a security operation to arrest him involving US intelligence.

Nemesio Oseguera Cervantes, known as “El Mencho”, was the leader of the feared Jalisco New Generation (CJNG) drug cartel and died after being seriously injured in clashes between his supporters and the army on Sunday.

Four CJNG members were killed during the operation in the town of Tapalpa, in the central-western Jalisco state, and three army personnel were also injured, the Mexican defence ministry said.

Retaliation for the drug lord’s death has seen violence spread to at least a dozen states, with CJNG blocking roads with burning vehicles.

Throughout Sunday, there were reports of gunmen on the streets in Jalisco and elsewhere.

Eyewitnesses filmed plumes of smoke rising over several cities including Guadalajara – one of the host cities of the forthcoming Fifa World Cup.

Jalisco’s Governor Pablo Lemus Navarro declared a code red in the state, pausing all public transport and cancelling mass events and in-person classes.

Tourists who spoke to Reuters described the resort town of Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, as a “war zone”.

Some 250 roadblocks were in place across the country during the unrest, with 65 in Jalisco, the BBC’s US news partner CBS reported. In its latest update, the Mexican Security Cabinet said four blockades remained active in Jalisco.

The cabinet says 25 people have been arrested, 11 for their alleged participation in violent acts and 14 more for alleged looting and pillaging.

Shops were on fire and about 20 bank branches were attacked in the violence, it added.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum said there was “absolute coordination” between state and federal officials in response to the violence, urging people to stay “calm and informed”.

Sheinbaum added that “in most parts of the country, activities are proceeding normally”.

Several airlines have cancelled flights to Jalisco, including Air Canada, United Airlines and American Airlines.

The US has warned its citizens to shelter in place in five states: Jalisco, Tamaulipas, areas of Michoacán, Guerrero and Nuevo Leon.

The UK government said “serious security incidents” had been reported in Jalisco, adding “you should exercise extreme caution” and follow the advice of local authorities.

Late on Sunday night, US Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said El Mencho was a “top target for the Mexican and United States government as one of the top traffickers of fentanyl into our homeland.”

She said three cartel members had been killed, another three wounded and two arrested in the operation, for which the US had provided intelligence.

El Mencho, a 59-year-old former police officer, ran a vast criminal organisation responsible for trafficking huge quantities of cocaine, methamphetamine and fentanyl into the US.

The US State Department had offered a $15m (£11.1m) reward for information leading to El Mencho’s capture.

In a statement, the Mexican defence ministry said the operation was “planned and executed” by the country’s special forces.

Mike Vigil, former Chief of International Operations for the US Drug Enforcement Administration, described the operation as “one of the most significant actions undertaken in the history of drug trafficking”. He was speaking to CBS, the BBC’s US news partner.

American News

Trump Tariffs Ruled Unlawful

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY) :- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : On February 20, 2026, the United States Supreme Court delivered a historic rebuke to presidential power, striking down the sweeping tariffs imposed under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). By a 6–3 vote, the Court ruled that the 1977 law—designed to address extraordinary foreign threats during national emergencies—does not authorize a president to impose broad, open-ended tariffs. Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that while the president may “regulate” commerce under IEEPA, the statute contains no explicit reference to tariffs or duties. To read such vast taxing authority into two scattered words would, the Court concluded, represent a transformative expansion of executive power.

The decision did not touch tariffs imposed under other statutes, but it invalidated the most sweeping component of President Donald Trump’s tariff regime. Importantly, the Court declined to rule on whether or how the federal government must refund the enormous sums already collected. That question now looms as the most explosive consequence of the ruling.

For President Trump, tariffs were not merely policy—they were the centerpiece of his election campaign and a defining feature of his mandate. He framed them as a weapon to reclaim economic leverage from countries he argued had exploited American workers and industries. The message resonated with voters who felt the brunt of globalization. Tariffs were presented as a tool to rebuild manufacturing, force fair trade, and reassert American dominance.

Yet the mechanics of tariffs tell a different story. Tariffs are not paid by foreign governments; they are paid at U.S. ports by American importers. Over time, those costs either reduce corporate profit margins or are passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices. By late 2025 and early 2026, estimates suggested that more than $200 billion had been collected under the IEEPA-based tariffs alone. That staggering figure now hangs in legal limbo.

If the courts ultimately require refunds, the financial implications will be enormous. Even if a conservative estimate of $160–175 billion is used, the repayment obligation would constitute one of the largest refund processes in modern U.S. fiscal history. The U.S. Treasury would face a substantial budgetary shock. For small and medium-sized businesses, however, refunds could represent desperately needed relief.

Consider the arithmetic: if $160 billion were distributed across even 200,000 importing firms, the average recovery would approach $800,000 per business. For many small manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers operating on thin margins, such sums could mean rehiring workers, paying down debt, restoring inventory levels, or reinvesting in domestic operations.

Consumers, too, stand to benefit—though less directly. If even half of the tariff burden was passed on through price increases, households may have absorbed tens of billions of dollars in higher costs across groceries, appliances, auto parts, clothing, and everyday goods. The removal of unlawful tariffs could reduce price pressures and contribute to a modest easing of inflationary strain. While not a silver bullet, it would remove a structural cost layer embedded in supply chains.

Internationally, the ruling has complex implications. Countries such as Canada, Mexico, China, and members of the European Union were among the largest trading partners affected by the IEEPA tariffs. While they will not receive refund checks—because tariffs were paid by U.S. importers—the decision reduces friction in trade relationships. Canada, whose political relationship with Washington had grown tense over tariff disputes, may see this as an opportunity to recalibrate economic ties. European officials have already emphasized stability and predictability as priorities.

China, the largest source of targeted tariff revenue, will interpret the ruling as a constraint on unilateral American economic pressure. However, the decision does not eliminate other statutory tools such as Section 232 or Section 301, which remain available for targeted trade actions. Thus, the global message is not that America is retreating from trade leverage, but that its use must operate within clearer legal boundaries.

Domestically, the political impact is profound. Trump’s tariffs symbolized strength to his supporters and disruption to his critics. Now, the Supreme Court has reframed the issue from policy preference to constitutional authority. Democrats are likely to argue that the president imposed an unlawful tax on American businesses and consumers. Republicans may counter that the Court has weakened the executive’s ability to defend national economic interests.

Midterm elections will test which narrative prevails. If businesses begin receiving refunds and consumer prices ease, opponents of the tariff strategy may gain momentum. If, however, the administration pivots successfully to alternative statutory authorities and reestablishes elements of its trade framework, Trump may argue that the Court merely required procedural adjustments rather than policy abandonment.

Financial markets reacted swiftly and positively to the ruling, with equities rising on expectations of reduced trade uncertainty. Investors interpreted the decision as a move toward stability. Markets favor predictability, and the invalidation of sweeping emergency tariffs reduces the risk of abrupt cost shocks.

The ruling may also ripple through broader geopolitical calculations. In disputes involving Iran, Ukraine, NATO commitments, and trade alignments, allies and adversaries alike will note that American executive power is subject to judicial limits. The image of unrestrained economic unilateralism has been tempered. That could encourage diplomatic recalibration on multiple fronts.

Yet this is far from the end of tariff politics. Several federal statutes still grant the president authority to impose tariffs under defined conditions. Congress itself could legislate new trade measures. Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s dissent emphasized that the ruling might not significantly constrain future tariff actions if grounded in other statutory frameworks. In other words, the strategy may evolve rather than disappear.

The broader lesson extends beyond trade. The Court’s decision underscores a foundational principle of the American constitutional system: Congress holds the power to tax, and any delegation of that power must be explicit and limited. Emergency authority cannot become a blank check for transformative economic policy.

This moment may serve as a wake-up call. For the presidency, it is a reminder that campaign mandates must operate within constitutional boundaries. For Congress, it is a challenge to reclaim and exercise its Article I powers responsibly. For the United States globally, it signals that even in matters of economic warfare, the rule-based system still functions.

Trade disputes, geopolitical tensions, and domestic political battles will continue. But the Supreme Court’s ruling has drawn a bright line: power, however forcefully claimed, must rest on lawful authority. In doing so, the Court has not merely reshaped a tariff regime. It has reaffirmed the principle that in the United States, economic strategy—no matter how popular—cannot outrun the Constitution.

-

Europe News12 months ago

Europe News12 months agoChaos and unproven theories surround Tates’ release from Romania

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoTrump Expels Zelensky from the White House

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoTrump expands exemptions from Canada and Mexico tariffs

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoZelensky bruised but upbeat after diplomatic whirlwind

-

Art & Culture12 months ago

Art & Culture12 months agoThe Indian film showing the bride’s ‘humiliation’ in arranged marriage

-

Pakistan News8 months ago

Pakistan News8 months agoComprehensive Analysis Report-The Faranian National Conference on Maritime Affairs-By Kashif Firaz Ahmed

-

Art & Culture12 months ago

Art & Culture12 months agoInternational Agriculture Exhibition held in Paris

-

Politics12 months ago

Politics12 months agoUS cuts send South Africa’s HIV treatment ‘off a cliff’