World News

How Kentucky UPS plane crash unfolded and what could have caused it

At least nine people have died and 11 left injured after a UPS cargo plane crashed while taking off from an international airport in Louisville, Kentucky, on Tuesday evening.

Aviation experts who spoke to BBC Verify believe the plane crashed after one engine failed and another appeared to be damaged during take-off.

It is unclear what caused the plane to crash, prompting a massive fireball to erupt after it failed to take-off from the runway. Footage showed fire had already engulfed one wing of the aircraft while it was attempting to take off, which may have spread through the plane and caused the explosion, or the jet could have caught fire after colliding with an object on the ground.

What is apparent is that the 38,000 gallons (144,000 litres) of fuel on board the MD-11 jet needed for the flight likely escalated the blaze, which quickly spread to several buildings beyond the runway and burned for hours.

BBC Verify has been analysing footage that emerged overnight to piece together how the crash unfolded.

How did it start?

UPS uses Louisville Muhammad Ali International Airport as a distribution hub for its global operations and its Flight 2976 was at the start of a 4,300 mile journey to Honolulu in Hawaii when the cargo plane attempted to take off.

Data from tracking website FlightRadar24 shows the plane began to taxi along the 17R runway at around 17:15 local time (22:15 GMT) and managed to reach a top speed of 214mph (344km/h).

But verified footage shows that by the time the plane reached this speed a fire had completely engulfed its left wing and the aircraft struggled to climb away from the runway before the explosion.

Officials issued a shelter-in-place order to local residents and scrambled hundreds of firefighters to the scene.

Governor Andy Beshear confirmed details seen in CCTV footage that shows the aircraft flying just metres off the ground before a bright flash engulfed the plane. It is then seen slamming into the ground as a huge fireball erupts around it about a minute into its journey.

A verified clip taken by a motorists on a nearby highway showed the flames erupting into the skyline while later videos showed smoke billowing from the scene.

Aerial images broadcast by local media showed debris showering the runway and landing on the roofs of at least two local businesses.

What could have caused the crash?

Air traffic control communications reviewed by BBC Verify are largely garbled and full of interference so no meaningful conversation can be heard about the crash as it unfolded.

But analysts who spoke to BBC Verify suggested that a dramatic failure of two of the engines may have been responsible for the disaster.

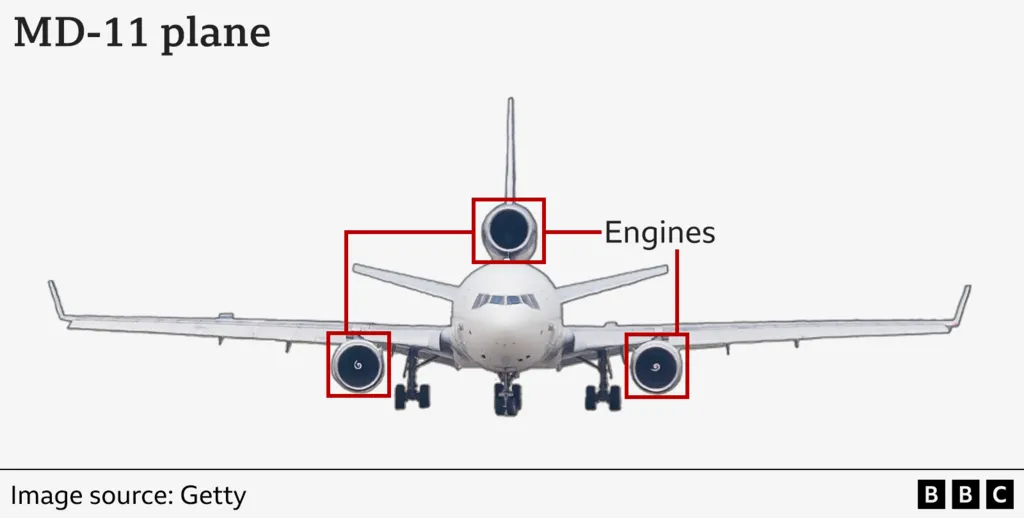

The MD-11 transport plane uses three engines. Two are mounted under the wings, and a third is built into the tail at the base of the vertical stabilizer.

Footage confirmed by BBC Verify showed a blaze engulfing the left wing of the plane, which then tilted to the left as it attempted to gain lift and take-off.

Two experts independently suggested the left engine may have detached from the plane after suffering from a mechanical or structural failure.

Separate images taken after the crash showed a charred engine sitting on the grass next to the runway at Louisville International Airport.

Terry Tozer, a retired airline pilot and aviation safety expert, told BBC Verify that it was “almost unheard of” for an engine to detach in flight.

He referenced the 1979 American Airlines Flight 191 disaster, in which 273 people were killed after the plane’s engine detached as it took off at O’Hare International Airport in Chicago. Parts of the engine had been damaged when it was replaced on the plane, but Mr Tozer said it was too early to say whether a similar fault caused the engine to detach on the MD-11.

Mr Tozer said the cargo plane would have been able to fly with just two engines but the damage caused by the fire on the left wing was likely so great it caused the plane’s engine built into the tail to lose thrust.

“With such a catastrophic event we cannot know what other damage was done when the engine came adrift,” he said.

Marco Chan, a senior lecturer in aviation operations at Buckinghamshire New University, said the footage appeared to show the third engine had been damaged because it expelled a burst of smoke. The damage could have happened while it was pelted with debris from the fire and the engine detaching.

“The upper engine that expelled a puff of smoke appears to wind down almost immediately afterwards,” Mr Chan said. “That left only the right engine producing thrust, creating a severe power imbalance and leaving the aircraft unable to gain height.

“Losing two engines during take-off leaves the aircraft with only a third of its power and little chance of maintaining flight, especially at maximum take-off weight,” Mr Chan added.

Why did the crash cause such damage?

Footage from the aftermath of the crash showed a scene of complete chaos with multiple fires blazing across a large swathe of the site and smoke billowing into the sky.

The plane, which was 34 years old and had been used as a passenger plane until 2006, had already completed one return journey from Louisville on Tuesday to Baltimore in Maryland.

It has not been confirmed what cargo was on board the flight bound for Hawaii, though officials said the plane was not carrying anything that would create a heightened risk of contamination.

“This was a long-haul cargo flight from Louisville to Honolulu, so the MD-11 was carrying a lot of jet fuel,” Mr Chan said. “That heavy fuel load not only reduced performance but also explains the large fireball seen after the crash.”

Officials told reporters that the aircraft was carrying 38,000 gallons (144,000 litres) of fuel for the long journey when it crashed. The blaze was likely amplified on the ground because the aircraft slammed into a fuel recycling business next to the airport.

Mr Chan said investigators will now focus on how the initial fire began, and “whether debris struck the centre engine, and whether earlier maintenance on the left engine played a role”. He added: “Weather conditions were calm and clear, so environmental factors are unlikely.”

The National Transportation Safety Board (NSTB) has sent a team to the site and will now lead the investigation into the causes of the crash, though this can take up to two years to complete.

Additional reporting by Emma Pengelly, Kayleen Devlin and Paul Brown.

World News

‘National security is non-negotiable’: Parliamentary secretary on Afghanistan strikes

ISLAMABAD: Parliamentary Secretary for Information and Broadcasting Barrister Danyal Chaudhry on Monday stressed that national security was “non-negotiable” after Pakistan carried out strikes on terrorist targets in Afghanistan, killing over 80 terrorists.

“Pakistan has always chosen the path of dialogue and peaceful coexistence. But when Afghan soil continues to be used for proxy attacks, we have no choice but to defend our homeland. National security is non-negotiable,” Chaudhry said in a statement.

The PML-N MNA affirmed that the people of Pakistan “stand firmly” with their armed forces in the fight against terrorism.

He urged the Afghan government to take “decisive action to prevent its land from being used for cross-border militancy”, warning that lasting peace in the region depended on the “complete dismantling of terrorist sanctuaries”.

Noting that the recent operation “successfully neutralised militants involved in attacks on Pakistani soil”, Chaudhry stressed: “This action was aimed solely at those responsible for violent attacks inside Pakistan. Every precaution was taken to protect innocent lives.”

He also pointed to Afghanistan’s emergence as a “sanctuary for multiple terrorist groups”. Referring to a United Nations report, he noted that militants from 21 terror outfits were operating from Afghan territory, posing a serious threat to regional stability.

He specifically called out India’s “continued support for terrorist networks”.

“India is actively funding and training these groups, equipping them to carry out cross-border attacks against Pakistan. Such elements deserve no concessions,” the parliamentary secretary asserted.

His remarks came after Pakistan carried out airstrikes on Afghanistan in a retaliatory operation targeting groups responsible for recent suicide bombings in Pakistan.

The strikes killed “more than 80 terrorists”, according to security sources.

The strikes were conducted in retaliation for a series of suicide attacks in Islamabad, Bajaur, and Bannu that had claimed the lives of Pakistani security personnel and civilians. Authorities described the operation as intelligence-based and proportionate, aimed solely at those responsible for the attacks.

‘Decisive struggle against terrorism’

Separately, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Governor Faisal Karim Kundi asserted that the country will “not allow our soil to be destabilised by forces operating from across the border in Afghanistan”.

In a post on X, he said: “The citizens of Pakistan, especially the resilient people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, stand firmly with our armed forces and security institutions in the defense of our homeland.”

He further said: “The sacrifices of our martyrs bind us together as one nation. In this decisive struggle against terrorism, Pakistan stands united, resolute, and unwavering.

“Our sovereignty is non-negotiable, and the people of this country stand shoulder to shoulder with the state to protect it at all costs.”

World News

More than 1,500 Venezuelan political prisoners apply for amnesty

A total of 1,557 Venezuelan political prisoners have applied for amnesty under a new law introduced on Thursday, the country’s National Assembly President has said.

Jorge Rodríguez, brother of Venezuelan interim President Delcy Rodríguez and an ally of former President Nicolás Maduro, also said “hundreds” of prisoners had already been released.

Among them is politician Juan Pablo Guanipa, one of several opposition voices to have criticised the law for excluding certain prisoners.

The US has urged Venezuela to speed up its release of political prisoners since US forces seized Maduro in a raid on 3 January. Venezuela’s socialist government has always denied holding political prisoners.

At a news conference on Saturday Jorge Rodríguez said 1,557 release requests were being addressed “immediately” and ultimately the legislation would extend to 11,000 prisoners.

The government first announced days after Maduro’s capture, on 8 January, that “a significant number” of prisoners would be freed as a goodwill gesture.

Opposition and human rights groups have said the government under Maduro used detentions of political prisoners to stamp out dissent and silence critics for years.

These groups have also criticised the new law. One frequently cited criticism is that it would not extend amnesty to those who called for foreign armed intervention in Venezuela, BBC Latin America specialist Luis Fajardo says.

He noted that law professor Juan Carlos Apitz, of the Central University of Venezuela, told CNN Español that that part of the amnesty law “has a name and surname”. “That paragraph is the Maria Corina Machado paragraph.”

It is not clear if the amnesty would actually cover Machado, who won last year’s Nobel Peace Prize, Fajardo said.

He added that other controversial aspects of the law include the apparent exclusion from amnesty benefits of dozens of military officers involved in rebellions against the Maduro administration over the years.

On Saturday, Rodríguez said it is “releases from Zona Seven of El Helicoide that they’re handling first”.

Those jailed at the infamous prison in Caracas would be released “over the next few hours”, he added.

Activists say some family members of those imprisoned in the facility have gone on hunger strike to demand the release of their relatives.

US President Donald Trump said that El Helicoide would be closed after Maduro’s capture.

Maduro is awaiting trial in custody in the US alongside his wife Cilia Flores and has pleaded not guilty to drugs and weapons charges, saying that he is a “prisoner of war”.

World News

Iran students stage first large anti-government protests since deadly crackdown

Students at several universities in Iran have staged anti-government protests – the first such rallies on this scale since last month’s deadly crackdown by the authorities.

The BBC has verified footage of demonstrators marching on the campus of the Sharif University of Technology in the capital Tehran on Saturday. Scuffles were later seen breaking out between them and government supporters.

A sit-in was held at another Tehran university, and a rally reported in the north-east. Students were honouring thousands of those killed in mass protests in January.

The US has been building up its military presence near Iran, and President Donald Trump has said he is considering a limited military strike.

The US and its European allies suspect that Iran is moving towards the development of a nuclear weapon, something Iran has always denied.

US and Iranian officials met in Switzerland on Tuesday and said progress had been made in talks aimed at curbing Iran’s nuclear programme.

But despite the reported progress, Trump said afterwards that the world would find out “over the next, probably, 10 days” whether a deal would be reached with Iran or the US would take military action.

The US leader has supported protesters in the past – at one stage appearing to encourage them with a promise that “help is on its way”.

Footage verified by the BBC shows hundreds of protesters – many with national Iranian flags – peacefully marching on the campus of the Sharif University of Technology at the start of a new semester on Saturday.

The crowds chanted “death to the dictator” – a reference to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei – and other anti-government slogans.

Supporters of a rival pro-government rally are seen nearby in the video. Scuffles are later seen breaking out between the two camps.

Verified photos have also emerged showing a peaceful sit-in protest at the capital’s Shahid Beheshti University.

The BBC have also verified footage from another Tehran university, Amir Kabir University of Technology, showing chanting against the government.

In Mashhad, Iran’s second-largest city in the north-east, local students reportedly chanted: “Freedom, freedom” and “Students, shout, shout for your rights”.

Sizeable demonstrations in other locations were also reported later in the day, with calls for further rallies on Sunday.

It is not immediately clear whether any demonstrators have been arrested.

Last month’s protests began over economic grievances and soon spread to become the largest since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

The US-based Human Rights Activists News Agency (Hrana) said it had confirmed the killing of at least 6,159 people during that wave, including 5,804 protesters, 92 children and 214 people affiliated with the government.

Hrana also said it was investigating 17,000 more reported deaths.

Iranian authorities said late last month that more than 3,100 people had been killed – but that the majority were security personnel or bystanders attacked by “rioters”.

Saturday’s protests come as the Iranian authorities are preparing for a possible war with the US.

The exiled opposition is adamantly calling on President Trump to make good on his threats and strike, hoping for a quick downfall of the current hardline government.

But other opposition groups are opposed to outside intervention.

The opposing sides have been involved in disinformation campaigns of social media, trying to maximise their conflicting narratives of what Iranian people want.

Additional reporting by BBC Persian’s Ghoncheh Habibiazad, and BBC Verify’s Richard Irvine-Brown and Shayan Sardarizadeh.

-

Europe News12 months ago

Europe News12 months agoChaos and unproven theories surround Tates’ release from Romania

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoTrump Expels Zelensky from the White House

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoTrump expands exemptions from Canada and Mexico tariffs

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoZelensky bruised but upbeat after diplomatic whirlwind

-

Art & Culture12 months ago

Art & Culture12 months agoThe Indian film showing the bride’s ‘humiliation’ in arranged marriage

-

Pakistan News8 months ago

Pakistan News8 months agoComprehensive Analysis Report-The Faranian National Conference on Maritime Affairs-By Kashif Firaz Ahmed

-

Art & Culture12 months ago

Art & Culture12 months agoInternational Agriculture Exhibition held in Paris

-

Politics12 months ago

Politics12 months agoUS cuts send South Africa’s HIV treatment ‘off a cliff’