Pakistan News

How India and Pakistan share one of the world’s most dangerous borders

To live along the Line of Control (LoC) – the volatile de facto border that separates India and Pakistan – is to exist perpetually on the razor’s edge between fragile peace and open conflict.

The recent escalation after the Pahalgam attack brought India and Pakistan to the brink once again. Shells rained down on both sides of the LoC, turning homes to rubble and lives into statistics. At least 16 people were reportedly killed on the Indian side, while Pakistan claims 40 civilian deaths, though it remains unclear how many were directly caused by the shelling.

“Families on the LoC are subjected to Indian and Pakistani whims and face the brunt of heated tensions,” Anam Zakaria, a Pakistani writer based in Canada, told the BBC.

“Each time firing resumes many are thrust into bunkers, livestock and livelihood is lost, infrastructure – homes, hospitals, schools – is damaged. The vulnerability and volatility experienced has grave repercussions for their everyday lived reality,” Ms Zakaria, author of a book on Pakistan-administered Kashmir, said.

India and Pakistan share a 3,323km (2,064-mile) border, including the 740km-long LoC; and the International Border (IB), spanning roughly 2,400km. The LoC began as the Ceasefire Line in 1949 after the first India-Pakistan war, and was renamed under the 1972 Simla Agreement.

The LoC cutting through Kashmir – claimed in full and administered in parts by both India and Pakistan – remains one of the most militarised borders in the world. Conflict is never far behind and ceasefires are only as durable as the next provocation.

Ceasefire violations here can range from “low-level firing to major land grabbing to surgical strikes“, says Happymon Jacob, a foreign policy expert at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). (A land grab could involve seizing key positions such as hilltops, outposts, or buffer zones by force.)

The LoC, many experts say, is a classic example of a “border drawn in blood, forged through conflict”. It is also a line, as Ms Zakaria says, “carved by India and Pakistan, and militarised and weaponised, without taking Kashmiris into account”.

Such wartime borders aren’t unique to South Asia. Sumantra Bose, professor of international and comparative politics at Krea University in India and author of Kashmir at the Crossroads: Inside a 21st-Century Conflict, says the most well-known is the ‘Green Line’ – the ceasefire line of 1949 – which is the generally recognised boundary between Israel and the West Bank.

Not surprisingly, the tentative calm along the LoC that had endured since the 2021 ceasefire agreement between the two nuclear-armed neighbours crumbled easily after the latest hostilities.

“The current escalation on the LoC and International Border (IB) is significant as it follows a four-year period of relative peace on the border,” Surya Valliappan Krishna of Carnegie India told the BBC.

Violence along the India-Pakistan border is not new – prior to the 2003 ceasefire, India reported 4,134 violations in 2001 and 5,767 in 2002.

The 2003 ceasefire initially held, with negligible violations from 2004 to 2007, but tensions resurfaced in 2008 and escalated sharply by 2013.

Between 2013 and early 2021, the LoC and the IB witnessed sustained high levels of conflict. A renewed ceasefire in February 2021 led to an immediate and sustained drop in violations through to March 2025.

“During periods of intense cross-border firing we’ve seen border populations in the many thousands be displaced for months on end,” says Mr Krishna. Between late September and early December 2016, more than 27,000 people were displaced from border areas due to ceasefire violations and cross-border firing.

It’s looking increasingly hairy and uncertain now.

Tensions flared after the Pahalgam attack, with India suspending the key water-sharing treaty between India and Pakistan, known as the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT). Pakistan responded by threatening to exit the 1972 Simla Agreement, which formalised the LoC – though it hasn’t followed through yet.

“This is significant because the Simla Agreement is the basis of the current LoC, which both sides agreed to not alter unilaterally in spite of their political differences,” says Mr Krishna.

Mr Jacob says for some “curious reason”, ceasefire violations along the LoC have been absent from discussions and debates about escalation of conflict between the two countries.

“It is itself puzzling how the regular use of high-calibre weapons such as 105mm mortars, 130 and 155mm artillery guns and anti-tank guided missiles by two nuclear-capable countries, which has led to civilian and military casualties, has escaped scholarly scrutiny and policy attention,” Mr Jacob writes in his book, Line On Fire: Ceasefire Violations and India-Pakistan Escalation Dynamics.

Mr Jacob identifies two main triggers for the violations: Pakistan often uses cover fire to facilitate militant infiltration into Indian-administered Kashmir, which has witnessed an armed insurgency against Indian rule for over three decades. Pakistan, in turn, accuses India of unprovoked firing on civilian areas.

He argues that ceasefire violations along the India-Pakistan border are less the product of high-level political strategy and more the result of local military dynamics.

The hostilities are often initiated by field commanders – sometimes with, but often without, central approval. He also challenges the notion that the Pakistan Army alone drives the violations, pointing instead to a complex mix of local military imperatives and autonomy granted to border forces on both sides.

Some experts believe It’s time to revisit an idea shelved nearly two decades ago: turning the LoC into a formal, internationally recognised border. Others insist that possibility was never realistic – and still isn’t.

“The idea is completely infeasible, a dead end. For decades, Indian maps have shown the entire territory of the erstwhile princely state of Jammu and Kashmir as part of India,” Sumantra Bose told the BBC.

“For Pakistan, making the LoC part of the International Border would mean settling the Kashmir dispute – which is Pakistan’s equivalent of the Holy Grail – on India’s preferred terms. Every Pakistani government and leader, civilian or military, over the past seven decades has rejected this.”

In his 2003 book, Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace, Prof Bose writes: “A Kashmir settlement necessitates that the LoC be transformed – from an iron curtain of barbed wire, bunkers, trenches and hostile militaries to a linen curtain. Realpolitik dictates that the border will be permanent (albeit probably under a different name), but it must be transcended without being abolished.”

“I stressed, though, that such a transformation of the LoC must be embedded in a broader Kashmir settlement, as one pillar of a multi-pillared settlement,” he told the BBC.

Between 2004 and 2007, turning the LoC into a soft border was central to a fledgling India-Pakistan peace process on Kashmir – a process that ultimately fell apart.

Today, the border has reignited, bringing back the cycle of violence and uncertainty for those who live in its shadow.

“You never know what will happen next. No one wants to sleep facing the Line of Control tonight,” an employee of a hotel in Pakistan-administered Kashmir told BBC Urdu during the recent hostilities.

It was a quiet reminder of how fragile peace is when your window opens to a battlefield.

Pakistan News

Pakistan launches strikes on Afghanistan, with Taliban saying dozens killed

Pakistan has carried out multiple overnight air strikes on Afghanistan, which the Taliban has said killed and wounded dozens of people, including women and children.

Islamabad said the attacks targeted seven alleged militant camps and hideouts near the Pakistan-Afghanistan border and that they had been launched after recent suicide bombings in Pakistan.

Afghanistan condemned the attacks, saying they targeted multiple civilian homes and a religious school.

The fresh strikes come after the two countries agreed to a fragile ceasefire in October following deadly cross-border clashes, though subsequent fighting has taken place.

The Taliban’s defence ministry said the strikes targeted civilian areas of Nangarhar and Paktika provinces.

Officials in Nangarhar told the BBC that the home of a man called Shahabuddin had been hit by one of the strikes, killing about 20 family members, including women and children.

Pakistan’s Ministry of Information and Broadcasting said it had carried out “intelligence based selective targeting of seven terrorist camps and hideouts”.

In a statement on X, it said the targets included members of the banned Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan, which the government refers to as “Fitna al Khawarij,” along with their affiliates and the Islamic State-Khorasan Province.

The ministry described the strikes as “a retributive response” to recent suicide bombings in Pakistan by terror groups it said were sheltered by Kabul.

The recent attacks in Pakistan included one on a Shia mosque in the capital Islamabad earlier this month, as well as others that took place since the holy month of Ramadan began this week in the north-western Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

Pakistan accused the Afghan Taliban of failing to take action against the militants, adding that it had “conclusive evidence” that the attacks were carried out by militants on the instructions of their leadership in Afghanistan.

The Taliban’s defence ministry later posted on X condemning the attacks as a “blatant violation of Afghanistan’s territorial integrity”, adding that they were a “clear breach of international law”.

It warned that “an appropriate and measured response will be taken at a suitable time”, adding that “attacks on civilian targets and religious institutions indicate the failure of Pakistan’s army in intelligence and security.”

The strikes come days after Saudi Arabia mediated the release of three Pakistani soldiers earlier this week, who were captured in Kabul during border clashes last October.

Those clashes ended with a tentative ceasefire that same month after the worst fighting since the Taliban returned to power in 2021.

Pakistan and Afghanistan share a 1,600-mile (2,574 km) mountainous border.

Pakistan News

KASHMIR SOLIDARITY DAY AND HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION IN INDIAN-OCUPIED JAMMU AND KASHMIR

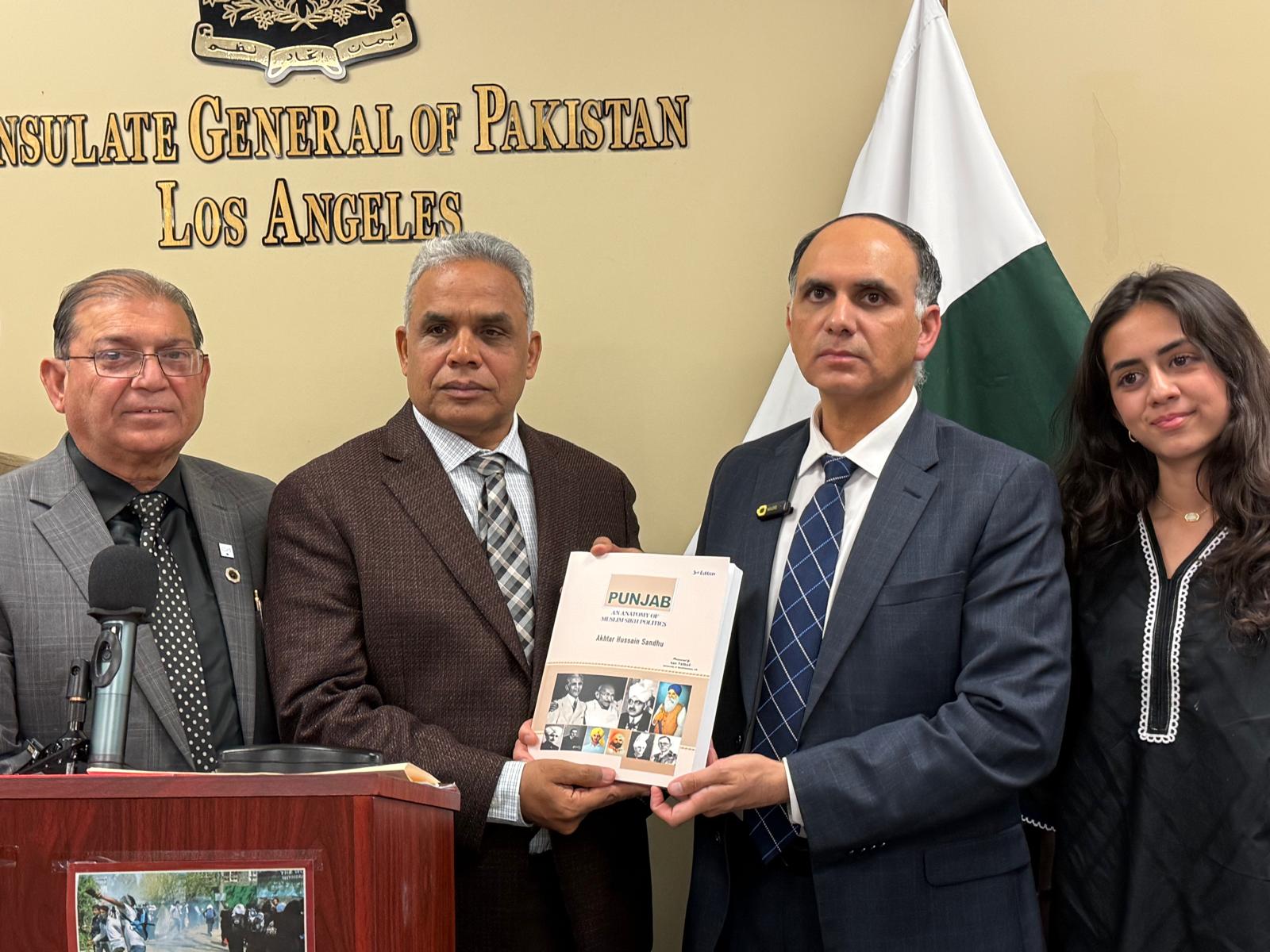

Consulate General of Pakistan, Los Angeles (USA)

Akhtar Hussain Sandhu

California (USA)

Every year, 5th February is observed as Kashmir Solidarity Day in Pakistan, Kashmir, and in different parts of the world where Pakistanis are residing. The main purpose of observing the day is to honor the freedom struggle of the Kashmiri people against the human rights violations in the Indian-occupied Jammu & Kashmir. It also aims at highlighting the human rights violations by the Indian government and the forces to attract the world community’s attention to the plight of the Muslims. Pakistan supports this struggle for its right to self-determination as enunciated in the United Nations’ charter (Articles 1(2) and 55) and the pledge of a plebiscite in Kashmir made by the Indian government. The Consulate General of Pakistan, Los Angeles (USA), arranged a meeting on 4 February 2026 in which the Muslims and Sikhs participated to express their solidarity with the people of Jammu & Kashmir. Consul General Asim Ai Khan inaugurated the session with the messages of the President, Prime Minister, and Foreign Minister of Pakistan.

Asim Ali Khan introduced the audience to the background and importance of 5th February. He reiterated the national stance of the Pakistani government that they would always support the Kashmiri freedom struggle and would condemn the brutality of the Indian armed forces in the Indian-occupied Jammu and Kashmir. This was my first appearance as a speaker at an official event, and the arrangements and the audience’s deep interest in Pakistan’s state narrative encouraged me to believe that one day the struggle of the Kashmiri people will bring a shining dawn for posterity. Besides Asim Ali Khan, the host, eminent journalist Arif Zaffar Mansuri, Dr. Akhtar Hussain Sandhu, Sultan Ahmed, and Ismail Keekibhai expressed their concern about the ongoing suffering of the Kashmiri people and pledged full support from the Pakistani government and people. Arif Mansuri said that the international community ought to come forward to rescue the oppressed from the Indian forces and their inhuman treatment of the innocent Muslims of the Indian-occupied J&K.

The program was conducted by a talented young girl, Asma Khan, who beautifully started and ended the seminar. she played a documentary which highlighted beauty of the valley, facts and figures of the martyrs and brutality of the BJP government. Sultan Ahmad, with an impressive administrative and political portfolio in the US, reminded the audience to spread this message at a higher level and that he would be a helping hand in exposing India’s nefarious intentions and human rights violations. I had been invited by Mubashir Khan (Deputy Consul General), but he was in Pakistan, so we could not meet on the occasion. I shared my view that this is a dilemma of human history: humans inflict barbarity upon humans. But the redeeming aspect is that humans endeavor to support the oppressed and condemn the aggressor. Humans ensure and restore peace. It is often perceived that philosophical and technological advanceshaveopened new avenues for conflict resolution and appeasement. Fatality of the wars experienced especially during the 20th century made the world realize to establish a forum of reconciliation, the League of Nations and United Nations, to block the way to future wars and violence settling the dispute through dialogue and negotiations. Civil society organizations, universities, peace-loving projects, published material, and media keep on highlighting the importance of peace, coexistence, interfaith harmony, minority rights, protection of vulnerable social groups, including minority, women, children and the aged, but despite all this exhortation, we see inhuman treatment and brutality in many parts of the world. Look at Jammu & Kashmir administered by India, wherein the innocent Muslims are going through ordeals such as torture, sexual violence, extrajudicial killing, ban of expression, detention, unjustifiable deployment of Indian forces, and psychological hammering. No human ethics and international humanitarian laws allow this maltreatment and repressive measures that the people of Jammu & Kashmir have been experiencing for many decades. The BJP government changed the political and geographical status of Jammu & Kashmir after the revocation of Articles 370 and 35A on 5 August 2019, depriving J&K of its Special Sovereign Status. Although it is never welcomed by the majority of the Kashmiri people but the Indian government did not listen to the people of J&K. Even the Indian Supreme Court on 11 December 2023 upheld the government’s revocation of 370 and 35A and gave observation, JK had no internal sovereignty after its ‘accession’ to India although‘accession’ is a disputed issue and the matter is still pending in the UN. Many dissidents were imprisoned and many have been facing police and court cases. The Indian governments concluded laws, acts such as Public Safety Act and even amendments to justify their repressive and oppressive attitude. Amnesty International expressed concern over the arrests of Muslim and Hindu leaders.

Pakistan is usually blamed by the Indian government for supporting the Kashmiri Muslims, but why were the Hindu leaders arrested by the Indian government? This is to prove that even the Hindus support the Pakistan’s stance on the issue of human rights. The Americans have just celebrated Martin Luther King, Jr.’s day with the message that ‘violence breeds more violence’ and ‘unjust laws are laws at all… and it is a moral duty to defy the unjust laws,’ therefore, the Americans ought to defy unjust laws which are contradictory to human or natural rights.’ Right now, the people of Indian-Occupied Jammu & Kashmir are victims of unjust laws and inhuman treatment by the BJP government. Not only Muslims of the Indian-Occupied J&K, but also the Christians, Achhoot, and Sikhs are also undergoing cruel and ill-treatment. Investigation concludes that the Indian-sponsored killing squad assassinated and targeted the Sikh leaders in England, Canada, Pakistan and the US. It is a moral obligation of the international community to redeem the oppressed people from the tyrannical and dictatorial rule of the Indian government under the Bhartiya Janata Party. Moreover, I do appreciate the international organizations and countries which raise their voice against the violation of human rights in Indian-Occupied J&K as yes, the oppressed Kashmiri people do need the international support in the name of humanity so that the coming generations of the valley can be saved from such a physical torture and mental agony. The world community should become the voice of the voiceless people and ensure the following:

- Withdrawal of the Indian armed forces from the Indian-occupied J&K must be ensured immediately so that the people can live a normal and peaceful life.

- The autonomous status of the Indian-Occupied J&K should be restored to what it was in 2019. Intention to change the demography of the valley must be blocked, and property once owned by the local Kashmiris must be returned to the previous Kashmiri owners.

- A UN resolution to hold a plebiscite in Kashmir is the best way to determine the will of the people.

- An inquiry under the UN umbrella should be conducted to investigate police and court cases against locals in the valley. The findings should be made public so that the world can come to know what brutality has been inflicted upon the innocent people of Indian-occupied J&K.

- The civil society organizations, media people, and UN delegations should be facilitated to visit the region to collect the facts relating to abuse of authority, violence, torture, ban on expression and religious rituals, presence of the Indian army, and police cases against the youth. Fake encounters should also be stopped, and the judicial proceedings should be monitored by the UN emissary.

Consul General Asim Ai Khan thanked the scholars and audience. At the end of the program, Navdeep Singh and I presented the 3rd edition of my book, Punjab: An Anatomy of Muslim-Sikh Politics, to Consul General Asim Ai Khan. All the participants gathered in the hall and shared their thought on the subject with each other. This was a great day that sensitized many Muslim and Sikh people about international politics and the violation of human rights in different regions of the world. If this generation plans to convert the world into a peaceful place for posterity, they will have to condemn state violence and extremism existing anywhere in the world.

Pakistan News

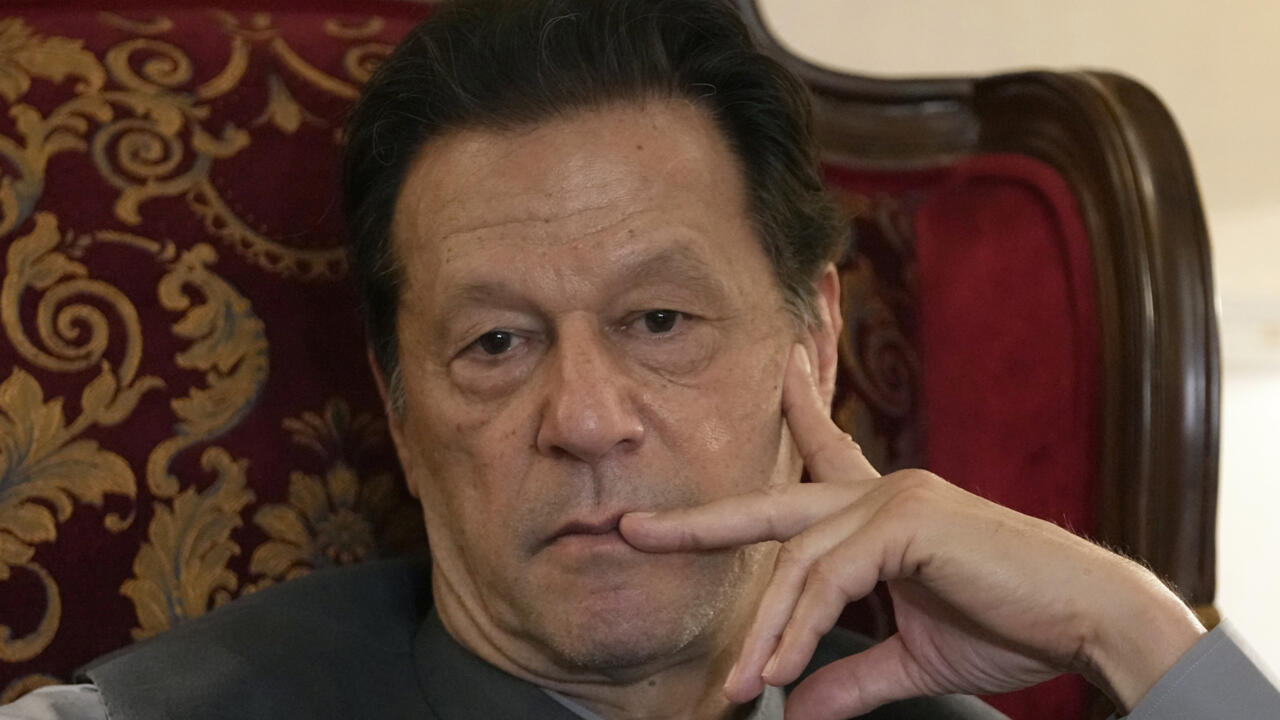

The Epstein Files Set Imran Khan Apart

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY) :- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : When the latest waves of documents connected to the Jeffrey Epstein investigation began surfacing, most of the names that appeared followed a familiar and uncomfortable pattern. The references revolved around social proximity, elite networks, reputational damage, and questions of judgment. Against that backdrop, one name stood apart — not because of scandal, but because of how it was framed.

Imran Khan’s reported mention was different. According to summaries that emerged from the broader document releases, he was not linked to misconduct or impropriety. Instead, he was described in private correspondence as “really bad news” and a “greater threat.” The tone was political rather than personal, strategic rather than social. In a collection of files that cast shadows over many reputations, his distinction appeared to lie in geopolitical discomfort rather than scandal.

That difference matters because it shifts the conversation from morality to strategy. A leader described as a threat is not being accused of vice but of independence. The question then becomes: dangerous to whom, and for what reason? To understand why that framing resonates so strongly in Pakistan, one must revisit a moment that altered the country’s political trajectory. That moment arrived in early March 2022.

On August 9, 2023, The Intercept published a classified Pakistani diplomatic cable documenting a March 7, 2022 meeting between Pakistan’s ambassador to Washington and U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Donald Lu. The document, labeled “Secret,” recorded Washington’s displeasure with Khan’s visit to Moscow on February 24, 2022 — the very day Russia invaded Ukraine. According to the cable, Lu stated that if a no-confidence vote against Prime Minister Khan succeeded, “all will be forgiven in Washington.” Otherwise, he warned, it would be “tough going ahead,” and the prime minister could face “isolation” from Europe and the United States.

The language recorded in the cable is unmistakably conditional, tying bilateral warmth to a specific political outcome. Forgiveness if he is removed; difficulty if he remains.

The sequence that followed intensified scrutiny. The meeting took place on March 7, procedural steps toward a no-confidence vote began on March 8, and by April 10, Khan had been removed from office. Correlation does not prove orchestration, and political transitions are rarely explained by a single document. Nevertheless, the cable demonstrates that diplomatic pressure was applied at a sensitive moment. It also reveals that Washington viewed Khan’s neutrality on Ukraine as a personal policy choice rather than institutional consensus.

Khan’s foreign policy posture had consistently emphasized strategic independence. He refused to grant U.S. military basing rights after America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, publicly declaring “Absolutely not” when asked about hosting foreign forces. He defended Pakistan’s abstention at the United Nations on Ukraine and rejected public pressure from European diplomats, asking pointedly at a rally whether Pakistan was expected to behave as a subordinate state. He argued that engagement with Russia was necessary to secure affordable energy and food for Pakistan’s struggling population.

Beyond Ukraine, Khan elevated the issue of Islamophobia on the global stage, pressing the United Nations to recognize anti-Muslim discrimination and urging respect for religious dignity. He framed Pakistan as a country that would engage with all powers without entering rigid alliances. Supporters viewed this as sovereignty in action, while critics considered it diplomatic miscalculation. What cannot be denied is that his posture disrupted established expectations about alignment in a polarized global environment.

Following his removal, Pakistan’s external positioning shifted noticeably. Military-to-military engagement with the United States regained momentum, and reports surfaced of Pakistani-manufactured ammunition appearing in Ukraine. Diplomatic warmth between Islamabad and Western capitals returned, and new defense cooperation frameworks were discussed. These developments do not conclusively prove that pressure determined political outcomes, but they align with the cable’s suggestion that a change in leadership would ease tensions and remove the “dent” in relations.

It is within this broader context that the contrast with the Epstein-related references acquires symbolic weight. Many powerful men whose names appeared in those documents faced reputational questions because of association with a disgraced financier. Imran Khan’s distinction, by contrast, was reportedly rooted in strategic apprehension rather than personal scandal. He was not depicted as compromised; he was characterized as disruptive.

The cable published by The Intercept reinforces that interpretation. Its “assessment” section records the Pakistani ambassador’s view that Lu could not have delivered such a strong message without approval from higher authorities. Whether or not that assessment was accurate, it underscores how the exchange was perceived inside Pakistan’s diplomatic apparatus. The document captures a moment when international expectations and domestic politics collided.

Since Khan’s removal, Pakistan has experienced deep polarization, economic strain, and intensified debate over the balance of civilian and military authority. His critics argue that his governance record warranted parliamentary removal and that institutional checks functioned as designed. His supporters argue that his defiance of geopolitical alignment invited external pressure that altered the course of domestic politics. The truth may reside in the interplay of both internal and external forces.

What the documentary record shows is not a signed directive of regime change, but evidence of diplomatic leverage. In international politics, leverage often operates through incentives and signals rather than commands. The phrase “all will be forgiven” is not an order; it is a conditional promise. Such language does not prove conspiracy, but it does demonstrate expectation.

That is why the distinction matters. The Epstein files, as publicly discussed, did not place Imran Khan among scandal-tainted elites. Instead, they appear to reflect concern about his independent trajectory. The March 7 cable then provides context for why that concern may have existed, showing that his policies generated friction at the highest levels of diplomacy. In a world structured around predictable alignments, independence can be unsettling.

Imran Khan’s story, therefore, is not merely about allegations or denial. It is about how sovereignty interacts with global power. He was not framed in those documents as morally compromised; he was framed as politically inconvenient. Whether that inconvenience contributed to his removal remains debated, but the documentary evidence confirms that it was noticed.

In the end, what set him apart was not scandal but stance. In a system accustomed to compliance, saying no can carry consequences. The documents do not resolve the debate over his ouster, but they illuminate the pressures surrounding it. And in doing so, they explain why, among many powerful names, one stood apart.

-

Europe News12 months ago

Europe News12 months agoChaos and unproven theories surround Tates’ release from Romania

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoTrump Expels Zelensky from the White House

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoTrump expands exemptions from Canada and Mexico tariffs

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoZelensky bruised but upbeat after diplomatic whirlwind

-

Art & Culture12 months ago

Art & Culture12 months agoThe Indian film showing the bride’s ‘humiliation’ in arranged marriage

-

Pakistan News8 months ago

Pakistan News8 months agoComprehensive Analysis Report-The Faranian National Conference on Maritime Affairs-By Kashif Firaz Ahmed

-

Art & Culture12 months ago

Art & Culture12 months agoInternational Agriculture Exhibition held in Paris

-

Politics12 months ago

Politics12 months agoUS cuts send South Africa’s HIV treatment ‘off a cliff’