Art & Culture

‘Her meaning contains multitudes’: Why the Statue of Liberty is at the heart of US culture wars

Controversy over an Amy Sherald painting of the Statue of Liberty reveals divides over US national symbols, joining debates that have centred on the statue since it was first unveiled.

So fixed is our focus on the radiant points of her spiky crown and the upward thrust of her flickering lamp, it is easy to miss altogether the shackles of human enslavement that Lady Liberty – who is at the centre of a fresh skirmish in the US’s accelerating culture wars – is busy trampling underfoot. Her meaning contains multitudes. It pulls her in many directions.

Messily inspired, as all great art is, by a mixture of sources – from the Roman goddess Libertas, to the Greek sun god Helios, to the multifaceted Egyptian goddess Isis (who fascinated the sculpture’s creator, the French artist Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi) – the Statue of Liberty seems hardwired for debate. She boldly embodies the one straightforward truth about cultural symbols: their truths are never straightforward.

From the moment the statue was unveiled in October 1886, it provoked criticism from both ends of the political spectrum

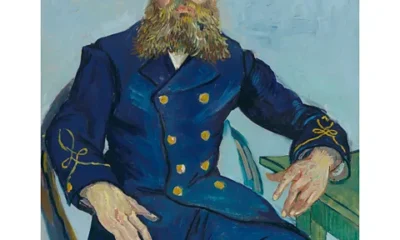

The current controversy over the essence of Bartholdi’s 46m (151ft)-tall copper sculpture, ingeniously engineered by Gustave Eiffel and formally presented to the United States as a gift from France on 4 July 1884, is a striking painting by African American contemporary artist Amy Sherald that reimagines the Statue of Liberty as a black transgender woman.

Earlier this month, Sherald, best known until now for her 2018 official portrait of First Lady Michelle Obama, was advised that her work, Trans Forming Liberty, might upset US President Donald Trump – who in January issued an Executive Order recognising two sexes only – male and female – and therefore should not be included in her upcoming exhibition at the federally funded Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. Rather than contemplate removing the work, Sherald decided to cancel the show altogether, citing “a culture of censorship”.

The Whitney Museum

The Whitney Museum

The contested work is currently on display at New York’s Whitney Museum as part of Sherald’s touring exhibition American Sublime and is characteristic of the artist’s instinct to dislocate her subjects and unsettle expectations. Sherald often achieves this, as she does both in her portrait of Obama and in Trans Forming Liberty, by translating her subjects’ complexions into an uncanny greyscale (or “grisaille”), nudging viewers to look past skin colour and reassess their assumptions about what constitutes race. The model for Sherald’s work, Arewà Basit, a black artist who identifies as non-binary trans-femme, is portrayed against a flat, periwinkle background, hand on hips, wearing a vibrant ultramarine gown that recalls the otherworldly resplendence of Renaissance Madonnas, and neon fuschia hair.

The torch she lifts has been supplanted by a clutch of humble Gerbera daisies, traditionally a symbol of joy and hope – a subtle subversion that faintly calls to mind the disarming weapon wielded by Banksy’s Flower Thrower, who too is powerful in his powerlessness. Of the intended potency of her own work, Sherald has explained that her painting “exists to hold space for someone whose humanity has been politicised and disregarded” – a sentiment that arguably rhymes with the hospitable spirit of the statue itself, which is famously affixed with a sonnet by Emma Lazarus, summoning “homeless, tempest-tossed” “masses yearning to breathe free”.

A polarising symbol

That synchronicity, however, may be both the painting’s profoundest allure and deepest liability. From the moment the statue was unveiled in October 1886, it provoked criticism from both ends of the political spectrum. Suffragettes insisted the sculpture’s depiction of a woman embodying liberty was too ironic to be taken seriously when women themselves were denied the right to vote. At the same time, conservatives objected to any incitement of migrants to flock to the US – those “huddled masses” the sculpture silently summons. By recasting Lady Liberty as a totem of unfulfilled promise, Sherald’s work aims to send a tremor down the fault-line of the American conscience.

Getty Images

Getty Images

While neither Trump nor anyone in his administration has, as yet, publicly condemned Sherald’s painting or its representation of a black transgender woman, the organisers of her scheduled exhibition, which was due to open on 19 September, had reason to fear imminent repercussions to its funding should the work go on display. In March, barely two months into his second term, Trump signed an Executive Order entitled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History”, which is aimed at curtailing financial support to museums and projects that, in its words, “degrade shared American values, divide Americans based on race, or promote programs or ideologies inconsistent with Federal law and policy”. Stating that the Smithsonian had “come under the influence of a divisive, race-centered ideology”, Trump instructed US Vice-President JD Vance to enforce his order. It was only a matter of time before Sherald’s recasting of Lady Liberty as black and transgender would catch Vance’s eye.

More like this:

• The real meaning of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers

• Who was the real Andy Warhol?

• The naked billboard that shocked the establishment

It was after meeting with Vance, who according to an anonymous source quoted by Fox News expressed concerns about the “woke” nature of Sherald’s work, that organisers of Sherald’s show began having second thoughts about including the painting in the exhibition – triggering the artist’s subsequent withdrawal from the project altogether. In recent months, enforcement of Trump’s Executive Order has intensified clashes over what kind of story the country’s symbols tell – or should be permitted to tell.

The exclusion of Sherald’s painting from public view has likely only amplified its exposure and impact. What’s more visible than something hidden?

Among the notable flashpoints is Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, home to the Liberty Bell. The White House has given the institution until the end of July 2025 to apply to all of its programmes a review to ensure that the narratives it projects “remind Americans of [the nation’s] extraordinary heritage, consistent progress toward becoming a more perfect Union, and unmatched record of advancing liberty, prosperity”. Particular issue has reportedly been taken with the Park’s inclusion in its displays of information relating to the ownership of slaves by America’s first President, George Washington, to the brutality that slaves suffered, and to the treatment of Native Americans.

Whatever is ultimately decided about the texture and tone of the exhibits at the Independence National Historical Park and of those at other federal museums and institutions now undertaking reviews, the resonance of cultural symbolism is difficult to control no matter how strenuously a government may try. Some bells can’t be unrung. Cracks remain. The exclusion of Sherald’s painting from public view has likely only amplified its exposure and impact. What’s more visible than something hidden?

As for Lady Liberty herself, Eiffel’s proleptic reliance when constructing the statue on a pliable wrought-iron pylon framework that functions like a network of springs, enabling the sculpture’s thin skin to flex and clench without breaking, has ensured the sculpture’s survival against the unpredictable buffets of time. Will the elastic meaning of liberty itself prove as resilient?

Amy Sherald’s exhibition American Sublime is at the Whitney Museum in New York City until 10 August.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Art & Culture

‘There’s no other poem like it’: Why this Robert Burns classic is a masterpiece

Tam O’Shanter is a rip-roaring tale of witches and alcohol, but it has hidden depths. On Burns Night this Sunday – and 235 years after the poem was published in 1791 – Scots everywhere may well be treated to a masterwork with a unique, universal appeal.

If you’re Scottish, or if you wish you were, then this Sunday is a red-letter day. Scotland’s greatest poet, Robert Burns, was born on 25 January 1759, and Burns Suppers are now held every year, all over the world, to mark his birthday. The guests drink whisky (not “whiskey”, please – that’s the Irish and US spelling), they eat haggis, tatties and neeps (don’t ask), and they hear some of the bard’s many ballads and poems. Ae Fond Kiss, To A Mouse and Auld Lang Syne are usually on the bill. And somebody may well recite Tam O’Shanter, a rip-roaring yarn about witchcraft and heavy drinking that was first published 235 years ago in 1791. It’s a poem that has even more to it than most Burns Supper regulars might realise.

“Tam O’Shanter is Burns’s masterpiece, it really is,” says Pauline Mackay, professor of Robert Burns studies and cultural heritage at the University of Glasgow. “It’s one of his most popular works, so when you say it’s your favourite Burns poem, people say, ‘Urgh, that’s so obvious’. But actually, I’ve been studying it for many, many years, and it’s so multifaceted. Burns brought all of his considerable talents to bear on capturing what inspires him, what motivates him, and his own perception of humanity and human nature.”

And that’s not all. Robert Irvine, the editor of Burns: Selected Poems and Songs, notes that there is a darkness to the poem that goes beyond its spine-tingling descriptions of the devil and his minions. “There’s some weird stuff going on there,” he says.

Most of the revellers are ‘rigwoodie hags’, but one witch, Nannie, is young, attractive and scantily clad

The poem tells the mock-heroic tale of Tam O’Shanter, a farmer who spends as much time drinking as he does working. At the end of one market day in Ayr, he retires to the pub with his “ancient, trusty, drouthy crony” Souter Johnnie (ie, Johnnie the shoemaker), never mind that his wife Kate is waiting at home. It’s only after hours of boozing and flirting with the landlady that Tam finally sets off on his horse, Maggie. But it’s a dark and stormy night, so he has to hold on to his hat, and sing songs to keep up his spirits. “Whiles holding fast his gude blue bonnet; / Whiles crooning o’er some auld Scots sonnet.” This reference to a “blue bonnet”, incidentally, is why beret-like flat hats with pom-poms are called Tam O’Shanters.

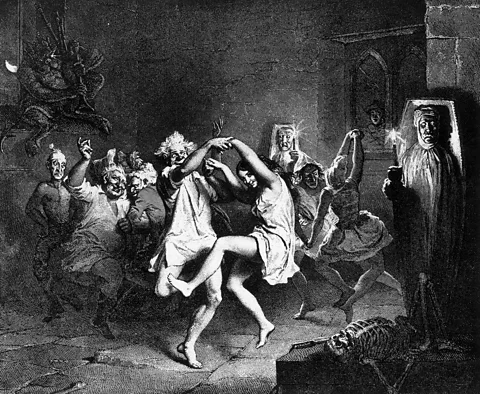

When he approaches Alloway’s Auld Kirk, Tam notices that a diabolical party is underway inside: witches and warlocks are dancing, and the devil himself, Auld Nick, is playing the bagpipes. Most of the revellers are “rigwoodie hags”, but one witch, Nannie, is so young, attractive and scantily clad that Tam yells out the only words he speaks in the poem: “Weel done, Cutty-sark!” This cat call would later lend its name to the Cutty Sark, a 19th-Century clipper ship that can be visited in Greenwich, London. Roughly translated, it means: “Well done, Short Dress!”

Nannie and her cohorts aren’t pleased to hear it: Tam has to flee on horseback with a crowd of screeching witches in hot pursuit, “Wi’ mony an eldritch skriech and hollo”. Luckily for him, witches can’t cross running water, and the River Doon is nearby. Tam manages to race over the bridge to safety, but Maggie the horse isn’t quite so fortunate. Nannie grabs hold of her tail just as she steps on to the Brig O’ Doon, and – spoiler alert – she is left with “scarce a stump”.

Rude jokes and chilling imagery

Carruthers calls it a “fairly hackneyed ghost story plot”, but the way Burns tells his story means that “there’s no other poem like it in Scottish literature”. Tam O’Shanter is “incredibly rich, so visual, so carefully crafted and so well-paced”, Mackay tells the BBC. “There’s just so much in there: everything from the way Burns has absorbed and assimilated the landscape and folklore of Ayrshire where he was born, and Dumfriesshire where he was writing the poem, to his keen interest in the supernatural, to the various comments that he makes on the complexities of human relationships and gender. All of this is so fascinating.”

There are lines in Scots, and others in English. There are rude jokes, and there is chillingly macabre imagery. There are tributes to the joys of getting drunk with friends in a cosy pub: “Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious. / O’er a’ the ills o’ life victorious!” And there are rueful philosophical musings on how transient those joys are: “But pleasures are like poppies spread, / You seize the flower, its bloom is shed.” Sometimes the narrator will address Tam himself: “O Tam, hadst thou but been sae wise, / As ta’en thou ain wife Kate’s advice!” At other times, he will address another character or the reader / listener – one reason, says Irvine, why the poem “lends itself to performance”, and has become a Burns Supper staple.

In fact, there isn’t much that Burns doesn’t do in Tam O’Shanter – and he does it all in rhyming iambic tetrameter. “He’s showing off,” says Irvine. “He’s doing one thing, and saying ‘Hey, look, I can do this other thing as well.’ In his first volume of poems, he does that between one poem and the next. He adopts different verse genres, he switches from Scots to English, he borrows from all sorts of different traditions – both what we think of now as the folk tradition, and the literary traditions of England and Scotland. It’s a virtuoso display of all the different things that he can do. And in Tam O’Shanter, he’s doing all that within one poem.”

Appropriately for a Burns Supper centrepiece, Tam O’Shanter is a feast, its most satisfying ingredient being its fond and insightful portrait of a character described as “the universal everyman” by Prof Gerard Carruthers, the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Robert Burns. Burns is admired for his egalitarian politics, and even in his rollicking horror comedy, his sympathy for the common man shines through. “Tam O’Shanter is a poem of misdirection,” Carruthers tells the BBC. “Burns is saying: ‘Look at this! Look at the witch! Look at the horse!’ Whereas in fact the real thing that he is talking about is the way in which we’re incorrigible as human beings.” The poem glows with “ridicule and affection at the same time for Tam, and by extension for the human psyche in general”.

It’s a poem about humanity – the pleasures and the appetites, the challenges and the frailties – Gerard Carruthers

Burns – a notorious womaniser – is especially sharp on masculine foibles. “Burns knows the male mind,” says Carruthers. “He knows that men in a lot of ways are stupid wee boys.” On the other hand, says Mackay, women may recognise themselves in Tam O’Shanter, too. “It’s a poem about humanity – the pleasures and the appetites, the challenges and the frailties – and I think that’s one of the reasons why Burns is so universally popular. He talks about what it is to be a human being – and everything that we see in different places throughout his poetic oeuvre is somehow represented in this one poem.”

Still, alongside its compassion, there is devilry of more than one kind in Tam O’Shanter. “The weird and disturbing thing about this poem is that Burns’s father, William Burnes, was a very pious and serious man who despaired of the libertine tendencies of his son,” says Irvine. “He organised repairs to Alloway Kirk when Burns and his brother were boys, and one of the reasons for that is that he wanted to be buried there – and he was. So, in 1784 Burns’s father was buried in Alloway churchyard, which Burns then makes famous as the site of a witches’ orgy. Was he getting revenge on his father for his disapproval of his eldest son?”

As well as everything else Burns is doing in Tam O’Shanter, it could be argued that he is almost literally dancing on his father’s grave. Anyone who hears it at a Burns Supper on Sunday will have plenty to chew on.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Art & Culture

Archaeological Seminar on Indus Valley Civilization of Pakistan in France

Paris ( Imran Y. CHOUDHRY):- The Embassy of Pakistan organized an event on the archeological studies of the 5000-year-old Indus Valley Civilization with Dr. Aurore Didier, Director of the French Archaeological Mission of the Indus Bassin.

Representatives of the UNESCO World Heritage Center, the Agha Khan Development Network (AKDN), archaeologists, historians and diplomats attended the event, which was organized with the support of the “Cercle des Amis du Pakistan”.

Dr. Didier briefed the audience on the history of the archeological excavations carried out by French archeologists in Pakistan. She gave an update on the latest research resulting from ten years of excavations at Chanhu-daro, one of the emblematic sites of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization. She also addressed how the adaptation of ancient populations to river and environmental fluctuations can be a key to understanding the current crises related to climate change and natural disasters that heavily impact South Asia today.

Addressing the audience, Ambassador Mumtaz Zahra Baloch noted the seventy years of cooperation between Pakistan and France in the domain of archeology. She appreciated the contributions made by the French Archeological Mission in Pakistan in research on the Indus Valley Civilization; and in promoting knowledge and competencies amongst local communities and scholars.

The Ambassador also reiterated her warm support for the “Cercle des Amis du Pakistan” for its initiatives in highlighting the cultural richness and diversity of Pakistan.

Art & Culture

From Bank Lines to Bus Seats: Bold Lessons in Courtesy, Courage, and Everyday Survival

In the line of bill payers at the bank,

As the fairer sex,

If sick, don’t just be blank

“Ladies first”, “excuse me11, “before you please.”

For deals with unpaid bills,

Ask for goods back, threat if you will,

Repeat the request for a job.

You may make it from the mob,

Instead of standing, share the seat on the bus

Isn’t it much better than making a fuss,

Whatever you do during tug-of-war, do not push the rope

Or you’ll be the laughing stock amidst cries of, “What a dope.”

-

Europe News11 months ago

Europe News11 months agoChaos and unproven theories surround Tates’ release from Romania

-

American News11 months ago

American News11 months agoTrump Expels Zelensky from the White House

-

American News11 months ago

American News11 months agoTrump expands exemptions from Canada and Mexico tariffs

-

American News11 months ago

American News11 months agoZelensky bruised but upbeat after diplomatic whirlwind

-

Art & Culture11 months ago

Art & Culture11 months agoThe Indian film showing the bride’s ‘humiliation’ in arranged marriage

-

Art & Culture11 months ago

Art & Culture11 months agoInternational Agriculture Exhibition held in Paris

-

Pakistan News7 months ago

Pakistan News7 months agoComprehensive Analysis Report-The Faranian National Conference on Maritime Affairs-By Kashif Firaz Ahmed

-

Politics11 months ago

Politics11 months agoUS cuts send South Africa’s HIV treatment ‘off a cliff’