Art & Culture

Andong’s Gwangsan Kim Clan Manuscript Suun Japbang: ‘Yukjjim’ Brings a 500-Year Culinary Tradition to London

— Special feature for the 2025 Hampton Court Palace Food Festival

LONDON/ANDONG — From 23 to 25 August 2025, the historic grounds of Hampton Court Palace will host a rare encounter with Korea’s early culinary scholarship as the classical cookbook Suun Japbang (需雲雜方) takes the stage in an official programme at the Hampton Court Palace Food Festival. During the festival, Head Housewife (Jongbu) Kim Do-eun of the Gwangsan Kim clan’s Seolwoldang head family in Andong will present a live demonstration of yukjjim, a braised-beef dish interpreted through the principles found in Suun Japbang, inviting European audiences to experience the essence of early-Joseon gastronomy.

A window on the Joseon kitchen: identity and significance of Suun Japbang

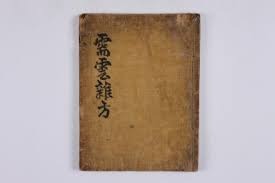

Compiled in the early 16th century by the Andong scholar Kim Yu (1491–1555) and later supplemented by his grandson Kim Ryeong (1577–1641), Suun Japbang is a two-volume, one-book manuscript in classical Chinese. It systematises 121 entries spanning brewing, jangs (fermented pastes and soy sauce), kimchi, soups, preservation and even seed sowing—an integrated record of the lifestyle, practical science and aesthetics of a literati household in early Joseon. Since coming to light in 1986, it has been recognised by the academy as one of the earliest extant Korean culinary texts.

Transmitted within the Gwangsan Kim clan of Yean, Andong, the manuscript is now entrusted to the Korean Studies Advancement Centre (Andong) and was designated a “Treasure” on 24 August 2021 under Korea’s national heritage system. The listing records it as a documentary heritage manuscript (one book, twenty-three folios), underscoring that this is far more than a family recipe notebook: it is a state-recognised record of cultural heritage.

The title itself is philosophically charged. “Suun” (需雲) invokes the I Ching’s Hexagram 5 (Xu), traditionally associated with the refined etiquette of eating, drinking and hosting; “Japbang” (雜方) means “various methods”. Together, they amount to a declaration of diverse, elevated culinary methods befitting a cultivated household.

Towards UNESCO Memory of the World

In February 2024, the City of Andong and the Korean Studies Advancement Centre convened a scholarly conference to place Suun Japbang and its companion text Eumsik Dimibang on a pathway to UNESCO’s Memory of the World register. Scholars assessed both works as documentary heritage, considering structure, content, cultural background and contemporary application, and announced a roadmap to publish English translations and distribute them to UNESCO-affiliated bodies.

The strategy is pragmatic: following domestic nomination, the partners intend to seek inscription first on the Asia-Pacific regional list (MOWCAP) in 2026, then progress to the international register — a staged approach designed to strengthen competitiveness in a crowded field.

For context, UNESCO’s Memory of the World programme catalogues humanity’s documentary heritage to promote preservation, accessibility and awareness. Inscription typically brings capacity-building, improved digital access and international visibility. In Korea, coordination among the National Heritage Authority, the Korean National Commission for UNESCO, local government and academia provides the institutional and diplomatic foundations required for a credible bid.

The government has also signalled an expansion of cooperative funding with UNESCO in 2025, a favourable tailwind for international promotion and partnerships around documentary heritage such as Suun Japbang.

“Hands of the head housewife, palates of the world”: spotlight on Kim Do-eun

Kim Do-eun, the 15th Jongbu (head housewife) of the Seolwoldang head family of the Gwangsan Kim clan, leads the Suun Japbang Traditional Food Experience Centre and has spent years translating classical recipes for the modern table. In 2013 she co-founded the Suun Japbang Research Institute to commercialise menus grounded in textual verification, and in 2015 showcased the potential of these 500-year-old recipes through a gala dinner at Seoul’s Michelin-starred La Yeon. Her modern readings of meat and soup preparations — notably Seoyeotang, which foregrounds Dioscorea opposita (Chinese yam) — have drawn critical attention.

She has often argued in interviews that authentic globalisation comes not by diluting tradition to suit foreign palates, but by allowing audiences to encounter the taste of tradition itself. Rooted in the Confucian ethos of ritual filial piety and hospitality (bongjesa jeopbingak), her philosophy animates documentary heritage as a living culture.

Her public engagement is vigorous. At the Andong Mask Dance Festival, the “Jongbu’s Kitchen” programme has attracted over 200 visitors per day, with the Suun Japbang chicken dish Jeon-gye-a proving especially popular. In 2025 she launched a contemporary Jeon-gye-a in collaboration with local restaurateurs — extending both textual translation and hands-on experience as twin wheels of Suun Japbang’s modern life.

Yukjjim in London: from manuscript to table

The centrepiece of the London appearance will be yukjjim. Drawing on the manuscript’s meat-cookery traditions — including lines of technique associated with jang-seasoned meats (“jangyuk”) and noodle-meat dishes (“yukmyeon”) — Kim will present a mature braise that marries soy-based seasoning, aromatics, controlled ageing and low-temperature braising. The aim is not merely to cook meat, but to express the depth of Korea’s fermented jangs while delivering peak texture.

According to the UK programme brief, Kim will demonstrate a modern articulation of yukjjim grounded in principles first recorded in Suun Japbang — translating the symbolism of the Jongbu, a traditional domestic authority, into a public culinary language. In Andong, the dish will prominently feature Andong Hanwoo (Korean native beef). Benefiting from the upper Nakdong River’s relatively dry climate and wide diurnal temperature range, Andong Hanwoo is prized for consistent marbling, resilient texture and a deep, lingering flavour — qualities that align naturally with yukjjim’s precisely judged braise.

Why London, and why now?

The Hampton Court Palace Food Festival, a signature event of the UK bank-holiday weekend, is a meeting-point of historic setting and contemporary gastronomy. Its royal-garden backdrop offers an optimal platform for Korea’s documentary gastronomy to converse directly with European culinary discourse. (Official hours for 2025: 10:00–18:00, 23–25 August.)

Andong, moreover, is a custodian city of the 2010 UNESCO World Heritage inscription “Historic Villages of Korea: Hahoe and Yangdong”. From seowon (Confucian academies), head-family ritual culture and seasonal customs to the culinary practices that supported them, the soil from which Suun Japbang emerged is dense with layered cultural strata. In London, yukjjim becomes the medium through which record and place speak in concert.

Prospects for UNESCO inscription and next steps

Experts cite several strengths: an unbroken transmission of a complete manuscript, rarity as an early private-household cookbook, a dense compendium of fermentation, preservation and health-nourishment knowledge, and a clear genealogical provenance within a single clan. If the 2024 conference roadmap — translation and annotated editions, international networks and staged MOWCAP-to-international inscription — proceeds as planned, observers judge the medium- to long-term prospects encouraging. Key hurdles will include demonstrating outstanding universal value, advancing preservation and access, and broad public engagement.

From a policy perspective, the outlook is constructive. With its 2021 designation as a national “Treasure”, Suun Japbang already stands on firm domestic ground, while the government’s widening of UNESCO-related cooperation funding creates a supportive environment for international advocacy. Priorities now include stabilised conservation and digital archiving, multi-language scholarly apparatus and outreach, and a management plan aligned to international review criteria.

Conclusion: a 500-year recipe, a diplomacy of today

Suun Japbang is both a document of knowledge born in a Joseon-era kitchen and, today, a language of cultural diplomacy at the world’s table. Kim Do-eun’s yukjjim is the terminus of a long journey and the opening sentence of the next. In the gardens of Hampton Court, a distinctly Korean grammar of taste — fermentation and restraint, season and ritual — will meet European sensibilities. The record stirs to life; the dish crosses borders. At the centre stands a book written five centuries ago: Suun Japbang.

Visitor information (for UK readers)

- Event: Hampton Court Palace Food Festival

- Dates: 23–25 August 2025, 10:00–18:00

- Venue: Hampton Court Palace, London

Special programme: “Suun Japbang Showcase” — live demonstration of yukjjim by Head Housewife Kim Do-eun and an introduction to Korea’s classical culinary texts.

Art & Culture

What’s the best way to learn a new language?

Krupa Padhy uncovers how we really learn foreign languages – in a dual challenge involving both Portuguese and Mandarin.

There was a time when my oversized hardback Collins Roberts French dictionary took pride of place on my bookshelf of my student accommodation. I owned an edition from the late 1980s, almost 1,000 pages long, handed down from my elder brothers. It travelled with me to Paris in the early 2000s, taking up half the space of my little case as a non-negotiable.

It was a sad day when a decade later, bursting at the seams of our one-bed flat with two babies, I decided it had to go. It had gathered dust since leaving university but had equally screamed that I had once been serious about language-learning.

Multilingualism has always been a part of my fabric. I was born into a Gujarati-speaking household, my Indian-origin parents having immigrated to the UK from Tanzania in the 1970s. My reading and writing skills were topped up with lessons at the local temple every Saturday as a kid. In 1995, Zee TV arrived in the UK on cable network, and I became hooked on watching cheesy Hindi serials every evening with the subtitles on. I took French to degree level and headed for my year abroad to Paris. Finally, a tinge of Spanish came to me after a few terms of evening classes. All these languages (bar the holiday-Spanish) have taken time and commitment.

Understandably maybe, I’ve reacted reluctantly to the countless advertisements on my Instagram feed promising to teach me a language in 30 days (if not sooner) by giving up less than 30 minutes a day.

The benefits of language-learning for our long-term brain health and happiness are well noted, so no regrets there. But had my four years of studying a language to degree level conjugating verbs and memorising vocabulary become an outdated way of learning? (Read more about the benefits of bilingualism here).

Along with the promise of becoming fluent at lightning speed, a range of new methods and technologies have transformed how we pick up languages in an increasingly time-poor age. One is “microlearning”, an approach that breaks down new information into small chunks that are meant to be absorbed quickly, sometimes within minutes or even seconds. It’s rooted in a concept known as the forgetting curve, which states that when people take in large amounts of information, they remember less of it over time.

In addition, there’s a wealth of new technologies, from chatbots offering instant feedback, to virtual reality and augmented reality technologies which drop you into conversations with virtual native speakers. However, some argue that the promise of fast fluency misses crucial elements of actually learning to speak to people in another language, such as developing cultural understanding and nuance.

So, with all this choice, what’s actually the best, science-backed way to learn a language? To find out, I teamed up with two researchers at Lancaster University’s Language Learning Lab: Patrick Rebuschat, a professor of linguistics and cognitive science, and Padraic Monaghan, a professor of cognition in the department of psychology. They let me try out an experiment they designed to mirror language-learning in the real world, and reveal how our brain picks up and makes sense of new words and sounds. The tasks basically simulate how we would cope if we were dropped into a foreign country with an unknown language, and just had to use our innate skills to figure out the new, mysterious sounds around us, and start to make sense of them.

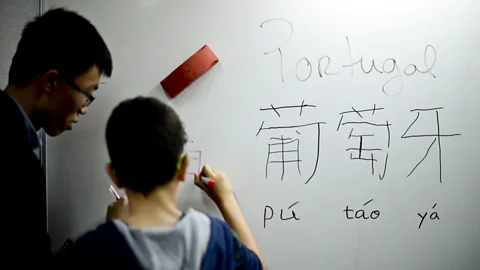

Having not learnt a language in two decades, I was about to learn some Mandarin and Portuguese. Over six days I would be spending just 30 minutes per day on the tasks and tests. I was to complete them, not ask any questions and wait until the end of the experiment for feedback.

Monaghan explains that such experimental studies are used to establish how people begin to get a foothold in a language.

I was intentionally not told from the outset what the tasks were about. But the researchers later explained that they were designed to activate my brain’s cross-situational learning (CSL) skills: that’s our natural, instinctive ability to use statistics to gradually work out the meanings of words and basic grammar. You can learn more about statistical learning in language acquisition here, but it is essentially our brain’s inherent ability to recognise patterns and regularities in speech (such as which words pair well with each other) based on the frequency of their use.

“People can learn very, very fast simply by keeping track of the statistics in the environment,” says Rebuschat. “This type of task is designed to mimic real-world learning under immersion settings, where things are often ambiguous and we rarely receive immediate feedback.”

Ahead of starting the experiment, I assumed that with my prior knowledge of French and basic Spanish, Portuguese would come naturally. Mandarin on the other hand was for me as foreign as a foreign language gets.

I’d also predicted that as I had done with most of my other languages, lesson one would comprise of basic greetings. Far from it.

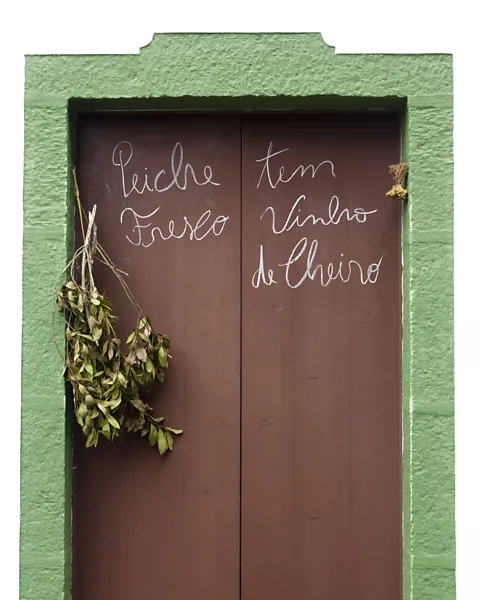

“If you were dropped into Portugal, Brazil, or another Portuguese-speaking country, the language you encounter would not unfold in a tidy pedagogical sequence starting with greetings,” explains Rebuschat. “Instead, you would hear a wide range of language in context: people ordering food in cafés, conversations on the street, a football commentary in the background.”

Thus, my exercise with Portuguese was to choose whether the word or sentence I was hearing matched one of two scenes, both featuring animated animals. This continued on repeat across three days, an example of statistical learning in action, says Rebuschat. “It is a basic learning ability that humans use from infancy – before infants know any language at all – to pick up patterns in the world around them. We use it to learn regularities in sounds, images, and events over time.”

I was quick to lean on my prior language knowledge. I know for example in Hindi saap means snake, and upon hearing the word sapo and seeing a frog on the screen, I matched the word to the image.

Soon after, I figured out that each noun appeared in both singular and plural forms performing one of four physical actions like pushing or pulling. The grammar was somewhat trickier but not unfamiliar from the French I had studied.

By day three of Portuguese, results showed my accuracy sat consistently between 90–100%, which I was told was higher than the typical English-speaking learner (presumably, because I was able to use those insights from my other languages). My brain was extracting meaning based on the frequency upon which the same nouns and verbs were appearing on screen.

My Mandarin learning journey started out somewhat differently.

As with Portuguese, I completed four short tasks and tests each day, but this time I was matching 12 incomprehensible sounds to images of 12 never-seen-before objects. As I later learnt, these weren’t real objects or real words. What I was saying out loud were in fact Mandarin tones, which are a core feature of the language as a different tone can change the meaning of a word.

Each made-up word was assigned to a specific object. Using artificial words, known as pseudowords, allows researchers to compare results and improvements fairly because students can’t draw on prior knowledge.

At times, repeating the same tones made me comatose and admittedly, I came to my answers with zero scientific reasoning. Lu-fah for example sounded like a loofah which I matched with an object that had soft spikes!

Linguistics students who are native speakers of Mandarin at Lancaster University looked at how I did. By the end of my first session matching the pseudoword to the right made-up object I had reached 75% accuracy, rising to 80% in sessions two and three.

My production test results (where I was asked to say the tone out aloud) were not as impressive, ranging from 38% rising to 55% by the third day, although I was reassured by Rebuschat that my scores were far above chance.

More like this:

• The language that doesn’t use ‘no’

• Why we can dream in more than one language

• How toddlers in Finland are saving an endangered Sámi language

Both Rebuschat and Monaghan concluded that I am in good possession of the building blocks needed to pick up languages well. These include having a good ear and being able to pick up subtle differences such as pronunciation, intonation and rhythm. My previous language-learning experience also helped me to recognise recurring patterns and features.

“A third factor, likely just as important as language-learning experience, is memory capacity,” Rebuschat tells me. “Unlike the Mandarin study, which used isolated pseudowords, the Portuguese CSL task required you to process and hold entire sentences in mind (determiners, nouns, verbs, number marking) while comparing them to two animated scenes. This places a substantial load on temporary storage, sequencing, and retrieval.”

Considering my decent report, would I be on course to learn at least one of these languages to a good standard in a matter of days?

“Achieving fluency in the real world requires sustained exposure, interaction, feedback, and social use over many months or years,” says Rebuschat.

He also points me in the direction of the US Defense Language Institute‘s Foreign Language Center, which provides some of the most intensive language training available. From Persian to Japanese, even with up to seven hours of learning per day plus homework, it takes around 64 weeks to reach basic professional proficiency.

In order to take my learning to the next level, the experts also make the case for traditional human instruction, something that is under threat at many schools and universities.

Rather than seeing new technologies as a threat to human teachers, Rebuschat considers them as complimentary, offering students additional practice and feedback, and widened access.

How else but through human interaction would I know that when my elders say ‘don’t drink my blood’ in Gujarati, they are asking me not to annoy them?

Monaghan also points out that learning to speak is one thing, but understanding what is said back to you is quite another.

“An interesting feature of language is that 70% of [a given] language is composed of just a few hundred words,” says Monaghan. “But what isn’t possible quickly is being able to understand what people say back to you, because they’ll be using those other, rarer words now and then.”

How else but through human-to-human interaction for example would I know that in Gujarati when my elders say “maru loi na pee” (“don’t drink my blood”) they are actually asking me not to annoy them? Or understand the practical phrase “ça a été” in French, which translates “as it has been”, but in conversation is one of the most versatile ways of expressing something was well?

Monaghan stresses that such intricacies throw into question some of the big promises made by new language learning technologies.

“It’s not going to replace that really high-level study of a language,” he says. “Being able to speak English and being able to read books in English doesn’t end studying English literature at university.” His words bring this nostalgic linguist some comfort. Whilst the dictionary may have gone, the yellowing copies of works by Jean-Paul Satre, Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire still have a safe space on my bookshelf for now.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Art & Culture

‘Fabled knights of old’: The true story of Japan’s mysterious samurai

From medieval beginnings, the samurai have inspired art, fiction and films, from Shōgun to Star Wars. But their true story is more complex and surprising than we might realise.

The enduring legacy of the samurai is a singular phenomenon in cultural history. No other medieval social group has been as celebrated or mythologised so relentlessly in popular culture – from ukiyo-e prints of the 18th Century to contemporary video games, TV shows and films.

The arc of fame always bends to falsification, and so it is with the samurai: were these fabled knights of old really as fearless, loyal, self-sacrificial, disciplined, and uniquely Japanese as we thought? Not according to the British Museum’s new Samurai exhibition, which wants to lift the smokescreen of fantasy around these mysterious and much misunderstood warriors – and reveal their true, and far more compelling, history.

So who were the samurai and how did their story begin? “They were not a unitary group of people, the same throughout history,” the exhibition’s curator Rosina Buckland tells the BBC. “I think the perception in the West is that samurai are warriors – and they certainly were. That’s how they emerged and rose to positions of power in the Middle Ages. But that’s not everything.”

The origins of the samurai lie in the 10th Century, when they were first recruited as mercenaries for the imperial courts. They gradually evolved into rural gentry, but they were not, as people tended to think of them later, gallant crusaders following time-honoured chivalric codes. In battle they tended to use opportunistic tactics like ambush and deception, and they were often motivated more by rewards of land and status than a sense of honour or selfless duty.

Their adaptive outlook meant that they also embraced multicultural influences and foreign technology – another surprising facet of samurai identity. The cuirass of a magnificent samurai suit of armour on display at the exhibition was based on a Portuguese design. It has a pointed front and angled sides to deflect musket bullets, features which only became necessary after the importation of European firearms into Japan in 1543.

‘Culture is power’

The samurai attained political power by exploiting the chaos caused by disputes over imperial succession. Eventually, one controlling clan – the Minamoto – took over and established a new government in 1185, parallel to the imperial court. Over the years, there was a rise and fall in these warlord dynasties involving various battles between clan leaders. But, as Buckland points out, “even in these early stages, culture is hugely important. Culture is power”.

Alongside being adept in the art of war, the samurai became conversant with the refined arts of painting, poetry, music performance, theatre and tea ceremonies

The military leaders – called Shōguns – realised that they couldn’t wield authority successfully with the outlook and mentality of tribal warlords. So, they found ways to supplement their military strength with the more subtle and sophisticated modes of power brokerage within courtly society.

Their playbook for statecraft was based on Chinese philosophy, principally the ideas of Confucius. “In Neo-Confucian thought,” says Buckland, “you have to have a balance between military power and cultural skill.” The ramification was increasing investment in soft power in the incense-infused chambers of the court.

Alongside being adept in the art of war, the samurai became conversant with the refined arts of painting, poetry, music performance, theatre and tea ceremonies. A fan depicting orchids, painted in the 19th Century by a samurai artist, is one of the more beautiful and unexpected items in the exhibition.

Shōgun, the Disney/FX series whose second season is currently in production, provides a fictionalised account of one of the turning points in samurai history. In the 1500s, one clan leader, Tokugawa Ieyasu (represented by the fictional Yoshii Toranaga in the series), established a government that was so successful it lasted for 250 years.

This meant that there were no more major battles within Japan, and the samurai took on new roles. Rather than marshalling the battlefield, they now managed the state. “They’re the ministers, the lawmakers, the tax collectors,” says Buckland. They took on jobs that percolated throughout the court, “right down to being the guards in the castle gates”.

Art & Culture

‘There’s no other poem like it’: Why this Robert Burns classic is a masterpiece

Tam O’Shanter is a rip-roaring tale of witches and alcohol, but it has hidden depths. On Burns Night this Sunday – and 235 years after the poem was published in 1791 – Scots everywhere may well be treated to a masterwork with a unique, universal appeal.

If you’re Scottish, or if you wish you were, then this Sunday is a red-letter day. Scotland’s greatest poet, Robert Burns, was born on 25 January 1759, and Burns Suppers are now held every year, all over the world, to mark his birthday. The guests drink whisky (not “whiskey”, please – that’s the Irish and US spelling), they eat haggis, tatties and neeps (don’t ask), and they hear some of the bard’s many ballads and poems. Ae Fond Kiss, To A Mouse and Auld Lang Syne are usually on the bill. And somebody may well recite Tam O’Shanter, a rip-roaring yarn about witchcraft and heavy drinking that was first published 235 years ago in 1791. It’s a poem that has even more to it than most Burns Supper regulars might realise.

“Tam O’Shanter is Burns’s masterpiece, it really is,” says Pauline Mackay, professor of Robert Burns studies and cultural heritage at the University of Glasgow. “It’s one of his most popular works, so when you say it’s your favourite Burns poem, people say, ‘Urgh, that’s so obvious’. But actually, I’ve been studying it for many, many years, and it’s so multifaceted. Burns brought all of his considerable talents to bear on capturing what inspires him, what motivates him, and his own perception of humanity and human nature.”

And that’s not all. Robert Irvine, the editor of Burns: Selected Poems and Songs, notes that there is a darkness to the poem that goes beyond its spine-tingling descriptions of the devil and his minions. “There’s some weird stuff going on there,” he says.

Most of the revellers are ‘rigwoodie hags’, but one witch, Nannie, is young, attractive and scantily clad

The poem tells the mock-heroic tale of Tam O’Shanter, a farmer who spends as much time drinking as he does working. At the end of one market day in Ayr, he retires to the pub with his “ancient, trusty, drouthy crony” Souter Johnnie (ie, Johnnie the shoemaker), never mind that his wife Kate is waiting at home. It’s only after hours of boozing and flirting with the landlady that Tam finally sets off on his horse, Maggie. But it’s a dark and stormy night, so he has to hold on to his hat, and sing songs to keep up his spirits. “Whiles holding fast his gude blue bonnet; / Whiles crooning o’er some auld Scots sonnet.” This reference to a “blue bonnet”, incidentally, is why beret-like flat hats with pom-poms are called Tam O’Shanters.

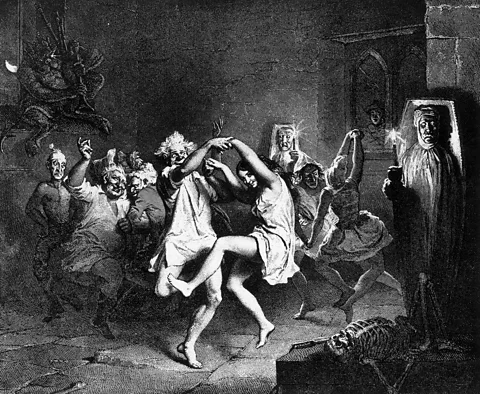

When he approaches Alloway’s Auld Kirk, Tam notices that a diabolical party is underway inside: witches and warlocks are dancing, and the devil himself, Auld Nick, is playing the bagpipes. Most of the revellers are “rigwoodie hags”, but one witch, Nannie, is so young, attractive and scantily clad that Tam yells out the only words he speaks in the poem: “Weel done, Cutty-sark!” This cat call would later lend its name to the Cutty Sark, a 19th-Century clipper ship that can be visited in Greenwich, London. Roughly translated, it means: “Well done, Short Dress!”

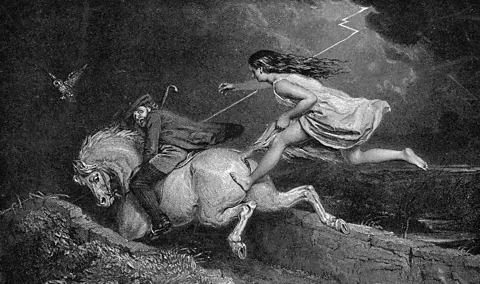

Nannie and her cohorts aren’t pleased to hear it: Tam has to flee on horseback with a crowd of screeching witches in hot pursuit, “Wi’ mony an eldritch skriech and hollo”. Luckily for him, witches can’t cross running water, and the River Doon is nearby. Tam manages to race over the bridge to safety, but Maggie the horse isn’t quite so fortunate. Nannie grabs hold of her tail just as she steps on to the Brig O’ Doon, and – spoiler alert – she is left with “scarce a stump”.

Rude jokes and chilling imagery

Carruthers calls it a “fairly hackneyed ghost story plot”, but the way Burns tells his story means that “there’s no other poem like it in Scottish literature”. Tam O’Shanter is “incredibly rich, so visual, so carefully crafted and so well-paced”, Mackay tells the BBC. “There’s just so much in there: everything from the way Burns has absorbed and assimilated the landscape and folklore of Ayrshire where he was born, and Dumfriesshire where he was writing the poem, to his keen interest in the supernatural, to the various comments that he makes on the complexities of human relationships and gender. All of this is so fascinating.”

There are lines in Scots, and others in English. There are rude jokes, and there is chillingly macabre imagery. There are tributes to the joys of getting drunk with friends in a cosy pub: “Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious. / O’er a’ the ills o’ life victorious!” And there are rueful philosophical musings on how transient those joys are: “But pleasures are like poppies spread, / You seize the flower, its bloom is shed.” Sometimes the narrator will address Tam himself: “O Tam, hadst thou but been sae wise, / As ta’en thou ain wife Kate’s advice!” At other times, he will address another character or the reader / listener – one reason, says Irvine, why the poem “lends itself to performance”, and has become a Burns Supper staple.

In fact, there isn’t much that Burns doesn’t do in Tam O’Shanter – and he does it all in rhyming iambic tetrameter. “He’s showing off,” says Irvine. “He’s doing one thing, and saying ‘Hey, look, I can do this other thing as well.’ In his first volume of poems, he does that between one poem and the next. He adopts different verse genres, he switches from Scots to English, he borrows from all sorts of different traditions – both what we think of now as the folk tradition, and the literary traditions of England and Scotland. It’s a virtuoso display of all the different things that he can do. And in Tam O’Shanter, he’s doing all that within one poem.”

Appropriately for a Burns Supper centrepiece, Tam O’Shanter is a feast, its most satisfying ingredient being its fond and insightful portrait of a character described as “the universal everyman” by Prof Gerard Carruthers, the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Robert Burns. Burns is admired for his egalitarian politics, and even in his rollicking horror comedy, his sympathy for the common man shines through. “Tam O’Shanter is a poem of misdirection,” Carruthers tells the BBC. “Burns is saying: ‘Look at this! Look at the witch! Look at the horse!’ Whereas in fact the real thing that he is talking about is the way in which we’re incorrigible as human beings.” The poem glows with “ridicule and affection at the same time for Tam, and by extension for the human psyche in general”.

It’s a poem about humanity – the pleasures and the appetites, the challenges and the frailties – Gerard Carruthers

Burns – a notorious womaniser – is especially sharp on masculine foibles. “Burns knows the male mind,” says Carruthers. “He knows that men in a lot of ways are stupid wee boys.” On the other hand, says Mackay, women may recognise themselves in Tam O’Shanter, too. “It’s a poem about humanity – the pleasures and the appetites, the challenges and the frailties – and I think that’s one of the reasons why Burns is so universally popular. He talks about what it is to be a human being – and everything that we see in different places throughout his poetic oeuvre is somehow represented in this one poem.”

Still, alongside its compassion, there is devilry of more than one kind in Tam O’Shanter. “The weird and disturbing thing about this poem is that Burns’s father, William Burnes, was a very pious and serious man who despaired of the libertine tendencies of his son,” says Irvine. “He organised repairs to Alloway Kirk when Burns and his brother were boys, and one of the reasons for that is that he wanted to be buried there – and he was. So, in 1784 Burns’s father was buried in Alloway churchyard, which Burns then makes famous as the site of a witches’ orgy. Was he getting revenge on his father for his disapproval of his eldest son?”

As well as everything else Burns is doing in Tam O’Shanter, it could be argued that he is almost literally dancing on his father’s grave. Anyone who hears it at a Burns Supper on Sunday will have plenty to chew on.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

-

Europe News12 months ago

Europe News12 months agoChaos and unproven theories surround Tates’ release from Romania

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoTrump Expels Zelensky from the White House

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoTrump expands exemptions from Canada and Mexico tariffs

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoZelensky bruised but upbeat after diplomatic whirlwind

-

Art & Culture12 months ago

Art & Culture12 months agoThe Indian film showing the bride’s ‘humiliation’ in arranged marriage

-

Pakistan News8 months ago

Pakistan News8 months agoComprehensive Analysis Report-The Faranian National Conference on Maritime Affairs-By Kashif Firaz Ahmed

-

Art & Culture12 months ago

Art & Culture12 months agoInternational Agriculture Exhibition held in Paris

-

Politics12 months ago

Politics12 months agoUS cuts send South Africa’s HIV treatment ‘off a cliff’