Art & Culture

‘A very deep bond of friendship’: The surprising story of Van Gogh’s guardian angel

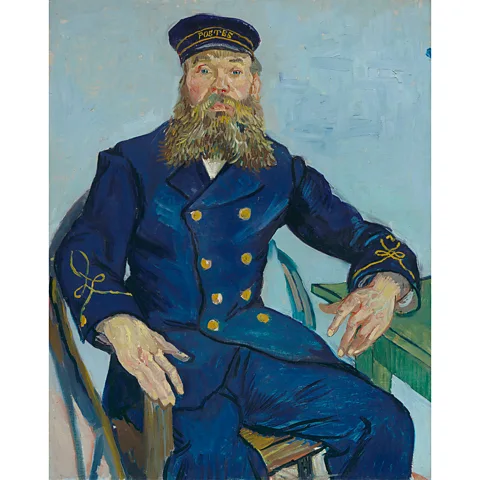

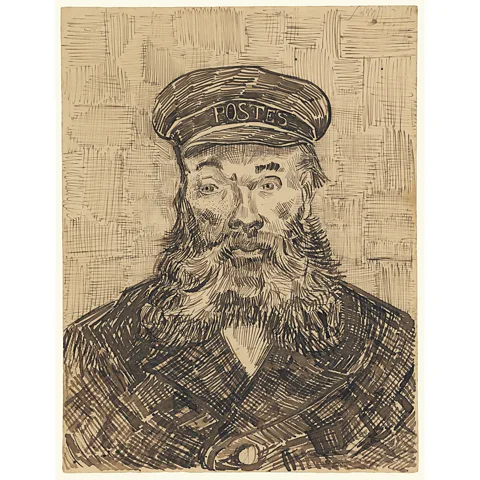

At the toughest, most turbulent time of his life, the Post-Impressionist painter was supported by an unlikely soulmate, Joseph Roulin, a postman in Arles. A new exhibition explores this close friendship, and how it benefited art history.

On 23 December, 1888, the day that Vincent van Gogh mutilated his ear and presented the severed portion to a sex worker, he was tended to by an unlikely soulmate: the postman Joseph Roulin.

A rare figure of stability during Van Gogh’s mentally turbulent two years in Arles, in the South of France, Roulin ensured that he received care in a psychiatric hospital, and visited him while he was there, writing to the artist’s brother Theo to update him on his condition. He paid Van Gogh’s rent while he was being cared for, and spent the entire day with him when he was discharged two weeks later. “Roulin… has a silent gravity and a tenderness for me as an old soldier might have for a young one,” Van Gogh wrote to Theo the following April, describing Roulin as “such a good soul and so wise and so full of feeling”.

Paying homage to this touching relationship is the exhibition Van Gogh: The Roulin Family Portraits, opening at the MFA Boston, USA, on 30 March, before moving on to its co-organiser, the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, in October. This is the first exhibition devoted to portraits of all five members of the Roulin family. It features more than 20 paintings by Van Gogh, alongside works by important influences on the Dutch artist, including 17th-Century Dutch masters Rembrandt and Frans Hals, and the French artist Paul Gauguin, who lived for two months with Van Gogh in Arles.

Roulin wasn’t just a model for Van Gogh – this was someone with whom he developed a very deep bond of friendship – Katie Hanson

“So much of what I was hoping for with this exhibition is a human story,” co-curator Katie Hanson (MFA Boston) tells the BBC. “The exhibition really highlights that Roulin isn’t just a model for him – this was someone with whom he developed a very deep bond of friendship.” Van Gogh’s tumultuous relationship with Gauguin, and the fallout between them that most likely precipitated the ear incident, has tended to overshadow his narrative, but Roulin offered something more constant and uncomplicated. We see this in the portraits – the open honesty with which he returns Van Gogh’s stare, and the mutual respect and affection that radiate from the canvas.

A new life in Arles

Van Gogh moved from Paris to Arles in February 1888, believing the brighter light and intense colours would better his art, and that southerners were “more artistic” in appearance, and ideal subjects to paint. Hanson emphasises Van Gogh’s “openness to possibility” at this time, and his feeling, still relatable today, of being a new face in town. “We don’t have to hit on our life’s work on our first try; we might also be seeking and searching for our next direction, our next place,” she says. And it’s in this spirit that Van Gogh, a newcomer with “a big heart“, welcomed new connections.

Before moving into the yellow house next door, now known so well inside and out, Van Gogh rented a room above the Café de la Gare. The bar was frequented by Joseph Roulin, who lived on the same street and worked at the nearby railway station supervising the loading and unloading of post. Feeling that his strength lay in portrait painting, but struggling to find people to pose for him, Van Gogh was delighted when the characterful postman, who drank a sizeable portion of his earnings at the café, agreed to pose for him, asking only to be paid in food and drink.

ADVERTISING

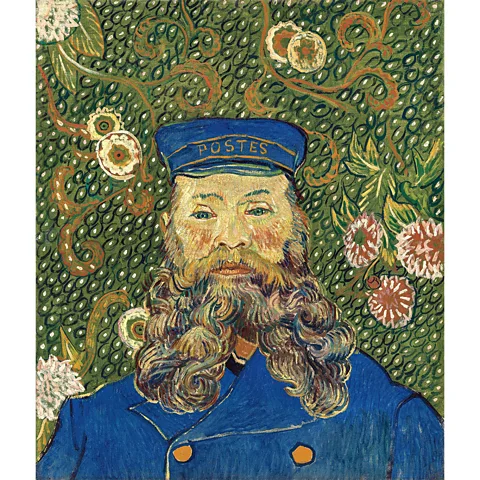

Between August 1888 and April 1889, Van Gogh made six portraits of Roulin, symbols of companionship and hope that contrast with the motifs of loneliness, despair and impending doom seen in some of his other works. In each, Roulin is dressed in his blue postal worker’s uniform, embellished with gold buttons and braid, the word “postes” proudly displayed on his cap. Roulin’s stubby nose and ruddy complexion, flushed with years of drinking, made him a fascinating muse for the painter, who described him as “a more interesting man than many people”.

Roulin was just 12 years older than Van Gogh, but he became a guiding light and father figure to the lonely painter – on account of Roulin’s generous beard and apparent wisdom, Van Gogh nicknamed him Socrates. Born into a wealthy family, Van Gogh belonged to a very different social class from Roulin, but was taken with his “strong peasant nature” and forbearance when times were hard. Roulin was a proud and garrulous republican, and when Van Gogh saw him singing La Marseillaise, he noticed how painterly he was, “like something out of Delacroix, out of Daumier”. He saw in him the spirit of the working man, describing his voice as possessing “a distant echo of the clarion of revolutionary France”.

The friendship soon opened the door to four further sitters: Roulin’s wife, Augustine, and their three children. We meet their 17-year-old son Armand, an apprentice blacksmith wearing the traces of his first facial hair, and appearing uneasy with the painter’s attention; his younger brother, 11-year-old schoolboy Camille, described in the exhibition catalogue as “squirming in his chair”; and Marcelle, the couple’s chubby-cheeked baby, who, Roulin writes, “makes the whole house happy”. Each painting represents a different stage of life, and each sitter was gifted their portrait. In total, Van Gogh created 26 portraits of the Roulins, a significant output for one family, rarely seen in art history.

Van Gogh had once hoped to be a father and husband himself, and his relationship with the Roulin family let him experience some of that joy. In a letter to Theo, he described Roulin playing with baby Marcelle: “It was touching to see him with his children on the last day, above all with the very little one when he made her laugh and bounce on his knees and sang for her.” Outside these walls, Van Gogh often experienced hostility from the locals, who described him as “the redheaded madman”, and even petitioned for his confinement. By contrast, the Roulins accepted his mental illness, and their home offered a place of safety and understanding.

The relationship, however, was far from one-sided. This educated visitor with his unusual Dutch accent was unlike anyone Roulin had ever met, and offered “a different kind of interaction”, explains Hanson. “He’s new in town, new to Roulin’s stories and he’s going to have new stories to tell.” Roulin enjoys offering advice – on furnishing the yellow house for example – and when, in the summer of 1888, Madame Roulin returned to her home town to deliver Marcelle, Roulin, left alone, found Van Gogh welcome company.

Roulin also got the rare opportunity to have portraits painted for free, and when, the following year, he was away for work in Marseille, it comforted him that baby Marcelle could still see his portrait hanging above her cradle. His fondness for Van Gogh shines through their correspondence. “Continue to take good care of yourself, follow the advice of your good Doctor and you will see your complete recovery to the satisfaction of your relatives and your friends,” he wrote to him from Marseille, signing off: “Marcelle sends you a big kiss.”

Van Gogh lived a further 19 months, producing a staggering 70 paintings in his last 70 days, and leaving one of art history’s most treasured legacies

Van Gogh’s portraits placed him in the heart of the family home. In his five versions of La Berceuse, meaning both “lullaby” and “the woman who rocks the cradle”, Mme Roulin held a string device, fashioned by Van Gogh, that rocked the baby’s cradle beyond the canvas, permitting the pair the peace to complete the artwork. The joyful background colours – green, blue, yellow or red – vary from one family member to another. Exuberant floral backdrops, reserved for the parents, come later, conveying happiness and affection – a blooming that took place since the earlier, plainer portraits.

Art history has also greatly benefitted from the freedom this relationship granted Van Gogh to experiment with portraiture, and to develop his own style with its delineated shapes, bold, glowing colours, and thick wavy strokes that make the forms vibrate with life. In the security of this friendship, he overturned the conventions of portrait painting, prioritising an emotional response to his subject, resolving “not to render what I have before my eyes” but to “express myself forcefully”, and to paint Roulin, he told Theo, “as I feel him”.

Had Van Gogh not felt Roulin’s unwavering support, he may not have survived the series of devastating breakdowns that began in December 1888 when he took a razor to his ear. With the care of those close to him, he lived a further 19 months, producing a staggering 70 paintings in his last 70 days, and leaving one of art history’s most treasured legacies.

Like the intimate portraits he created in Arles, the exhibition courses with optimism. “I hope being with these works of art and exploring his creative process – and his ways of creating connection – will be a heartwarming story,” Hanson says. Far from “shying away from the sadness” of this period of Van Gogh’s life, she says, the exhibition bears witness to the power of supportive relationships and “the reality that sadness and hope can coexist”.

Van Gogh: The Roulin Family Portraits is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston from 30 March to 7 September 2025, and at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam from 3 October 2025 to 11 January 2026.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.

Art & Culture

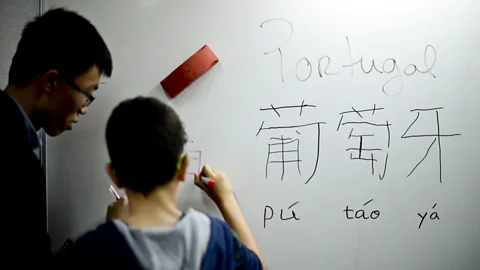

What’s the best way to learn a new language?

Krupa Padhy uncovers how we really learn foreign languages – in a dual challenge involving both Portuguese and Mandarin.

There was a time when my oversized hardback Collins Roberts French dictionary took pride of place on my bookshelf of my student accommodation. I owned an edition from the late 1980s, almost 1,000 pages long, handed down from my elder brothers. It travelled with me to Paris in the early 2000s, taking up half the space of my little case as a non-negotiable.

It was a sad day when a decade later, bursting at the seams of our one-bed flat with two babies, I decided it had to go. It had gathered dust since leaving university but had equally screamed that I had once been serious about language-learning.

Multilingualism has always been a part of my fabric. I was born into a Gujarati-speaking household, my Indian-origin parents having immigrated to the UK from Tanzania in the 1970s. My reading and writing skills were topped up with lessons at the local temple every Saturday as a kid. In 1995, Zee TV arrived in the UK on cable network, and I became hooked on watching cheesy Hindi serials every evening with the subtitles on. I took French to degree level and headed for my year abroad to Paris. Finally, a tinge of Spanish came to me after a few terms of evening classes. All these languages (bar the holiday-Spanish) have taken time and commitment.

Understandably maybe, I’ve reacted reluctantly to the countless advertisements on my Instagram feed promising to teach me a language in 30 days (if not sooner) by giving up less than 30 minutes a day.

The benefits of language-learning for our long-term brain health and happiness are well noted, so no regrets there. But had my four years of studying a language to degree level conjugating verbs and memorising vocabulary become an outdated way of learning? (Read more about the benefits of bilingualism here).

Along with the promise of becoming fluent at lightning speed, a range of new methods and technologies have transformed how we pick up languages in an increasingly time-poor age. One is “microlearning”, an approach that breaks down new information into small chunks that are meant to be absorbed quickly, sometimes within minutes or even seconds. It’s rooted in a concept known as the forgetting curve, which states that when people take in large amounts of information, they remember less of it over time.

In addition, there’s a wealth of new technologies, from chatbots offering instant feedback, to virtual reality and augmented reality technologies which drop you into conversations with virtual native speakers. However, some argue that the promise of fast fluency misses crucial elements of actually learning to speak to people in another language, such as developing cultural understanding and nuance.

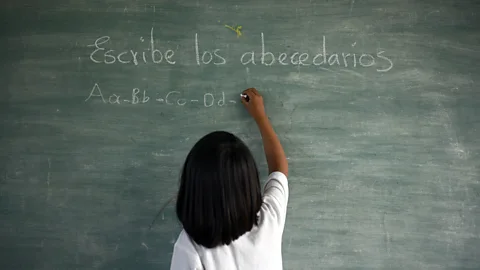

So, with all this choice, what’s actually the best, science-backed way to learn a language? To find out, I teamed up with two researchers at Lancaster University’s Language Learning Lab: Patrick Rebuschat, a professor of linguistics and cognitive science, and Padraic Monaghan, a professor of cognition in the department of psychology. They let me try out an experiment they designed to mirror language-learning in the real world, and reveal how our brain picks up and makes sense of new words and sounds. The tasks basically simulate how we would cope if we were dropped into a foreign country with an unknown language, and just had to use our innate skills to figure out the new, mysterious sounds around us, and start to make sense of them.

Having not learnt a language in two decades, I was about to learn some Mandarin and Portuguese. Over six days I would be spending just 30 minutes per day on the tasks and tests. I was to complete them, not ask any questions and wait until the end of the experiment for feedback.

Monaghan explains that such experimental studies are used to establish how people begin to get a foothold in a language.

I was intentionally not told from the outset what the tasks were about. But the researchers later explained that they were designed to activate my brain’s cross-situational learning (CSL) skills: that’s our natural, instinctive ability to use statistics to gradually work out the meanings of words and basic grammar. You can learn more about statistical learning in language acquisition here, but it is essentially our brain’s inherent ability to recognise patterns and regularities in speech (such as which words pair well with each other) based on the frequency of their use.

“People can learn very, very fast simply by keeping track of the statistics in the environment,” says Rebuschat. “This type of task is designed to mimic real-world learning under immersion settings, where things are often ambiguous and we rarely receive immediate feedback.”

Ahead of starting the experiment, I assumed that with my prior knowledge of French and basic Spanish, Portuguese would come naturally. Mandarin on the other hand was for me as foreign as a foreign language gets.

I’d also predicted that as I had done with most of my other languages, lesson one would comprise of basic greetings. Far from it.

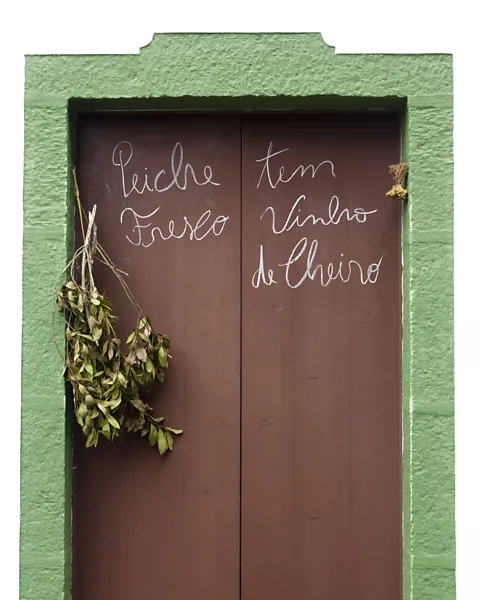

“If you were dropped into Portugal, Brazil, or another Portuguese-speaking country, the language you encounter would not unfold in a tidy pedagogical sequence starting with greetings,” explains Rebuschat. “Instead, you would hear a wide range of language in context: people ordering food in cafés, conversations on the street, a football commentary in the background.”

Thus, my exercise with Portuguese was to choose whether the word or sentence I was hearing matched one of two scenes, both featuring animated animals. This continued on repeat across three days, an example of statistical learning in action, says Rebuschat. “It is a basic learning ability that humans use from infancy – before infants know any language at all – to pick up patterns in the world around them. We use it to learn regularities in sounds, images, and events over time.”

I was quick to lean on my prior language knowledge. I know for example in Hindi saap means snake, and upon hearing the word sapo and seeing a frog on the screen, I matched the word to the image.

Soon after, I figured out that each noun appeared in both singular and plural forms performing one of four physical actions like pushing or pulling. The grammar was somewhat trickier but not unfamiliar from the French I had studied.

By day three of Portuguese, results showed my accuracy sat consistently between 90–100%, which I was told was higher than the typical English-speaking learner (presumably, because I was able to use those insights from my other languages). My brain was extracting meaning based on the frequency upon which the same nouns and verbs were appearing on screen.

My Mandarin learning journey started out somewhat differently.

As with Portuguese, I completed four short tasks and tests each day, but this time I was matching 12 incomprehensible sounds to images of 12 never-seen-before objects. As I later learnt, these weren’t real objects or real words. What I was saying out loud were in fact Mandarin tones, which are a core feature of the language as a different tone can change the meaning of a word.

Each made-up word was assigned to a specific object. Using artificial words, known as pseudowords, allows researchers to compare results and improvements fairly because students can’t draw on prior knowledge.

At times, repeating the same tones made me comatose and admittedly, I came to my answers with zero scientific reasoning. Lu-fah for example sounded like a loofah which I matched with an object that had soft spikes!

Linguistics students who are native speakers of Mandarin at Lancaster University looked at how I did. By the end of my first session matching the pseudoword to the right made-up object I had reached 75% accuracy, rising to 80% in sessions two and three.

My production test results (where I was asked to say the tone out aloud) were not as impressive, ranging from 38% rising to 55% by the third day, although I was reassured by Rebuschat that my scores were far above chance.

More like this:

• The language that doesn’t use ‘no’

• Why we can dream in more than one language

• How toddlers in Finland are saving an endangered Sámi language

Both Rebuschat and Monaghan concluded that I am in good possession of the building blocks needed to pick up languages well. These include having a good ear and being able to pick up subtle differences such as pronunciation, intonation and rhythm. My previous language-learning experience also helped me to recognise recurring patterns and features.

“A third factor, likely just as important as language-learning experience, is memory capacity,” Rebuschat tells me. “Unlike the Mandarin study, which used isolated pseudowords, the Portuguese CSL task required you to process and hold entire sentences in mind (determiners, nouns, verbs, number marking) while comparing them to two animated scenes. This places a substantial load on temporary storage, sequencing, and retrieval.”

Considering my decent report, would I be on course to learn at least one of these languages to a good standard in a matter of days?

“Achieving fluency in the real world requires sustained exposure, interaction, feedback, and social use over many months or years,” says Rebuschat.

He also points me in the direction of the US Defense Language Institute‘s Foreign Language Center, which provides some of the most intensive language training available. From Persian to Japanese, even with up to seven hours of learning per day plus homework, it takes around 64 weeks to reach basic professional proficiency.

In order to take my learning to the next level, the experts also make the case for traditional human instruction, something that is under threat at many schools and universities.

Rather than seeing new technologies as a threat to human teachers, Rebuschat considers them as complimentary, offering students additional practice and feedback, and widened access.

How else but through human interaction would I know that when my elders say ‘don’t drink my blood’ in Gujarati, they are asking me not to annoy them?

Monaghan also points out that learning to speak is one thing, but understanding what is said back to you is quite another.

“An interesting feature of language is that 70% of [a given] language is composed of just a few hundred words,” says Monaghan. “But what isn’t possible quickly is being able to understand what people say back to you, because they’ll be using those other, rarer words now and then.”

How else but through human-to-human interaction for example would I know that in Gujarati when my elders say “maru loi na pee” (“don’t drink my blood”) they are actually asking me not to annoy them? Or understand the practical phrase “ça a été” in French, which translates “as it has been”, but in conversation is one of the most versatile ways of expressing something was well?

Monaghan stresses that such intricacies throw into question some of the big promises made by new language learning technologies.

“It’s not going to replace that really high-level study of a language,” he says. “Being able to speak English and being able to read books in English doesn’t end studying English literature at university.” His words bring this nostalgic linguist some comfort. Whilst the dictionary may have gone, the yellowing copies of works by Jean-Paul Satre, Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire still have a safe space on my bookshelf for now.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Art & Culture

‘Fabled knights of old’: The true story of Japan’s mysterious samurai

From medieval beginnings, the samurai have inspired art, fiction and films, from Shōgun to Star Wars. But their true story is more complex and surprising than we might realise.

The enduring legacy of the samurai is a singular phenomenon in cultural history. No other medieval social group has been as celebrated or mythologised so relentlessly in popular culture – from ukiyo-e prints of the 18th Century to contemporary video games, TV shows and films.

The arc of fame always bends to falsification, and so it is with the samurai: were these fabled knights of old really as fearless, loyal, self-sacrificial, disciplined, and uniquely Japanese as we thought? Not according to the British Museum’s new Samurai exhibition, which wants to lift the smokescreen of fantasy around these mysterious and much misunderstood warriors – and reveal their true, and far more compelling, history.

So who were the samurai and how did their story begin? “They were not a unitary group of people, the same throughout history,” the exhibition’s curator Rosina Buckland tells the BBC. “I think the perception in the West is that samurai are warriors – and they certainly were. That’s how they emerged and rose to positions of power in the Middle Ages. But that’s not everything.”

The origins of the samurai lie in the 10th Century, when they were first recruited as mercenaries for the imperial courts. They gradually evolved into rural gentry, but they were not, as people tended to think of them later, gallant crusaders following time-honoured chivalric codes. In battle they tended to use opportunistic tactics like ambush and deception, and they were often motivated more by rewards of land and status than a sense of honour or selfless duty.

Their adaptive outlook meant that they also embraced multicultural influences and foreign technology – another surprising facet of samurai identity. The cuirass of a magnificent samurai suit of armour on display at the exhibition was based on a Portuguese design. It has a pointed front and angled sides to deflect musket bullets, features which only became necessary after the importation of European firearms into Japan in 1543.

‘Culture is power’

The samurai attained political power by exploiting the chaos caused by disputes over imperial succession. Eventually, one controlling clan – the Minamoto – took over and established a new government in 1185, parallel to the imperial court. Over the years, there was a rise and fall in these warlord dynasties involving various battles between clan leaders. But, as Buckland points out, “even in these early stages, culture is hugely important. Culture is power”.

Alongside being adept in the art of war, the samurai became conversant with the refined arts of painting, poetry, music performance, theatre and tea ceremonies

The military leaders – called Shōguns – realised that they couldn’t wield authority successfully with the outlook and mentality of tribal warlords. So, they found ways to supplement their military strength with the more subtle and sophisticated modes of power brokerage within courtly society.

Their playbook for statecraft was based on Chinese philosophy, principally the ideas of Confucius. “In Neo-Confucian thought,” says Buckland, “you have to have a balance between military power and cultural skill.” The ramification was increasing investment in soft power in the incense-infused chambers of the court.

Alongside being adept in the art of war, the samurai became conversant with the refined arts of painting, poetry, music performance, theatre and tea ceremonies. A fan depicting orchids, painted in the 19th Century by a samurai artist, is one of the more beautiful and unexpected items in the exhibition.

Shōgun, the Disney/FX series whose second season is currently in production, provides a fictionalised account of one of the turning points in samurai history. In the 1500s, one clan leader, Tokugawa Ieyasu (represented by the fictional Yoshii Toranaga in the series), established a government that was so successful it lasted for 250 years.

This meant that there were no more major battles within Japan, and the samurai took on new roles. Rather than marshalling the battlefield, they now managed the state. “They’re the ministers, the lawmakers, the tax collectors,” says Buckland. They took on jobs that percolated throughout the court, “right down to being the guards in the castle gates”.

Art & Culture

‘There’s no other poem like it’: Why this Robert Burns classic is a masterpiece

Tam O’Shanter is a rip-roaring tale of witches and alcohol, but it has hidden depths. On Burns Night this Sunday – and 235 years after the poem was published in 1791 – Scots everywhere may well be treated to a masterwork with a unique, universal appeal.

If you’re Scottish, or if you wish you were, then this Sunday is a red-letter day. Scotland’s greatest poet, Robert Burns, was born on 25 January 1759, and Burns Suppers are now held every year, all over the world, to mark his birthday. The guests drink whisky (not “whiskey”, please – that’s the Irish and US spelling), they eat haggis, tatties and neeps (don’t ask), and they hear some of the bard’s many ballads and poems. Ae Fond Kiss, To A Mouse and Auld Lang Syne are usually on the bill. And somebody may well recite Tam O’Shanter, a rip-roaring yarn about witchcraft and heavy drinking that was first published 235 years ago in 1791. It’s a poem that has even more to it than most Burns Supper regulars might realise.

“Tam O’Shanter is Burns’s masterpiece, it really is,” says Pauline Mackay, professor of Robert Burns studies and cultural heritage at the University of Glasgow. “It’s one of his most popular works, so when you say it’s your favourite Burns poem, people say, ‘Urgh, that’s so obvious’. But actually, I’ve been studying it for many, many years, and it’s so multifaceted. Burns brought all of his considerable talents to bear on capturing what inspires him, what motivates him, and his own perception of humanity and human nature.”

And that’s not all. Robert Irvine, the editor of Burns: Selected Poems and Songs, notes that there is a darkness to the poem that goes beyond its spine-tingling descriptions of the devil and his minions. “There’s some weird stuff going on there,” he says.

Most of the revellers are ‘rigwoodie hags’, but one witch, Nannie, is young, attractive and scantily clad

The poem tells the mock-heroic tale of Tam O’Shanter, a farmer who spends as much time drinking as he does working. At the end of one market day in Ayr, he retires to the pub with his “ancient, trusty, drouthy crony” Souter Johnnie (ie, Johnnie the shoemaker), never mind that his wife Kate is waiting at home. It’s only after hours of boozing and flirting with the landlady that Tam finally sets off on his horse, Maggie. But it’s a dark and stormy night, so he has to hold on to his hat, and sing songs to keep up his spirits. “Whiles holding fast his gude blue bonnet; / Whiles crooning o’er some auld Scots sonnet.” This reference to a “blue bonnet”, incidentally, is why beret-like flat hats with pom-poms are called Tam O’Shanters.

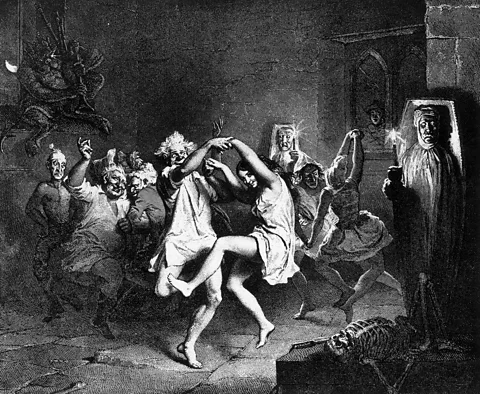

When he approaches Alloway’s Auld Kirk, Tam notices that a diabolical party is underway inside: witches and warlocks are dancing, and the devil himself, Auld Nick, is playing the bagpipes. Most of the revellers are “rigwoodie hags”, but one witch, Nannie, is so young, attractive and scantily clad that Tam yells out the only words he speaks in the poem: “Weel done, Cutty-sark!” This cat call would later lend its name to the Cutty Sark, a 19th-Century clipper ship that can be visited in Greenwich, London. Roughly translated, it means: “Well done, Short Dress!”

Nannie and her cohorts aren’t pleased to hear it: Tam has to flee on horseback with a crowd of screeching witches in hot pursuit, “Wi’ mony an eldritch skriech and hollo”. Luckily for him, witches can’t cross running water, and the River Doon is nearby. Tam manages to race over the bridge to safety, but Maggie the horse isn’t quite so fortunate. Nannie grabs hold of her tail just as she steps on to the Brig O’ Doon, and – spoiler alert – she is left with “scarce a stump”.

Rude jokes and chilling imagery

Carruthers calls it a “fairly hackneyed ghost story plot”, but the way Burns tells his story means that “there’s no other poem like it in Scottish literature”. Tam O’Shanter is “incredibly rich, so visual, so carefully crafted and so well-paced”, Mackay tells the BBC. “There’s just so much in there: everything from the way Burns has absorbed and assimilated the landscape and folklore of Ayrshire where he was born, and Dumfriesshire where he was writing the poem, to his keen interest in the supernatural, to the various comments that he makes on the complexities of human relationships and gender. All of this is so fascinating.”

There are lines in Scots, and others in English. There are rude jokes, and there is chillingly macabre imagery. There are tributes to the joys of getting drunk with friends in a cosy pub: “Kings may be blest, but Tam was glorious. / O’er a’ the ills o’ life victorious!” And there are rueful philosophical musings on how transient those joys are: “But pleasures are like poppies spread, / You seize the flower, its bloom is shed.” Sometimes the narrator will address Tam himself: “O Tam, hadst thou but been sae wise, / As ta’en thou ain wife Kate’s advice!” At other times, he will address another character or the reader / listener – one reason, says Irvine, why the poem “lends itself to performance”, and has become a Burns Supper staple.

In fact, there isn’t much that Burns doesn’t do in Tam O’Shanter – and he does it all in rhyming iambic tetrameter. “He’s showing off,” says Irvine. “He’s doing one thing, and saying ‘Hey, look, I can do this other thing as well.’ In his first volume of poems, he does that between one poem and the next. He adopts different verse genres, he switches from Scots to English, he borrows from all sorts of different traditions – both what we think of now as the folk tradition, and the literary traditions of England and Scotland. It’s a virtuoso display of all the different things that he can do. And in Tam O’Shanter, he’s doing all that within one poem.”

Appropriately for a Burns Supper centrepiece, Tam O’Shanter is a feast, its most satisfying ingredient being its fond and insightful portrait of a character described as “the universal everyman” by Prof Gerard Carruthers, the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Robert Burns. Burns is admired for his egalitarian politics, and even in his rollicking horror comedy, his sympathy for the common man shines through. “Tam O’Shanter is a poem of misdirection,” Carruthers tells the BBC. “Burns is saying: ‘Look at this! Look at the witch! Look at the horse!’ Whereas in fact the real thing that he is talking about is the way in which we’re incorrigible as human beings.” The poem glows with “ridicule and affection at the same time for Tam, and by extension for the human psyche in general”.

It’s a poem about humanity – the pleasures and the appetites, the challenges and the frailties – Gerard Carruthers

Burns – a notorious womaniser – is especially sharp on masculine foibles. “Burns knows the male mind,” says Carruthers. “He knows that men in a lot of ways are stupid wee boys.” On the other hand, says Mackay, women may recognise themselves in Tam O’Shanter, too. “It’s a poem about humanity – the pleasures and the appetites, the challenges and the frailties – and I think that’s one of the reasons why Burns is so universally popular. He talks about what it is to be a human being – and everything that we see in different places throughout his poetic oeuvre is somehow represented in this one poem.”

Still, alongside its compassion, there is devilry of more than one kind in Tam O’Shanter. “The weird and disturbing thing about this poem is that Burns’s father, William Burnes, was a very pious and serious man who despaired of the libertine tendencies of his son,” says Irvine. “He organised repairs to Alloway Kirk when Burns and his brother were boys, and one of the reasons for that is that he wanted to be buried there – and he was. So, in 1784 Burns’s father was buried in Alloway churchyard, which Burns then makes famous as the site of a witches’ orgy. Was he getting revenge on his father for his disapproval of his eldest son?”

As well as everything else Burns is doing in Tam O’Shanter, it could be argued that he is almost literally dancing on his father’s grave. Anyone who hears it at a Burns Supper on Sunday will have plenty to chew on.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

-

Europe News12 months ago

Europe News12 months agoChaos and unproven theories surround Tates’ release from Romania

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoTrump Expels Zelensky from the White House

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoTrump expands exemptions from Canada and Mexico tariffs

-

American News12 months ago

American News12 months agoZelensky bruised but upbeat after diplomatic whirlwind

-

Art & Culture12 months ago

Art & Culture12 months agoThe Indian film showing the bride’s ‘humiliation’ in arranged marriage

-

Pakistan News8 months ago

Pakistan News8 months agoComprehensive Analysis Report-The Faranian National Conference on Maritime Affairs-By Kashif Firaz Ahmed

-

Art & Culture12 months ago

Art & Culture12 months agoInternational Agriculture Exhibition held in Paris

-

Politics12 months ago

Politics12 months agoUS cuts send South Africa’s HIV treatment ‘off a cliff’