Art & Culture

‘A woman should cast off her shame together with her clothes’: What women in ancient times really thought about Relationships

A new book tells the history of the ancient world through women. Here author Daisy Dunn explores what they had to say about their own sexuality – flying in the face of misogynist male stereotypes.

According to Semonides of Amorgos, a male poet working in Greece in the 7th Century BC, there are 10 main kinds of women. There are women who are like pigs, because they prefer eating to cleaning; women who resemble foxes, as they are peculiarly observant; donkey-women, who are sexually promiscuous; dog-women, marked for their disobedience. There are stormy sea-women, greedy Earth-women, thieving weasel-women, lazy horse-women, unattractive ape-women, and – the one good kind – hard-working bee-women.

Of all the women described in this list, which pulsates with the misogyny of the time, those so-called sexually promiscuous “donkey-women” are perhaps the most mysterious.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Historical accounts from the ancient world tend to reveal the cloistered nature of women’s lives. In Greece, women were usually veiled in public, and in Rome, they had “guardians” (ordinarily their father or husband) to supervise their movements and handling of property. Was the concept of the lusty woman pure male fantasy? Or were women of the ancient world more interested in sex than is generally believed?

As I learned while researching my new book The Missing Thread, the first history of the ancient world to be written through women, we have to look hard if we want to uncover what women really thought about sex.

So far were ancient women from flinching at the sight of erotica that some were even buried with it

The vast majority of the surviving sources were written by men who were prone to exaggerate women’s sexual habits in one direction or the other. Some went to such lengths to emphasise a woman’s virtue that they made her seem almost saintly and inhuman. Others purposely presented women as sexually voracious as a means of blackening their characters. If we took these descriptions at face value, we would come to the conclusion that women in the ancient world were either all chaste, or sex-mad. Fortunately, it is possible to peer into the hearts of some classical women, who provide a far deeper view of female sexuality.

Confessions of infatuation

Looking to the same period as the poet quoted above, we encounter Sappho, who composed lyric poetry on the Greek island of Lesbos in the 7th Century BC. Gazing at a woman sitting talking to a man, Sappho documented the intense physical sensations she experienced – fluttering heart, faltering speech, fire through the veins, temporary blindness, ringing ears, cold sweat, trembling, pallor – all of which are familiar to anyone who’s ever fallen in lust. In another poem, Sappho described garlanding a woman with flowers and reminisced wistfully about how, on a soft bed, she would “quench [her] desire”. These are the confessions of a woman who understands the irrepressibility of infatuation.

Sappho’s poems are so fragmentary today that it can be difficult to read them accurately, but scholars have detected in one of the papyri a reference to “dildos”, known in Greek as olisboi. These were employed in fertility rituals in Greece, as well as for pleasure, and feature as such on a number of vase paintings. Later in Rome, too, phallic objects had a talisman-like quality. It would not have made sense for women to shy away from symbols that were believed to bring good luck.

Getty Images

Getty Images

So far were ancient women from flinching at the sight of erotica that some were even buried with it. In the period before Rome came to prominence, the highly skilled Etruscans dominated the Italian mainland and filled it with scenes of a romantic nature. Numerous works of art and pieces of tomb statuary depict men and women reclining together. An incense burner featuring men and women touching each other’s genitals was interred with an Etruscan woman in the 8th Century BC.

How prostitution was perceived

You only have to visit an ancient brothel, such as those of Pompeii, to see that sex was frequently on show. The walls of the dismal, cell-like rooms in which sex workers plied their trade are covered in graffiti, much of it written by male clients, who liked to comment on the performances of named women.

Historical accounts and speeches abound with descriptions of the hardships endured by such workers. Against Neaera, a prosecution speech delivered by Athenian politician Apollodorus in the 4th Century BC, provides particularly startling insight into the precariousness of these women’s lives. Just occasionally, however, we hear from a woman in touch with this world – and her words surprise.

In the 3rd Century BC, a female poet named Nossis living in the toe of Italy wrote in praise of an artwork and the fact that it was funded by a sex worker. A glorious statue of Aphrodite, goddess of sex and love, sung Nossis, had been erected in a temple using money raised by Polyarchis.

Polyarchis was not an anomaly. An earlier hetaera (courtesan or high-status sex worker) called Doricha used the money she had acquired similarly to purchase something for public view, in her case impressive spits for cooking oxen to be displayed at Delphi.

It was not sex these women embraced but rather the rare chance it afforded them to be remembered after they died. The vast majority of the women they knew were destined for anonymity.

Male writers’ insights

Male writers, for all their prejudices, can provide some of the most interesting insights into women and sex. In 411 BC, the comedian Aristophanes put on a play called Lysistrata, in which the women of Athens organise a sex strike in a bid to persuade their husbands to agree peace terms during the Peloponnesian War. This was a real conflict, waged between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies across three decades.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Many of the women in the play are less than pleased at having to give up their pleasure. They are made to conform to the donkey-woman stereotype for comic effect. There is a moment, however, at which the play turns in a serious direction and Aristophanes offers a more convincing female viewpoint.

The title character Lysistrata, who organises the strike, describes what it is really like for women in wartime. Not only are they banned from the Assembly, in which the war is discussed, but they are repeatedly bereaved. And while such a protracted conflict is hell for married women, it is still worse for unmarried women, who are deprived of the chance to marry altogether.

It was quite usual among the upper classes for marriages to be arranged – and a woman’s first experience of sex could be disorientating

While the men, Lysistrata points out, may return home from war grey-haired and still marry, the same does not hold true for virgins, many of whom will be deemed too old to wed and procreate. These lines convey the difference between the male and the female experience of war so accurately that it is tempting to believe that they reflect what women of the day were really saying.

We may find real women’s fears surrounding sex expressed in Greek tragedy too. Sophocles, the playwright most famous for Oedipus Rex, had a female character in his lost play Tereus describe what it is like to go from being a virgin to a wife. “And this, as soon as one night has yoked us,” utters Procne, a mythical queen, “we must commend and deem to be quite lovely”.

It was quite usual among the upper classes for marriages to be arranged. A woman’s first experience of sex could be as disorientating as Procne described.

Ancient sex tips

Women sometimes committed such thoughts to papyrus. In a letter attributed to her, Theano, a Greek female philosopher in the circle of Pythagoras (some say she was his wife), offers her friend Eurydice some timeless advice. A woman, she writes, should cast off her shame together with her clothes when she enters her husband’s bed. She can put both back on together as soon as she has stood up again.

Theano’s letter has come under scrutiny and may not be authentic. Nevertheless, it closely echoes what many women have said to each other in more modern times, and its advice seems to have been followed by women in the ancient world as well.

British Museum

British Museum

A certain Greek poet, Elephantis, was allegedly so keen to give women sex tips that she wrote her own short books on the topic. There is sadly no sign of her work today, but it is mentioned by both the Roman poet Martial and the Roman biographer and archivist Suetonius, who claimed that Emperor Tiberius (notorious for his sexual appetites) owned copies.

Where other women are quoted in other men’s writings, they tend to express themselves in terms of love as opposed to sex explicitly, which marks them out from some of their male contemporaries, including Martial and Catullus.

Lesbia, the pseudonymous lover of Catullus, tells him that “What a lady says to her lover in the moment / Ought to be written on the wind and running water”. The phrase “pillow talk” comes to mind.

Sulpicia, one of the few Roman poetesses whose verses survive, describes her misery at being in the countryside away from her lover Cerinthus on her birthday – and then her relief that she can be in Rome after all.

These women did not need to describe sex with their beloved in crude detail to reveal what they really thought of it. Men may dominate the sources but women, as Aphrodite well knew, could be every bit as passionate when the curtains were closed.

The Missing Thread: A New History of the Ancient World Through the Women Who Shaped It by Daisy Dunn has just been published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in the UK and will be published by Viking in the US on 30 July.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram

Art & Culture

Joy and Sorrow: A Reflection on Inequality and Human Connection by Zeenat Iqbal Hakimjee from Harmony

The begum dashes by in –

– Her flashing car,

To meet a companion at –

– A destination afar.

At a meeting point

In a parlour,

Five boys voraciously

In a corner ice Cream devour,

The silk saris and golden bangles

Glittering in the light,

The high heels and the leather purses

Presenting a sight;

The beggar in his torn

and tattered assemblage,

Spreads out his palm

And asks for patronage.

Art & Culture

“Confessions Beneath the Barrel” A city mourns as a poet captures the terror within a man’s own making—a chilling reflection on Karachi’s fractured heart.

Possessed by the devil,

I strode out to do evil.

With enmity written large on my face,

Somebody has to be dad in deaths embrace.

Just yesterday a child became an orphan,

And a couple were worried by the ransoms burden.

The fetters of depression behold the city,

Where everyday criminals like me enter captivity.

Karachi, Karachi of yore

Shall hot surface will not surface

Whilst I trigger my double barrel bore.

Art & Culture

‘A very deep bond of friendship’: The surprising story of Van Gogh’s guardian angel

At the toughest, most turbulent time of his life, the Post-Impressionist painter was supported by an unlikely soulmate, Joseph Roulin, a postman in Arles. A new exhibition explores this close friendship, and how it benefited art history.

On 23 December, 1888, the day that Vincent van Gogh mutilated his ear and presented the severed portion to a sex worker, he was tended to by an unlikely soulmate: the postman Joseph Roulin.

A rare figure of stability during Van Gogh’s mentally turbulent two years in Arles, in the South of France, Roulin ensured that he received care in a psychiatric hospital, and visited him while he was there, writing to the artist’s brother Theo to update him on his condition. He paid Van Gogh’s rent while he was being cared for, and spent the entire day with him when he was discharged two weeks later. “Roulin… has a silent gravity and a tenderness for me as an old soldier might have for a young one,” Van Gogh wrote to Theo the following April, describing Roulin as “such a good soul and so wise and so full of feeling”.

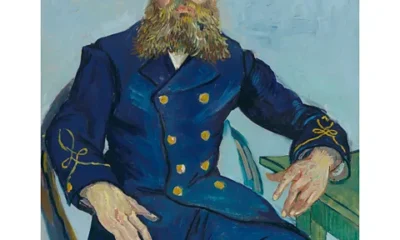

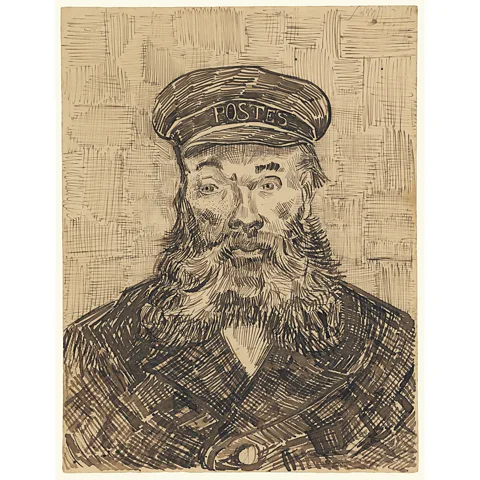

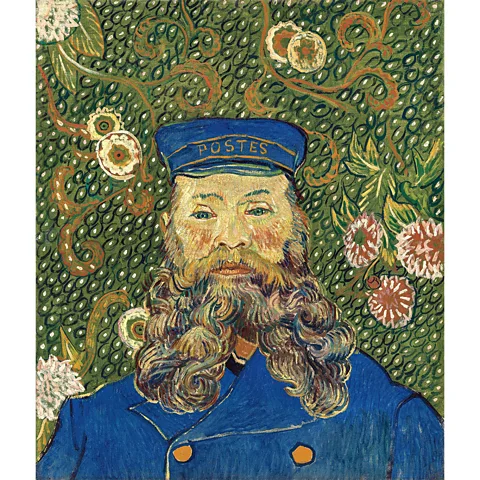

Paying homage to this touching relationship is the exhibition Van Gogh: The Roulin Family Portraits, opening at the MFA Boston, USA, on 30 March, before moving on to its co-organiser, the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, in October. This is the first exhibition devoted to portraits of all five members of the Roulin family. It features more than 20 paintings by Van Gogh, alongside works by important influences on the Dutch artist, including 17th-Century Dutch masters Rembrandt and Frans Hals, and the French artist Paul Gauguin, who lived for two months with Van Gogh in Arles.

Roulin wasn’t just a model for Van Gogh – this was someone with whom he developed a very deep bond of friendship – Katie Hanson

“So much of what I was hoping for with this exhibition is a human story,” co-curator Katie Hanson (MFA Boston) tells the BBC. “The exhibition really highlights that Roulin isn’t just a model for him – this was someone with whom he developed a very deep bond of friendship.” Van Gogh’s tumultuous relationship with Gauguin, and the fallout between them that most likely precipitated the ear incident, has tended to overshadow his narrative, but Roulin offered something more constant and uncomplicated. We see this in the portraits – the open honesty with which he returns Van Gogh’s stare, and the mutual respect and affection that radiate from the canvas.

A new life in Arles

Van Gogh moved from Paris to Arles in February 1888, believing the brighter light and intense colours would better his art, and that southerners were “more artistic” in appearance, and ideal subjects to paint. Hanson emphasises Van Gogh’s “openness to possibility” at this time, and his feeling, still relatable today, of being a new face in town. “We don’t have to hit on our life’s work on our first try; we might also be seeking and searching for our next direction, our next place,” she says. And it’s in this spirit that Van Gogh, a newcomer with “a big heart“, welcomed new connections.

Before moving into the yellow house next door, now known so well inside and out, Van Gogh rented a room above the Café de la Gare. The bar was frequented by Joseph Roulin, who lived on the same street and worked at the nearby railway station supervising the loading and unloading of post. Feeling that his strength lay in portrait painting, but struggling to find people to pose for him, Van Gogh was delighted when the characterful postman, who drank a sizeable portion of his earnings at the café, agreed to pose for him, asking only to be paid in food and drink.

ADVERTISING

Between August 1888 and April 1889, Van Gogh made six portraits of Roulin, symbols of companionship and hope that contrast with the motifs of loneliness, despair and impending doom seen in some of his other works. In each, Roulin is dressed in his blue postal worker’s uniform, embellished with gold buttons and braid, the word “postes” proudly displayed on his cap. Roulin’s stubby nose and ruddy complexion, flushed with years of drinking, made him a fascinating muse for the painter, who described him as “a more interesting man than many people”.

Roulin was just 12 years older than Van Gogh, but he became a guiding light and father figure to the lonely painter – on account of Roulin’s generous beard and apparent wisdom, Van Gogh nicknamed him Socrates. Born into a wealthy family, Van Gogh belonged to a very different social class from Roulin, but was taken with his “strong peasant nature” and forbearance when times were hard. Roulin was a proud and garrulous republican, and when Van Gogh saw him singing La Marseillaise, he noticed how painterly he was, “like something out of Delacroix, out of Daumier”. He saw in him the spirit of the working man, describing his voice as possessing “a distant echo of the clarion of revolutionary France”.

The friendship soon opened the door to four further sitters: Roulin’s wife, Augustine, and their three children. We meet their 17-year-old son Armand, an apprentice blacksmith wearing the traces of his first facial hair, and appearing uneasy with the painter’s attention; his younger brother, 11-year-old schoolboy Camille, described in the exhibition catalogue as “squirming in his chair”; and Marcelle, the couple’s chubby-cheeked baby, who, Roulin writes, “makes the whole house happy”. Each painting represents a different stage of life, and each sitter was gifted their portrait. In total, Van Gogh created 26 portraits of the Roulins, a significant output for one family, rarely seen in art history.

Van Gogh had once hoped to be a father and husband himself, and his relationship with the Roulin family let him experience some of that joy. In a letter to Theo, he described Roulin playing with baby Marcelle: “It was touching to see him with his children on the last day, above all with the very little one when he made her laugh and bounce on his knees and sang for her.” Outside these walls, Van Gogh often experienced hostility from the locals, who described him as “the redheaded madman”, and even petitioned for his confinement. By contrast, the Roulins accepted his mental illness, and their home offered a place of safety and understanding.

The relationship, however, was far from one-sided. This educated visitor with his unusual Dutch accent was unlike anyone Roulin had ever met, and offered “a different kind of interaction”, explains Hanson. “He’s new in town, new to Roulin’s stories and he’s going to have new stories to tell.” Roulin enjoys offering advice – on furnishing the yellow house for example – and when, in the summer of 1888, Madame Roulin returned to her home town to deliver Marcelle, Roulin, left alone, found Van Gogh welcome company.

Roulin also got the rare opportunity to have portraits painted for free, and when, the following year, he was away for work in Marseille, it comforted him that baby Marcelle could still see his portrait hanging above her cradle. His fondness for Van Gogh shines through their correspondence. “Continue to take good care of yourself, follow the advice of your good Doctor and you will see your complete recovery to the satisfaction of your relatives and your friends,” he wrote to him from Marseille, signing off: “Marcelle sends you a big kiss.”

Van Gogh lived a further 19 months, producing a staggering 70 paintings in his last 70 days, and leaving one of art history’s most treasured legacies

Van Gogh’s portraits placed him in the heart of the family home. In his five versions of La Berceuse, meaning both “lullaby” and “the woman who rocks the cradle”, Mme Roulin held a string device, fashioned by Van Gogh, that rocked the baby’s cradle beyond the canvas, permitting the pair the peace to complete the artwork. The joyful background colours – green, blue, yellow or red – vary from one family member to another. Exuberant floral backdrops, reserved for the parents, come later, conveying happiness and affection – a blooming that took place since the earlier, plainer portraits.

Art history has also greatly benefitted from the freedom this relationship granted Van Gogh to experiment with portraiture, and to develop his own style with its delineated shapes, bold, glowing colours, and thick wavy strokes that make the forms vibrate with life. In the security of this friendship, he overturned the conventions of portrait painting, prioritising an emotional response to his subject, resolving “not to render what I have before my eyes” but to “express myself forcefully”, and to paint Roulin, he told Theo, “as I feel him”.

Had Van Gogh not felt Roulin’s unwavering support, he may not have survived the series of devastating breakdowns that began in December 1888 when he took a razor to his ear. With the care of those close to him, he lived a further 19 months, producing a staggering 70 paintings in his last 70 days, and leaving one of art history’s most treasured legacies.

Like the intimate portraits he created in Arles, the exhibition courses with optimism. “I hope being with these works of art and exploring his creative process – and his ways of creating connection – will be a heartwarming story,” Hanson says. Far from “shying away from the sadness” of this period of Van Gogh’s life, she says, the exhibition bears witness to the power of supportive relationships and “the reality that sadness and hope can coexist”.

Van Gogh: The Roulin Family Portraits is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston from 30 March to 7 September 2025, and at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam from 3 October 2025 to 11 January 2026.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.

-

Europe News8 months ago

Europe News8 months agoChaos and unproven theories surround Tates’ release from Romania

-

American News8 months ago

American News8 months agoTrump Expels Zelensky from the White House

-

American News8 months ago

American News8 months agoTrump expands exemptions from Canada and Mexico tariffs

-

American News8 months ago

American News8 months agoZelensky bruised but upbeat after diplomatic whirlwind

-

Art & Culture8 months ago

Art & Culture8 months agoThe Indian film showing the bride’s ‘humiliation’ in arranged marriage

-

Art & Culture8 months ago

Art & Culture8 months agoInternational Agriculture Exhibition held in Paris

-

Politics8 months ago

Politics8 months agoUS cuts send South Africa’s HIV treatment ‘off a cliff’

-

Politics8 months ago

Politics8 months agoWorst violence in Syria since Assad fall as dozens killed in clashes