China

When China Becomes #1

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY) :- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : The United States is without question a great country. Its people are hardworking, intelligent, innovative, creative, and generous. From breakthroughs in medicine to technological revolutions in Silicon Valley, America has shaped the modern world in ways unmatched by any other nation. It remains a land where people from every nationality, race, and background are welcomed with open arms and provided with the opportunity to realize their dreams. Millions of immigrants, including myself, have experienced this spirit of hospitality and freedom, and this openness has helped make America a beacon of hope and aspiration for the entire world.

Yet today, the global balance of power is shifting rapidly, and the next two decades may define humanity’s political, economic, and technological future. At the heart of this transformation lies China, a country whose breathtaking rise over the last thirty years is unmatched in modern history and whose trajectory now threatens to challenge America’s position as the world’s leading power.

It is within this context that economists, think tanks, and policy experts around the world have debated when — and whether — China will overtake the United States as the dominant global power. The Council on Foreign Relations and Citigroup estimate that China could surpass the United States by 2035, driven by rapid technological advances, growing influence in international trade, and the vast economic ecosystem built around its Belt and Road Initiative. A report by the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR) places the crossing point around 2036 and predicts China may hold the top position for roughly two decades before the U.S. potentially regains its lead by 2057, underscoring that American decline is not inevitable if the right policies are adopted. Analysts at the RAND Corporation are more cautious, projecting that the tipping point may arrive only in the 2040s due to China’s aging population, rising debt, and slowing growth rates, but they warn that America’s relative decline accelerates if Washington fails to take decisive corrective measures. Meanwhile, The Guardian introduced the concept of “Peak China” in its 2025 economic report, suggesting that while China’s pace of expansion may eventually plateau, its technological leadership, military modernization, and deep integration with 154 countries give it an edge the United States cannot ignore. Despite differences in timelines, most credible institutions converge on one conclusion: the world is approaching a historic turning point where China could match or surpass American power, potentially redefining global leadership as early as the mid-2030s.

China’s leadership has spent decades investing heavily in its people, its industries, and its future. Millions of students were sent abroad with state support to acquire cutting-edge education and technical expertise, returning home to apply their skills to the country’s rapid technological advancement. Research centers and laboratories across the country are producing breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, quantum computing, electric vehicles, semiconductors, biotechnology, and space exploration. With consistent policy, centralized planning, and the ability to execute at extraordinary speed, China has achieved what no other country has attempted in modern times: it has built a knowledge-driven, innovation-focused economy at a scale the world has never seen before. Today, it competes directly with the United States in nearly every strategic sector, from energy to digital technology to defense.

This progress is matched by China’s deep global outreach through the Belt and Road Initiative, which now connects more than 154 nations through infrastructure, trade, and investment partnerships. By building ports, highways, railways, energy grids, and digital corridors across Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Europe, China has positioned itself at the center of emerging economic systems and established influence across continents. In doing so, it offers developing countries access to resources and opportunities while simultaneously expanding its own markets and soft power. Unlike coercive alliances built on dependence, Beijing presents this as a model of shared prosperity — one where growth is mutual and partnerships create new possibilities for all. This resonates deeply with many nations, especially those historically marginalized in the global economic order.

In contrast, the United States stands at a crossroads. For decades, America has been the center of global power, but over time, its overreliance on financial dominance rather than industrial capability has weakened its foundations. Much of its manufacturing base has been outsourced to China, India, Taiwan, Vietnam, Bangladesh, and other nations, leaving the U.S. dependent on foreign supply chains for critical products, including advanced electronics, pharmaceuticals, and energy systems. America’s global influence has long relied on the dominance of the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency, allowing it to print trillions without economic backing and finance its consumption and global strategy. Yet this advantage is eroding rapidly as BRICS nations, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and other blocs create new frameworks for trade that bypass the dollar entirely. As countries increasingly settle energy, technology, and agricultural trades in local currencies or the Chinese yuan, Washington’s ability to shape the world economy through financial leverage diminishes year after year.

Political polarization compounds these challenges. While China moves forward with a unified vision, the United States struggles to reconcile deep divisions between Democrats and Republicans, preventing the creation of long-term strategies needed to sustain global leadership. Powerful lobbying networks and foreign influence groups, such as AIPAC, steer U.S. policy to serve external interests rather than the nation’s strategic priorities. Meanwhile, traditional allies in Europe and Canada, as well as partners in Latin America, are pursuing greater independence from Washington, no longer willing to follow policies they increasingly view as contrary to their own interests. For many across the globe, America is still admired for its innovation, opportunity, and generosity, but there is growing frustration with its history of military interventions and regime-change policies that have destabilized nations from Iraq to Syria, from Libya to Afghanistan. If the United States wants to sustain its role as a respected leader, it must abandon strategies rooted in coercion and start building partnerships grounded in trust, friendship, and mutual respect.

Yet the United States is not destined to fall behind. It still holds immense strengths — from its culture of innovation and world-class universities to its entrepreneurial spirit and unparalleled capacity to attract global talent. America’s scientific leadership, vibrant democracy, and openness to diversity remain unmatched assets. But sustaining these advantages requires decisive action and renewed purpose.

To match China’s pace and reclaim long-term competitiveness, the U.S. must invest heavily in rebuilding its domestic manufacturing base, revitalizing its infrastructure, and restoring leadership in research and development. It must reform its education system to empower a new generation of engineers, scientists, and innovators, and it must foster unity in policymaking, setting aside partisanship for strategic national goals. Most critically, America must shift from a foreign policy based on dominance to one built on equal partnerships, cooperation, and mutual growth.

China’s rise represents a once-in-a-century transformation of the global order, and whether the coming decades lead to confrontation or collaboration will depend on choices made today. If Beijing sustains its momentum and continues integrating 154 nations into its economic vision, it could emerge as the defining power of the 21st century. But China also presents itself as a nation seeking harmony, offering development opportunities rather than pursuing domination, knowing that shared prosperity fuels its own progress. Meanwhile, the United States has the ability to remain a global leader, but only if it adapts to a rapidly changing world, invests in its people, strengthens its alliances, and treats all nations with dignity, fairness, and respect.

The world stands at the threshold of a profound transformation. America’s greatness lies in its creativity, diversity, and openness, qualities that have long inspired humanity. If it can harness these strengths, end destructive foreign interventions, and focus on building lasting partnerships based on trust and care, it can chart a new path where leadership is not imposed but earned. This is the moment for the United States to rediscover its founding ideals and become not just a superpower but a partner to the world. If it fails to do so, China’s relentless rise will reshape the global balance irreversibly, and the 21st century may well belong to Beijing. But if America chooses wisely, there is room for both nations to thrive, for a multipolar world rooted in cooperation rather than conflict, and for humanity to achieve shared prosperity.

China

Thai king becomes country’s first monarch to visit China

King Maha Vajiralongkorn of Thailand has arrived in China on Wednesday, the first ever visit by a reigning Thai monarch.

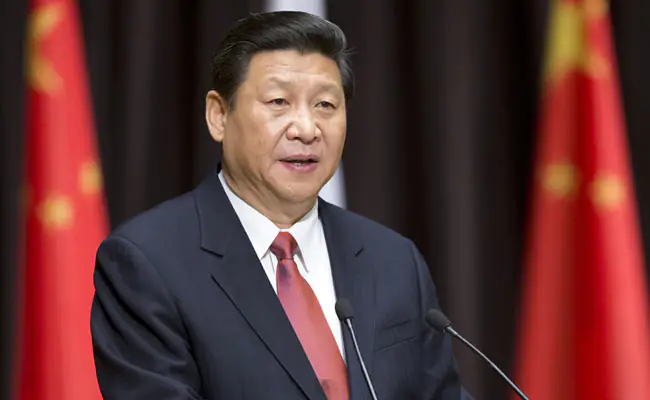

The visit is at the invitation of Chinese President Xi Jinping to celebrate the 50th anniversary of both countries establishing diplomatic ties for the first time in 1975. China is believed to have been pushing for this visit for some years.

The Thai government said in a statement that the trip “underlines the deep-rooted friendship and mutual understanding shared between Thailand and China at all levels”.

In Beijing, the king and his wife Queen Suthida will visit local landmarks like the Lingguang Buddhist Temple and the Beijing Aerospace City.

President Xi and his wife will also host a state banquet for the Thai royals.

This is the first major state visit by King Vajiralongkorn since he came to the throne nine years ago – in April he also made a trip to Bhutan. By contrast the most high-profile overseas trips made by his father King Bhumibol were to the United States in the 1960s, when Thailand was feted as a crucial Cold War partner, and a vital base for US military operations in Indochina.

Thailand is still officially a military ally of the US, but relations with China have grown steadily closer in recent years, while those with Washington have been frayed by US criticism of human rights in Thailand, by President Trump’s tariffs, and a perception that the US is no longer as committed as it once was to its Asian friends.

China is Thailand’s biggest trading partner, and increasingly a rival to the US as a source of military equipment.

Many Thais can trace their ancestry to migrants who came from China, and the Chinese government often highlights what it calls their “brotherly” or “family” relations.

The importance of those ties to Thailand was underlined earlier this year when the Thai authorities deported 40 Uyghur asylum-seekers back to China, in defiance of a warning not to do so by the US Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

Then in August an exhibition at Bangkok’s main arts centre featuring Uyghur and Tibetan artists was censored following complaints by Chinese diplomats.

The Thai government was spurred by Chinese pressure into taking action against scam compounds operating along its border with Myanmar, and objections by China are presumed to have been one of the factors which blocked a proposal to legalise casinos in Thailand.

Despite the lack of a Thai royal visit before this one, the Thai monarchy has played a significant role in sustaining Thai-Chinese relations through the work of the king’s younger sister, Princess Sirindhorn, who has studied Chinese art and language for the past 45 years, and been a frequent visitor to China.

China

How Beijing Reshaped the U.S. Tariff Regime

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY):- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : After months of tension, failures, and near breakdowns, the United States and China finally struck a landmark trade agreement that has reshaped the global balance of economic power. The negotiations culminated in Busan, South Korea, on October 30, 2025, where President Donald J. Trump and President Xi Jinping met face to face to seal a compromise that blended hard politics with pragmatic economics. What began as another episode in Trump’s “America First” campaign ended as a stunning reversal of Washington’s long-held trade strategy. For the first time in decades, the United States found itself negotiating not from a position of dominance, but parity—perhaps even vulnerability—with an economic rival that refused to bow to pressure.

The Busan summit produced an agreement that went far beyond tariff adjustments. It marked a recalibration of two superpowers’ economic engagement, with provisions covering tariff reductions, rare-earth exports, fentanyl-precursor chemicals, and agricultural trade. The outcome reflected necessity as much as diplomacy.

At the center of the breakthrough was a U.S. pledge to cut its combined tariff rate on Chinese imports from around 57 percent to approximately 47 percent, the first major rollback since Trump took over. The move signaled a pivot from confrontation to partial de-escalation and was hailed by economists as a lifeline for world trade.

In return, China suspended new restrictions on rare-earth mineral exports for at least one year, with an understanding that the suspension could be routinely extended. For Washington, this was no small concession. Rare earths—17 metallic elements critical to advanced technologies—form the backbone of America’s semiconductor, defense, and electric-vehicle industries. More than 70 percent of global production and 85 percent of refining capacity lie in Chinese hands, and when Beijing curbed exports in retaliation to earlier tariffs, it had paralyzed entire sectors of U.S. manufacturing. Restoring that supply flow was a strategic victory disguised as diplomacy.

Pressure on the White House had been mounting for months. Tech corporations and automakers warned of imminent shutdowns. The Pentagon privately admitted that major defense contractors depended on Chinese neodymium and dysprosium magnets for missile guidance and radar systems.

A U.S. Geological Survey report had cautioned that rebuilding a domestic supply chain could take up to ten years and cost more than $80 billion. Faced with that reality, Trump’s negotiators entered Busan with fewer cards than before, and Beijing knew it. Yet rather than triumphalism, China played its hand with deliberate restraint, focusing on pragmatism over posturing. Xi Jinping arrived at the summit not to lecture but to stabilize, projecting the tone of a statesman rather than a strategist of revenge.

Alongside the tariff cuts and rare-earth suspension came a surprising humanitarian dimension: a bilateral accord on fentanyl-precursor chemicals. China agreed to tighten monitoring of the compounds fueling America’s opioid epidemic, and in return, the U.S. halved its “fentanyl tariff” from 20 to 10 percent.

Xi also announced the resumption of large-scale Chinese purchases of American soybeans and other farm products, a symbolic win for U.S. farmers in the Midwest who had borne the brunt of earlier tariff wars. For Trump, that commitment provided domestic political relief; for Xi, it reaffirmed China’s leverage as the indispensable buyer in a fragile global food chain.

The meeting’s choreography reflected contrasting political cultures but a mutual understanding of necessity. Trump’s exuberant declaration that the talks were “twelve out of ten” was classic self-promotion, but analysts quickly noted the absence of concrete enforcement mechanisms. It was a deal built on goodwill and fatigue rather than trust.

Taiwan and semiconductor restrictions—particularly on the Nvidia Blackwell chip—were consciously excluded from discussion, a recognition that overloading the agenda could derail fragile progress. The leaders instead opted for a narrow corridor of cooperation, deferring confrontation to another day.

Another novel feature of the accord was its annual review mechanism, which replaced the rigidity of long-term treaties with a rolling, year-by-year renegotiation process. Rather than securing permanent peace, both sides built a framework of perpetual bargaining—flexible enough to adjust to political cycles yet risky enough to keep markets guessing.

It institutionalized uncertainty as the new normal, but also embedded the principle of dialogue into the heart of competition. For Trump, it ensured headlines and leverage; for Xi, it prevented the U.S. from dictating fixed terms that could constrain China’s long-term strategy. Both saw advantage in impermanence.

Markets reacted swiftly. The Baltic Dry Index stabilized, Pacific shipping surged, and global equities rose as investors sensed a return to predictability. The IMF projected a 0.4 percent boost to global GDP in 2026, primarily from revived trade flows and restored supply-chain continuity.

Analysts described the accord as a “pause, not peace.” It de-escalated the confrontation without resolving its causes. Beneath the smiles, the rivalry over technology, ideology, and global influence remained untouched. But Busan proved that rivalry need not mean rupture.

The deeper significance of the summit lay in what it revealed about the world’s economic transition. The age of laissez-faire globalization is fading. What emerged in Busan was the architecture of a managed economy—a hybrid system in which trade is weaponized yet indispensable, competitive yet cooperative.

America’s “America First” doctrine has evolved into “America Negotiates First,” while China’s “dual-circulation” model has shifted toward selective globalization. The WTO, once the arbiter of free trade, now stands eclipsed by the pragmatism of direct, leader-to-leader diplomacy. Every commodity—from semiconductors to soybeans—has become a bargaining chip in a global chess game where economic interdependence replaces ideology.

Yet the Busan accord also offered a rare glimpse of statesmanship amid rivalry. Xi Jinping’s calm assertion that “dialogue is better than confrontation” signaled a tactical but genuine openness. Trump, for his part, recognized—perhaps reluctantly—that economic coercion had reached its limits. Both leaders understood that in a world of intertwined supply chains, neither can thrive by isolating the other. The agreement thus stands as a testament not to friendship, but to realism: two adversaries choosing stability over escalation because chaos serves neither.

As the first container ships carrying newly authorized rare-earth cargoes departed Chinese ports, markets exhaled. The scene encapsulated the fragile peace that now defines global commerce—an uneasy equilibrium between competition and cooperation. The Busan agreement did not end the U.S.–China rivalry, but it transformed its character. It turned open confrontation into managed coexistence and replaced threats with transactions. The world may still be divided by politics, but it is bound by necessity. And in that necessity lies the quiet triumph of diplomacy over dominance—a reminder that in the twenty-first century, power belongs not to those who shout the loudest, but to those who can learn, at last, to deal.

China

From Poverty to Prosperity – Xinjiang’s Journey Through Time

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY) :- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : When the British flooded China with opium in the nineteenth century, they did not merely poison a people; they paralyzed a civilization. China’s national will was broken, its economy dismantled, and its sovereignty sold to foreign powers. The Communist Revolution of 1949 ended that humiliation, abolishing monarchy and feudal privilege and rebuilding the state on socialist foundations. Yet even after political liberation, the struggle against material poverty continued.

By the start of the 1980s, China’s western frontier—especially Xinjiang—remained trapped in deprivation. The province’s per-capita GDP hovered around ¥400 (≈ US $60), barely one-tenth of the national coastal average. Literacy was below 65 percent, life expectancy only 57–58 years, and infant mortality exceeded 60 per thousand births. Unemployment and under-employment surpassed 20 percent, and fewer than 30 percent of households had access to electricity or clean drinking water. Roads were sparse, hospitals were few, and higher education enrollment stood below 7 percent of eligible youth.

In this bleak landscape, Deng Xiaoping’s declaration—“Development is the hard truth”—became a national turning point. His leadership and the political will of the Communist Party re-anchored policy around one principle: China could not rise if its western half remained behind.

The 1980s therefore marked a deliberate beginning. The state poured investment into education and human development. Thousands of rural schools were built, teacher-training colleges expanded, and adult literacy drives reached even remote villages. Within a decade, literacy climbed to 82 percent, and life expectancy rose to 63 years. Agriculture was revitalized under the household-responsibility system, lifting grain and cotton yields by more than 40 percent. Rural health clinics and cooperative medical schemes began to extend basic care.

The 1990s concentrated on physical connectivity. Xinjiang’s first expressway linked Urumqi to Korla, rail lines stretched toward Kashgar, and irrigation projects converted deserts into farmland. Electricity production tripled, clean-water access passed 60 percent, and telephone coverage reached nearly all prefectures. The region’s GDP surpassed ¥1,200 (≈ US $180) per person. More importantly, mobility and market access dismantled isolation.

The 2000s saw industrial take-off under the Western Development Strategy. Energy pipelines, fertilizer and textile plants, and logistics parks emerged across the province. Vocational institutes trained tens of thousands of rural youth for skilled work. Per-capita income reached ¥8,000 (≈ US $1,200) by 2010, and the poverty rate plunged from over 40 percent in 2000 to below 15 percent by the decade’s end. Stable housing, paved roads, and rural electrification transformed living conditions.

The 2010s globalized the province. With the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Xinjiang became China’s western gateway. The Khorgos Dry Port on the Kazakh border evolved into one of the world’s busiest inland logistics hubs, handling more than six million tons of freight annually. Rail links to Europe shortened delivery times from 45 days to 12. Border trade centers, warehouses, and customs-free zones created tens of thousands of private jobs. Tourism and cultural industries flourished, turning local music, dance, and crafts into engines of pride and prosperity. By 2018, GDP per capita exceeded ¥35,000 (≈ US $5,000) and urbanization passed 60 percent.

The 2020s have anchored the shift from expansion to innovation. Xinjiang’s deserts now glitter with solar panels and wind turbines generating over 35 percent of regional electricity. Smart farming uses artificial intelligence, drones, and sensors to manage water in the Tarim Basin. IT parks in Urumqi and Changji host software and e-commerce firms; local universities partner with national institutes on artificial-intelligence and renewable-energy research. High-speed rail now links Urumqi to Lanzhou and Beijing, cutting travel to under 11 hours. Literacy exceeds 99 percent, life expectancy tops 75 years, and infant mortality has fallen below 6 per thousand. Per-capita income approaches ¥45,000 (≈ US $6,300), and unemployment has dropped below 5 percent—a forty-year reversal of fortune.

Behind this transformation stands unwavering political will. Each Five-Year Plan built upon the last, guided by a leadership that fused vision with accountability. The Cadre Performance Appraisal System required every village and county head to meet quantifiable targets—jobs created, infrastructure completed, educational gains achieved, and environmental standards maintained. Those who delivered rose; those who failed were replaced. This meritocracy of performance ensured continuity across generations.

During the author’s visits in 2012–2013 and again in 2024, the transformation was visible not only in concrete but in confidence. Modern highways sliced through once-barren landscapes. Border bazaars bustled with Central-Asian traders. IT students filled new university campuses. Families who once lived in mud-brick houses now owned cars, smartphones, and small businesses. The people’s dignity matched their development.

Comparing Xinjiang’s condition in 1980 with its remarkable transformation by 2025 reveals a story of unprecedented human progress. Literacy has surged from around 65 percent to over 99 percent, reflecting universal education and vocational training that empowered every generation. Life expectancy, once limited to about 58 years, now exceeds 75 years, thanks to modern healthcare, improved nutrition, and cleaner living conditions. Infant mortality, which stood at nearly 60 deaths per thousand births, has fallen to less than 6, marking one of the most dramatic improvements in public health anywhere in the developing world. Per-capita GDP has multiplied from a mere ¥400 to about ¥45,000, turning subsistence living into economic self-sufficiency. Unemployment has plummeted from roughly 20 percent to around 5 percent, while urbanization has nearly tripled—from 23 percent to 68 percent—bringing modern amenities and new opportunities to millions. Perhaps most symbolic of all, electricity access, which reached fewer than one-third of households in 1980, is now universal, illuminating every home and powering a new era of industrial, agricultural, and digital advancement.

Xinjiang’s story now transcends its borders. It offers a replicable model for nations still trapped in cycles of poverty and underdevelopment. The region demonstrates how to transform an unskilled population into a skilled, confident workforce through mass education and vocational training; how to turn formidable deserts into power-producing fields of solar and wind energy; how to bring greenery and agriculture to barren lands using modern irrigation and AI-driven precision farming; and how to elevate primitive bazaars into vibrant commercial centers and cross-border markets that drive regional trade. Xinjiang also illustrates the leap from subsistence agriculture to high-productivity agribusiness and from negligible industrial output to a thriving manufacturing base capable of meeting domestic demand and exporting abroad.

For developing nations in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the Xinjiang model provides a roadmap—a synthesis of political commitment, institutional accountability, human-capital development, and environmental innovation. With local adaptation, the same principles can raise any struggling region: empower people with education, equip them with skills, connect them through infrastructure, and sustain them with green technology.

From the forgotten deserts of 1980 to the dynamic economy of 2025, Xinjiang’s journey proves that prosperity is built, not bestowed—a triumph of will, work, and wisdom. Its transformation stands as living proof that visionary leadership, disciplined planning, and social investment can lift not just a province, but an entire civilization from poverty to pride.

-

Europe News9 months ago

Europe News9 months agoChaos and unproven theories surround Tates’ release from Romania

-

American News9 months ago

American News9 months agoTrump Expels Zelensky from the White House

-

American News9 months ago

American News9 months agoTrump expands exemptions from Canada and Mexico tariffs

-

American News9 months ago

American News9 months agoZelensky bruised but upbeat after diplomatic whirlwind

-

Art & Culture9 months ago

Art & Culture9 months agoThe Indian film showing the bride’s ‘humiliation’ in arranged marriage

-

Art & Culture9 months ago

Art & Culture9 months agoInternational Agriculture Exhibition held in Paris

-

Pakistan News5 months ago

Pakistan News5 months agoComprehensive Analysis Report-The Faranian National Conference on Maritime Affairs-By Kashif Firaz Ahmed

-

Politics9 months ago

Politics9 months agoUS cuts send South Africa’s HIV treatment ‘off a cliff’