American News

Migrant deported in chains: ‘No-one will go to US illegally now’

Gurpreet Singh was handcuffed, his legs shackled and a chain tied around his waist. He was led on to the tarmac in Texas by US Border Patrol, towards a waiting C-17 military transport aircraft.

It was 3 February and, after a months-long journey, he realised his dream of living in America was over. He was being deported back to India. “It felt like the ground was slipping away from underneath my feet,” he said.

Gurpreet, 39, was one of thousands of Indians in recent years to have spent their life savings and crossed continents to enter the US illegally through its southern border, as they sought to escape an unemployment crisis back home.

There are about 725,000 undocumented Indian immigrants in the US, the third largest group behind Mexicans and El Salvadoreans, according to the most recent figures from Pew Research in 2022.

Now Gurpreet has become one of the first undocumented Indians to be sent home since President Donald Trump took office, with a promise to make mass deportations a priority.

Gurpreet intended to make an asylum claim based on threats he said he had received in India, but – in line with an executive order from Trump to turn people away without granting them asylum hearings – he said he was removed without his case ever being considered.

About 3,700 Indians were sent back on charter and commercial flights during President Biden’s tenure, but recent images of detainees in chains under the Trump administration have sparked outrage in India.

US Border Patrol released the images in an online video with a bombastic choral soundtrack and the warning: “If you cross illegally, you will be removed.”

“We sat in handcuffs and shackles for more than 40 hours. Even women were bound the same way. Only the children were free,” Gurpreet told the BBC back in India. “We weren’t allowed to stand up. If we wanted to use the toilet, we were escorted by US forces, and just one of our handcuffs was taken off.”

Opposition parties protested in parliament, saying Indian deportees were given “inhuman and degrading treatment”. “There’s a lot of talk about how Prime Minister Modi and Mr Trump are good friends. Then why did Mr Modi allow this?” said Priyanka Gandhi Vadra, a key opposition leader.

Gurpreet said: “The Indian government should have said something on our behalf. They should have told the US to carry out the deportation the way it’s been done before, without the handcuffs and chains.”

An Indian foreign ministry spokesman said the government had raised these concerns with the US, and that as a result, on subsequent flights, women deportees were not handcuffed and shackled.

But on the ground, the intimidating images and President Trump’s rhetoric seem to be having the desired effect, at least in the immediate aftermath.

“No-one will try going to the US now through this illegal ‘donkey’ route while Trump is in power,” said Gurpreet.

In the longer term, this could depend on whether there are continued deportations, but for now many of the Indian people-smugglers, locally called “agents”, have gone into hiding, fearing raids against them by Indian police.

Gurpreet said Indian authorities demanded the number of the agent he had used when he landed back home, but the smuggler could no longer be reached.

“I don’t blame them, though. We were thirsty and went to the well. They didn’t come to us,” said Gurpreet.

While the official headline figure puts the unemployment rate at only 3.2%, it conceals a more precarious picture for many Indians. Only 22% of workers have regular salaries, the majority are self-employed and nearly a fifth are “unpaid helpers”, including women working in family businesses.

“We leave India only because we are compelled to. If I got a job which paid me even 30,000 rupees (£270/$340) a month, my family would get by. I would never have thought of leaving,” said Gurpreet, who has a wife, a mother and an 18-month-old baby to look after.

“You can say whatever you want about the economy on paper, but you need to see the reality on the ground. There are no opportunities here for us to work or run a business.”

Gupreet’s trucking company was among the cash-dependent small businesses that were badly hit when the Indian government withdrew 86% of the currency in circulation with four hours notice. He said he didn’t get paid by his clients, and had no money to keep the business afloat. Another small business he set up, managing logistics for other companies, also failed because of the Covid lockdown, he said.

He said he tried to get visas to go to Canada and the UK, but his applications were rejected.

Then he took all his savings, sold a plot of land he owned, and borrowed money from relatives to put together 4 million rupees ($45,000/£36,000) to pay a smuggler to organise his journey, Gurpreet told us.

On 28 August 2024, he flew from India to Guyana in South America to start an arduous journey to the US.

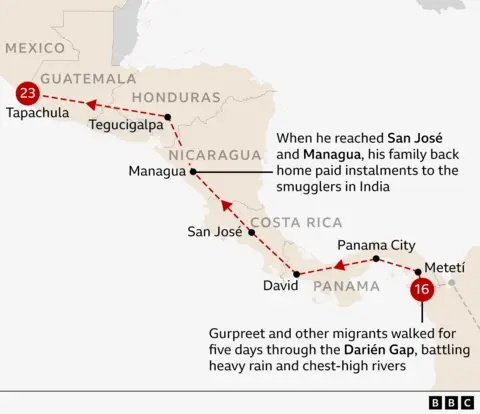

Gurpreet pointed out all the stops he made on a map on his phone. From Guyana he travelled through Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia, mostly by buses and cars, partly by boat, and briefly on a plane – handed from one people-smuggler to another, detained and released by authorities a few times along the way.

From Colombia, smugglers tried to get him a flight to Mexico, so he could avoid crossing the dreaded Darién Gap. But Colombian immigration didn’t allow him to board the flight, so he had to make a dangerous trek through the jungle.

A dense expanse of rainforest between Colombia and Panama, the Darién Gap can only be crossed on foot, risking accidents, disease and attacks by criminal gangs. Last year, 50 people died making the crossing.

“I was not scared. I’ve been a sportsman so I thought I would be OK. But it was the toughest section,” said Gurpreet. “We walked for five days through jungles and rivers. In many parts, while wading through the river, the water came up to my chest.”

Each group was accompanied by a smuggler – or a “donker” as Gurpreet and other migrants refer to them, a word seemingly derived from the term “donkey route” used for illegal migration journeys.

At night they would pitch tents in the jungle, eat a bit of food they were carrying and try to rest.

“It was raining all the days we were there. We were drenched to our bones,” he said. They were guided over three mountains in their first two days. After that, he said they had to follow a route marked out in blue plastic bags tied to trees by the smugglers.

“My feet had begun to feel like lead. My toenails were cracked, and the palms of my hands were peeled off and had thorns in them. Still, we were lucky we didn’t encounter any robbers.”

When they reached Panama, Gurpreet said he and about 150 others were detained by border officials in a cramped jail-like centre. After 20 days, they were released, he said, and from there it took him more than a month to reach Mexico, passing through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala.

Gurpreet said they waited for nearly a month in Mexico until there was an opportunity to cross the border into the US near San Diego.

“We didn’t scale a wall. There is a mountain near it which we climbed over. And there’s a razor wire which the donker cut through,” he said.

Gurpreet entered the US on 15 January, five days before President Trump took office – believing that he had made it just in time, before the borders became impenetrable and rules became tighter.

Once in San Diego, he surrendered to US Border Patrol, and was then detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

During the Biden administration, illegal or undocumented migrants would appear before an immigration officer who would do a preliminary interview to determine if each person had a case for asylum. While a majority of Indians migrated out of economic necessity, some also left fearing persecution because of their religious or social backgrounds, or their sexual orientation.

If they cleared the interview, they were released, pending a decision on granting asylum from an immigration judge. The process would often take years, but they were allowed to remain in the US in the meantime.

This is what Gurpreet thought would happen to him. He had planned to find work at a grocery store and then to get into trucking, a business he is familiar with.

Instead, less than three weeks after he entered the US, he found himself being led towards that C-17 plane and going back to where he started.

In their small house in Sultanpur Lodhi, a city in the northern state of Punjab, Gurpreet is now trying to find work to repay the money he owes, and fend for his family.

Additional reporting by Aakriti Thapar

Taken From BBC News

American News

Trump’s Naval Push Toward Iran

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY) :- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : President Donald Trump’s casual but chilling reference to an “armada” of U.S. warships heading toward the Middle East has once again pulled the world into a familiar but deeply unsettling theater of power, pressure, and peril. Speaking aboard Air Force One, he framed the movement of naval force as a precaution—“just in case”—while pointing to what he called a “good sign” that Iran had paused the hanging of protesters. Yet behind this language of conditional restraint lies a strategic pattern that many across the developing world, and especially in the Middle East, recognize all too well: the choreography of threat, softening, and sudden strike.

The USS Abraham Lincoln carrier strike group, with its five thousand sailors, squadrons of fighter jets, electronic attack aircraft, and escort ships, was already moving through the Indian Ocean as Trump spoke. It will soon join destroyers and littoral combat ships in a region that has rarely gone long without a U.S. aircraft carrier patrolling its waters. The official justification is deterrence—ensuring Iran does not escalate its response to mass protests that erupted in late December over worsening economic conditions.

There is a deeply rooted memory, especially in countries that have lived through the consequences of great-power intervention, of how negotiations and reassuring rhetoric can unfold alongside active military preparation. In Pakistan’s case, assurances were once delivered at the highest levels even as U.S. forces were already in motion—American cruise missiles crossed Pakistani airspace and struck targets inside Afghanistan, despite parallel diplomatic engagements and the presence of senior U.S. generals in Islamabad offering guarantees that Pakistan’s territorial integrity would not be violated. A similar pattern, in this view, emerged during periods when Iran was engaged in nuclear negotiations and discussions over its regional role, only to face sudden, precision strikes against sensitive military and nuclear-related sites under the cover of diplomatic dialogue. For many in the region, these episodes have fused into a collective perception that threats, softening gestures, and sudden force are not separate phases, but part of a single strategic sequence—one designed to lower vigilance before the moment of decisive action.

This is why Trump’s “armada” comment resonates far beyond Washington or Tehran. It revives fears of a scenario in which the visible calming of tensions becomes the prelude to a more devastating escalation. The strategic geography makes those fears sharper. The Middle East is not just a battlefield of ideologies and alliances; it is the heart of the global energy system. The Strait of Hormuz, a narrow maritime artery through which a significant share of the world’s oil supply passes, lies within the range of any serious confrontation between the United States, Iran, and their respective allies.

From a military perspective, the asymmetry of power is stark. The United States and Israel possess unmatched capabilities in intelligence, cyber operations, satellite surveillance, and precision strike. Carrier-based aircraft, submarines, and long-range missiles offer the ability to hit multiple targets across Iranian territory within hours. Analysts often point to the vulnerability of fixed installations—nuclear enrichment sites, command centers, and air defense systems—to such a coordinated assault. The possibility of decapitating strikes against senior leadership, a tactic seen in other conflicts, adds another layer of volatility to the equation.

Iran, for its part, is not without options. Its strategy has long relied on a combination of conventional forces, missile capabilities, and a network of regional allies and proxies across Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen. Any large-scale attack on Iranian soil would almost certainly trigger responses against U.S. bases in the region and against Israel, potentially pulling multiple states into a widening conflict. Even limited engagements could spiral rapidly, driven by miscalculation, domestic political pressures, or the simple momentum of retaliation.

Yet the most complex challenge Iran faces today is not purely military. The protests that have shaken the country since late December represent a profound internal strain. Managing unrest at home while confronting external pressure stretches any state’s capacity. Energy, attention, and resources must be divided between maintaining domestic order and preparing for potential confrontation abroad. This dual-front reality complicates decision-making in Tehran and increases the risk of unintended escalation.

The specter of broader involvement looms as well. China and Russia, both significant players in global energy markets and strategic rivals of the United States, have their own stakes in the stability of the Gulf. Disruptions to Iranian oil exports or regional shipping would affect their economies and their geopolitical calculations. While direct military intervention by these powers may be unlikely, their diplomatic, economic, and possibly covert responses could further complicate an already crowded chessboard.

Beyond strategy and statecraft lies the human cost. The last decades of conflict in the Middle East have produced waves of refugees, shattered cities, and generations marked by trauma. A new, large-scale war involving the United States, Israel, and Iran would not be confined to military targets. It would reverberate through civilian populations, sending millions fleeing across borders and deepening humanitarian crises in countries already struggling with displacement and poverty.

This is why Trump’s offhand phrase—“just in case”—carries such weight. It suggests a readiness to cross a threshold that, once crossed, cannot easily be uncrossed. The movement of an armada is not a symbolic act; it is a material commitment of lives, resources, and global attention. It signals to allies and adversaries alike that the option of force is not theoretical but operational.

Yet there remains another path, one that history shows is harder to sustain but far less costly in the long run. Diplomacy, backed by genuine multilateral engagement rather than unilateral pressure, offers a way to address both Iran’s internal crisis and the region’s broader security dilemmas without lighting the fuse of a wider war. Such an approach requires patience, restraint, and a willingness to accept outcomes that may fall short of maximalist goals.

The world now watches as warships move across the Indian Ocean and protesters continue to fill Iran’s streets. Between these two forces—one internal, one external—lies a fragile moment in which choices made in Washington and Tehran will shape not only their own futures but the stability of the global system. An armada can project power, but it cannot rebuild trust, heal societies, or secure lasting peace.

In the end, the true test of leadership will not be measured by the number of ships deployed or the range of missiles at the ready, but by whether this moment of tension becomes another chapter in a long history of devastation or a turning point toward a more durable, if imperfect, equilibrium. The stakes are not just regional. They are global, and they will be felt in the lives of millions who have no voice in the decisions now being made over the waters of the Gulf.

American News

Trump’s “Board of Peace” or a New Global Order?

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY) :- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : When U.S. President Donald Trump introduced the “Board of Peace,” it was presented not merely as a response to the war in Gaza, but as the foundation of a broader international mechanism for managing conflict and reconstruction across the world. Official charter documents describe a dual mandate: an immediate role in stabilizing Gaza through humanitarian coordination, institutional rebuilding, and transitional security oversight, and a longer-term ambition to evolve into a standing platform capable of engaging future post-conflict environments beyond the Middle East. This framing, reinforced by policy statements and diplomatic briefings, has placed the board at the center of a debate that extends far beyond one devastated territory.

The legal and institutional anchor for the board’s Gaza mission is a United Nations Security Council resolution adopted in November, which welcomed the initiative as a transitional administration through 2027. That resolution authorized the deployment of a temporary International Stabilization Force, required regular reporting to the Council, and framed the board’s role as preparatory to the return of authority to a reformed Palestinian administration. Yet the board’s own charter language leaves open the possibility of expansion into other conflicts, effectively positioning Gaza as the first test case for a wider experiment in global peace governance.

The structure of the board reflects this ambition. The U.S. president serves as the inaugural chair, supported by a founding Executive Board and a professional secretariat responsible for policy coordination and field operations. Membership is divided into two categories. Ordinary members are appointed for renewable three-year terms and are expected to contribute diplomatic, technical, and administrative expertise to the board’s active missions. Permanent members, by contrast, secure an open-ended seat by making a substantial financial contribution, reported as up to one billion dollars, to support the institution’s long-term activities. In return, they gain a role in shaping leadership selection, budget priorities, procedural rules, and decisions about whether and where the board will operate in the future.

Supporters of this design argue that it addresses a chronic weakness in international peace efforts: the lack of predictable funding and sustained political attention. Large, upfront contributions are intended to guarantee the continuity of a professional secretariat, enable rapid deployment in emerging crises, and reduce reliance on voluntary pledges that can be delayed or withdrawn as domestic politics shift. Permanent members, having invested heavily, are expected to remain engaged over the long term, providing oversight and strategic direction.

Critics, however, see a fundamental problem in tying influence to financial capacity. From a justice-based perspective, peace is not a commodity to be purchased. The most meaningful contributions, they argue, come in the form of political risk, diplomatic labor, and technical expertise, not just capital. Governments that mediate between hostile parties, deploy engineers and administrators to fragile environments, or absorb domestic backlash for controversial peace initiatives bear costs that are not measured in dollars. To ask them to pay for the privilege of participation appears to invert the moral logic of postwar reconstruction.

An alternative vision has emerged in response: a global reconstruction fund that separates financial contributions from governance. Under this model, governments, development banks, private institutions, and civil society would contribute according to their capacity, while decision-making would be based on expertise, neutrality, and regional legitimacy rather than financial thresholds. Advocates argue that this approach broadens the funding base, enhances moral authority, and reduces perceptions of exclusivity. The tradeoff is predictability. Voluntary funds are vulnerable to donor fatigue and political conditions, and without guaranteed capital, reconstruction efforts can stall and accountability can become diffuse.

Participation in the board has been broad but uneven. Official briefings indicate that roughly 35 of the approximately 50 invited governments have committed so far. The list includes Middle Eastern states such as Israel, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Jordan, Qatar, and Egypt; NATO members Turkey and Hungary; and countries across multiple regions, including Morocco, Pakistan, Indonesia, Kosovo, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Paraguay, Vietnam, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. Belarus’s acceptance has drawn particular attention, given its strained relations with Western governments and its political alignment with Moscow.

Several close U.S. allies have declined or hesitated. Norway and Sweden have refused. France has indicated it will not participate, citing constitutional and institutional concerns. Canada has agreed in principle but is seeking clarification. Britain, Germany, and Japan have not taken definitive public positions. Ukraine has acknowledged the invitation while expressing unease about sharing a forum with Russia. Russia and China, both permanent members of the UN Security Council, have not committed, reflecting caution toward initiatives that could be seen as diluting the UN’s central role in global conflict resolution.

For the states that have joined, participation carries implications at home and abroad. In Israel, the prospect of a multilateral board shaping Gaza’s transition and potentially influencing security arrangements has sparked intense political debate. Some lawmakers and coalition partners view external oversight as a constraint on Israel’s freedom of action, particularly on sensitive issues such as border control and any future discussion of disarming Hamas. Others see international involvement as a way to share responsibility for Gaza’s future rather than leaving Israel isolated with the burden of governance and reconstruction.

In Iran, the board is widely interpreted through the lens of strategic rivalry with Washington. Political figures and media outlets have portrayed it as an extension of U.S. influence rather than a neutral peace mechanism, warning that participation by regional states could be read as endorsement of an American-led security architecture. This perception matters for governments in the Gulf and beyond that must balance relations with both Washington and Tehran.

One of the most sensitive issues surrounding the board’s Gaza mandate is the question of disarmament, particularly with regard to Hamas. Official frameworks emphasize stabilization and the return of governance to a reformed Palestinian authority, but they are less explicit about how armed groups would be neutralized. The reality that even the combined military and intelligence capabilities of the United States and Israel have not eliminated Hamas’s operational capacity has fueled skepticism that a multilateral board, however well-funded, could succeed where sustained kinetic campaigns have not. For member states, association with any enforcement or inspection role carries the risk of domestic backlash and regional pressure.

All of this unfolds against the backdrop of a multipolar international system. China’s emphasis on non-interference and development-led stability, the European Union’s focus on legal norms and humanitarian standards, the Global South’s sensitivity to perceived Western dominance, and the United States’ strategic framing of diplomacy shape how the board is perceived. An institution seen as aligned with a single worldview risks becoming a coalition forum rather than a neutral mediator. States that feel excluded or marginalized can respond by strengthening parallel mechanisms, from regional organizations to alternative development banks, producing a fragmented peace architecture rather than a unified one.

Formally, the Board of Peace does not replace the United Nations. It lacks treaty-based authority to issue binding resolutions or to authorize force beyond what the Security Council permits. Its influence is practical rather than juridical, flowing from its ability to coordinate funds, support transitional administrations, and shape policy frameworks through diplomacy and expertise. Yet practical influence can shift the balance of global governance if major donors and diplomatic energy flow through a selective forum rather than the UN’s universal framework. The tension is between efficiency and legitimacy, between the speed of smaller, well-funded bodies and the broad acceptance conferred by universal institutions.

Whether the board will collapse or endure is likely to depend on how it navigates this tension. Without sustained participation from all major power centers, it may find its role narrowed to technical coordination and reconstruction rather than political settlement in the world’s most contentious conflicts. A hybrid approach, pairing a transparent, multi-donor reconstruction fund with a rotating and inclusive governance structure while recognizing major contributors without granting permanent political control, offers a possible path toward balance.

The Board of Peace now stands as a test of how global governance adapts to a changing balance of power. Its legacy will not be measured only by what it achieves in Gaza, but by whether it can persuade a divided world that peace can be pursued with both effectiveness and legitimacy, rooted in cooperation rather than ownership, and in shared authority rather than exclusive influence.

American News

Trump’s Bid for Greenland at Davos

Paris (Imran Y. CHOUDHRY) :- Former Press Secretary to the President, Former Press Minister to the Embassy of Pakistan to France, Former MD, SRBC Mr. Qamar Bashir analysis : Davos, the frostbitten alpine enclave carved into Switzerland’s high mountains, has long been more than a resort town. Each winter, it becomes a political and economic marketplace where presidents, CEOs, scholars, and strategists trade contracts, alliances, and narratives of power. Temperatures plunge far below freezing, yet inside the halls of the World Economic Forum, the climate of international relations often burns far hotter than the Alpine air outside.

This year, the world’s attention did not rest on climate pledges or investment forecasts. It centered on the arrival of U.S. President Donald Trump, whose speech was anticipated less as an economic update and more as a declaration of how Washington now intends to shape the global order.

Trump opened with triumph. He portrayed the United States as an economy in resurgence—investment surging, jobs expanding, inflation easing, and industrial capacity returning home. These claims are broadly aligned with recent U.S. data showing strong capital inflows into technology, defense, and energy sectors, alongside continued labor market resilience. But the applause quickly faded as Trump pivoted from domestic success to global power.

The real tremor came not from his economic optimism, but from his vision of security. At the center of his message stood Greenland.

For years, analysts speculated that American interest in Greenland stemmed from two forces reshaping the Arctic: the opening of polar shipping lanes as ice melts, and the presence of rare earth minerals essential for modern technologies. In Davos, Trump dismissed both assumptions outright. He made it clear, in unusually direct terms, that he neither needs Greenland’s minerals nor seeks control over emerging Arctic sea routes.

Instead, he framed Greenland as a cornerstone of what he described as a continental missile defense shield—“Golden Dome” over the Western Hemisphere. In his telling, the United States is building a layered system designed to detect, track, and intercept missiles from any direction, and Greenland’s geography, he argued, is indispensable to making that shield effective. Without Greenland, he suggested, the system would be incomplete—not only for the United States, but for Canada as well.

The message was stark: this was not about commerce or resources. It was about transforming the Arctic into a forward platform for hemispheric security. That declaration sent a ripple through European and North American delegations.

Denmark’s government has long and consistently rejected any notion of transferring Greenland. Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen has publicly called the idea “absurd,” emphasizing that Greenland is not an object of transaction but a self-governing territory whose future lies in the hands of its people. Greenland’s own leadership has echoed this position, welcoming cooperation and investment, but insisting that sovereignty is non-negotiable.

French President Emmanuel Macron has framed the Arctic question as part of a wider European responsibility. He has warned against turning the polar region into a theater of militarization and great-power rivalry, arguing that Europe must defend both its territory and its principles through collective security, not through the logic of dominance.

Germany’s chancellor has taken a similar stance, stressing that the stability of the international system depends on respect for borders, multilateral institutions, and the rule-based order that emerged from the wreckage of the twentieth century. Berlin’s Arctic policy, like much of Europe’s, emphasizes environmental protection, scientific cooperation, and governance through international frameworks rather than unilateral security architecture.

Canada, placed directly under Trump’s proposed “dome,” found itself in an especially delicate position. Ottawa has repeatedly affirmed that Arctic defense must be managed through NATO, NORAD, and international law, not through territorial realignment. Canadian officials have consistently stated that security in the North is a shared responsibility among circumpolar nations, not a justification for redrawing sovereignty.

Even Russia, often cast as the primary strategic rival in the polar north, has responded with measured caution. While Moscow continues to expand its Arctic military and infrastructure footprint, its official statements warn against turning the region into a flashpoint for confrontation, arguing instead for stability through treaties and regional cooperation.

Trump’s response to this resistance was neither conciliatory nor ambiguous. He described American military power in sweeping terms, emphasizing precision, reach, and technological dominance. He portrayed the U.S. defense system as unmatched—capable of neutralizing adversaries’ air defenses, striking targets across continents, and shaping the battlefield before rivals can respond. The tone was not diplomatic. It was declarative.

Security, in this vision, does not flow from international law or collective institutions. It flows from capability. His criticism extended to the very architecture of global governance. He questioned the effectiveness of the United Nations, arguing that it has failed to prevent wars or enforce peace, and suggested that Washington would increasingly disengage from international bodies that do not align with U.S. strategic priorities. This echoed earlier American withdrawals from multilateral agreements and institutions, reinforcing the image of a superpower stepping away from the system it once helped build.

Inside Davos, the contrast could not have been sharper. European leaders spoke of interdependence, shared security, and the dangers of a world governed by raw power rather than negotiated norms. Policy analysts warned that transforming sovereignty into a strategic variable—something to be adjusted for defense planning—could unravel decades of diplomatic precedent.

Beyond the speeches and symbolism, the implications run deep.If security becomes transactional—granted in exchange for alignment rather than guaranteed by law—then smaller and middle powers face a narrowing set of choices. They can align themselves with a dominant power’s strategic architecture, or they can seek protection through alternative coalitions, regional defense pacts, and diversified economic networks.

This shift is already visible. Countries across Europe, Asia, and the Global South are exploring ways to reduce reliance on single markets, single currencies, and single security patrons. New trade corridors, regional financial arrangements, and defense dialogues reflect a world quietly preparing for a future where power is more fragmented and competition more explicit.

Trump’s Davos address suggested that the post–Cold War era of institutional globalism may be giving way to a new age of fortified blocs—where defense systems, trade networks, and political alliances align along hard lines of strategic interest rather than shared ideals.

The world now stands at a crossroads. One path leads toward renewed commitment to multilateralism, where power is constrained by law and cooperation tempers rivalry. The other points toward a landscape of competing spheres of influence, where technological dominance and military reach define who sets the terms of global order.

Davos, once a forum for consensus, has become a stage for confrontation. And as snow continues to fall on the Alpine peaks, the chill spreading across international relations may prove far more enduring than the winter cold. The question now confronting the world is no longer whether a new order is emerging—but whether it will be shaped by dialogue, or by the silent geometry of missile shields drawn across the sky.

-

Europe News11 months ago

Europe News11 months agoChaos and unproven theories surround Tates’ release from Romania

-

American News11 months ago

American News11 months agoTrump Expels Zelensky from the White House

-

American News11 months ago

American News11 months agoTrump expands exemptions from Canada and Mexico tariffs

-

American News11 months ago

American News11 months agoZelensky bruised but upbeat after diplomatic whirlwind

-

Art & Culture11 months ago

Art & Culture11 months agoThe Indian film showing the bride’s ‘humiliation’ in arranged marriage

-

Art & Culture11 months ago

Art & Culture11 months agoInternational Agriculture Exhibition held in Paris

-

Pakistan News7 months ago

Pakistan News7 months agoComprehensive Analysis Report-The Faranian National Conference on Maritime Affairs-By Kashif Firaz Ahmed

-

Politics11 months ago

Politics11 months agoUS cuts send South Africa’s HIV treatment ‘off a cliff’